12 Elements of the Traditional Japanese Home

http://decor-ideas.org 08/18/2015 02:13 Decor Ideas

Japanese homes tend to be small and situated close to one another, whether in urban or rural settings. Yet key features of traditional Japanese residential design ensure privacy, natural light, protection from the elements and contact with the outdoors — no matter the size of the house or its location.

Although most urban Japanese can’t afford single-family homes, their apartments often contain these traditional features, such as soaking tubs and step-up entryways. And many Western-style homes in Japan contain a single Japanese-style room with a tatami floor. Elements of traditional Japanese house design, long an inspiration for Western architects, can be found throughout the world. Here are the essential concepts.

1. Gated entries. Because most residential streets in Japan lack sidewalks, the delineation between public and private space begins at a property’s gate. This traditional roofed gate in Kyoto separates the street from a hidden residence. An old cherry tree hints at an impressive garden inside the walls.

Photo by Hope Anderson

2. Walled properties. Privacy from neighboring houses is achieved through walls at the property line. Concrete block is the most common material for the walls, both in cities and villages, but these large houses in Kyoto boast stone walls topped with wooden fences.

Photo by Hope Anderson

3. Tiled roofs with broad eaves. Japan is a rainy country, and its roofs are designed to drain large amounts of water away from the house. The eaves allow residents to open exterior sliding doors (amado) for ventilation without letting in the rain. This two-story house in the Aoyama district of Tokyo sits on an atypically large lot for the city center.

Photo by Hope Anderson

4. Optimal siting. Japanese houses are sited north-south, with the main rooms facing south, to ensure steady sunlight throughout the day. Views — ideally of mountains or water but more often of a garden — are essential. Natural light is considered a human right in Japan for homeowners and apartment dwellers alike.

5. Step-up entryways. A transitional space between outdoors and in, the genkan is where one exchanges outdoor shoes for slippers, which are worn to protect tatami floors. Genkan hold shoe cupboards as well as decorative objects such as ceramics, flowers or art. They may include or face the tokonoma (alcove), where scrolls and other artwork, as well as ikebana (traditional flower arrangements), are displayed.

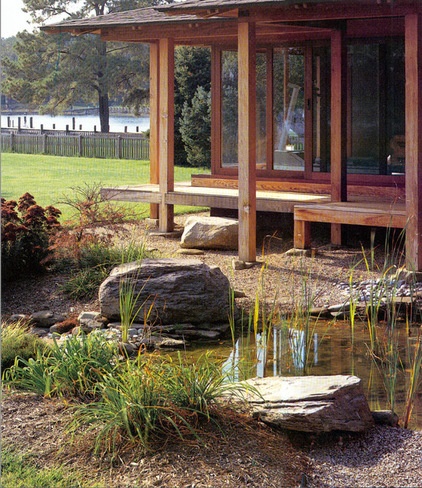

6. Exterior hallways. In addition to connecting rooms, these broad hallways known as engawa are the transition point between indoors and out. In warmer months, they function as verandas; year-round they let in light and air.

7. Sliding doors. These louvered doors and plaster slitted windows (mushiko mado) are particular to Kyoto machiya (traditional live-work homes), but all traditional Japanese houses have sliding outer doors (amado) as well as inner dividers (shoji) that let in light and air while providing privacy.

8. Reverence for wood. The wood in Japanese houses is often stained but never painted, since paint would cover the highly prized grain. Entire tree trunks may be used as roof beams, while the most expensive piece, often an unplaned length of Japanese cypress, is reserved for the tokonoma.

9. Straw matting. Tatami flooring, made from woven igusa (a type of grass), is cool in summer and warm in winter. Though costly, it lasts for years because shoes are never worn indoors. Mats come in standard rectangles whose edges are bound in black cloth or, in the case of wealthy households, brocade.

10. Multipurpose rooms. Because the traditional bedding (futon) is folded and stored in closets during the day, a single large room may be used for sitting, dining and sleeping. Flexible space and movable furniture enable small houses to comfortably accommodate families.

11. Traditional baths. In the past, many Japanese bathed in neighborhood public baths, as only relatively wealthy families could afford the expense of maintaining a furo, which requires not only space but enough fuel to maintain a water temperature of 100 to 108 degrees Fahrenheit (37.8 to 42.2 Celsius). Although public baths still exist, the majority of Japanese homes have their own furo, which is used only for soaking. (All soaping and rinsing takes place outside the tub using handheld showers or buckets.) Bathing remains an essential daily ritual in Japan.

12. Minimal transitions between indoors and out. Access to the outdoors — a concept aided by easily opened sliding doors and windows — is paramount in Japanese design. This indoor-outdoor aesthetic greatly influenced modernist architects in California and around the world. In this photo of the traditional teahouse at the Nezu Museum in Tokyo, only a narrow stone walkway under the eaves separates the house from the majestic and expansive garden.

Photo by Hope Anderson

More

4 Japanese Homes Proudly Speak to Their Surroundings

Design Workshop: How the Japanese Porch Makes a Home Feel Larger

Related Articles Recommended