How Tupperware’s Inventor Left a Legacy That’s Anything but Airtight

http://decor-ideas.org 07/29/2015 00:13 Decor Ideas

Some of the pencil sketches that fill the yellowed pages of a notebook hidden at the National Museum of American History depict inventions that one might assume are jokes. There’s a fish-propelled boat, which envisions a large fish harnessed to the underside of a vessel, moving it forward. There’s a no-drip ice cream cone with a gutter that lets melted ice cream drain back into the bottom of the cone. There’s a comb shaped like a dagger.

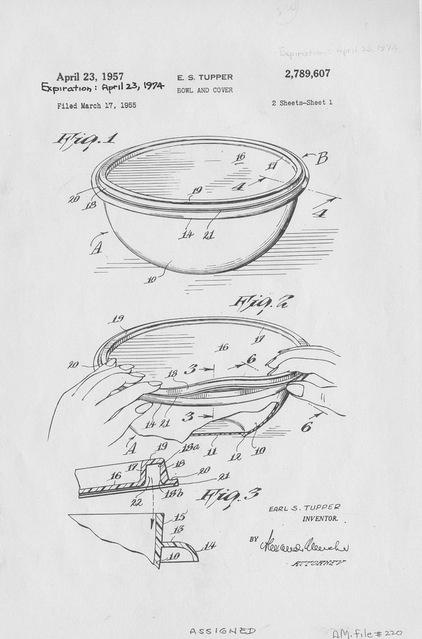

The sketches belong to Earl S. Tupper, born July 28, 1907. While almost none of these concepts lived beyond the pages of his notebook, his late-1940s invention of a plastic food container with an airtight seal did. The Wonderbowl, made by his nascent Tupper Plastics company and later referred to as Tupperware, changed how people store food and how products are marketed. In fact, the products became so popular that today, the word Tupperware is commonly used to describe any plastic food container, taking on that rare eponym status, like Kleenex for facial tissue and Jacuzzi for hot tub.

But Tupper’s success is a rags-to-riches tale full of strangeness. The time from when he began his plastic empire to the time he sold his company for millions lasted less than 10 years, and during that time he took on an almost Howard Hughesian persona that some say was fraught with obsessive ambition, government paranoia and corporate belligerence.

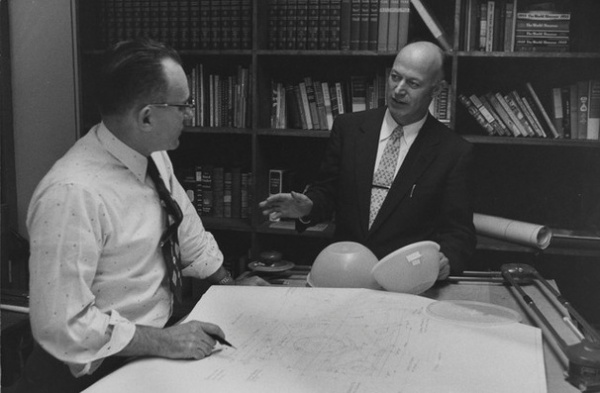

Hollywood Takes Note

In his 2008 book, Tupperware Unsealed: Brownie Wise, Earl Tupper, and the Home Party Pioneers, news reporter Bob Kealing of WESH 2 in Orlando, Florida, chronicled the ups and downs of Tupper and his marketing guru, Brownie Wise (both shown here), whose lively home party sales in the 1950s revolutionized the product marketing business and made Tupper’s company hundreds of millions of dollars. (A retro advertisement for Tupperware products is shown above.)

But just when the company was riding high on soaring profits and Wise was enjoying celebrity status — she was the first woman featured on the cover of BusinessWeek — Tupper abruptly fired Wise, sold the company less than a year later, bought an island in Costa Rica, renounced his U.S. citizenship and all but disappeared.

The story grabbed the attention of Hollywood, and Sony Pictures bought the rights to Kealing’s book last year and is currently in production on a movie. Academy Award-winning actress Sandra Bullock (The Blind Side; Gravity) has signed on to play Wise, and Tate Taylor (The Help) is set to direct. Kealing is also working on a new edition of the book, with new revelations, slated to be released next year. “I knew the story would be so compelling,” Kealing says. “I can’t say I was totally surprised when Hollywood took note.”

Recipe for Success

Tupper grew up on farms in Massachusetts. His mother, Lulu, made money by doing laundry for people and taking in boarders. His father, Ernest, ran the farm, albeit poorly and without much ambition, according to a PBS American Experience biography on Tupper.

But Tupper was the opposite of his father. At age 10, he began selling the family’s produce door to door. In his teens, he began scribbling inventions in his notebooks. He came up with the fish-boat idea at age 19. He had no luck selling his inventions.

In 1931 he married Marie Whitcomb — they would go on to have five children — and he opened a landscaping business called Tupper Tree Doctors, which was forced into bankruptcy during the Depression in the 1930s, according to the PBS series.

His fortune turned when he landed a job at a plastics factory in Leominster, Massachusetts. There he spent a year learning the ropes before buying some used molding machines and starting his own plastic products company, called Tupper Plastics, whose early containers for soap and cigarettes basically flopped.

“But Tupper was someone who dusted himself off from failure and decided early on it was up to him to make it in life,” Kealing says.

The Wonderbowl Arrives

After World War II, Tupper got his hands on a block of polyethylene, a “worthless, smelly slag product,” Kealing says, that he experimented with for months before finally turning it into a moldable, aesthetically pleasing plastic product that didn’t smell. He used the poly-T, as he called it, to create his first Tupperware bowls. “It was the kind of plastic product America had never seen before,” Kealing says.

At the time, Kealing says, people were putting their leftover dinners into bowls and covering them with shower caps. “It wasn’t even airtight,” he says. Tupper’s new Wonderbowls were. Pushing down on the plastic lid forced the air out of the container, creating a vacuum seal — an idea based on paint can lids. His Tupperware made it into department stores, won design awards and was marketed heavily. But sales were poor.

The Rise of Brownie Wise

It turned out, people didn’t know how to use Tupper’s wares, and the vacuum seal lid was difficult to explain and promote through advertising and packaging alone. Enter Brownie Wise. At the time, she was using sales parties to sell Stanley Home Products’ cleaning supplies to small groups of women at private homes. Wise had ordered some Tupperware and discovered that all those housewives were enamored with the plastic food storage containers.

Tupper noticed that Wise was placing huge orders for his Tupperware products, and recruited her to Florida in 1950 to helm a similar house-party sales method. It was so successful that Tupper pulled Tupperware from store shelves and focused solely on the party approach. “It was social networking before it was cool,” Kealing says. The move paid off, and soon the company was raking in money and Wise, seen here at a Tupperware party tossing a water-filled bowl, was ascending to iconic status. But her celebrity would end up being her downfall.

End of an Era

While Wise, seen here at a home party in Hawaii, basked in the glow of publicity, Tupper seemed to retreat farther into the shadows. “This is a guy who had an apartment built into his office in case the bomb was dropped,” Kealing says.

Tupper feared his fortune was at stake because of government taxation. And after running his company for less than a decade, he abruptly decided to sell it. But not before knocking Wise off her pedestal. “He thought the company would be a lot more attractive to buyers if it wasn’t run by a woman,” Kealing says. “He felt Wise got too big for her breeches, taking her eye off the ball by focusing on herself rather than the product.”

By 1958, Tupper and Wise’s relationship had grown toxic. One piece of correspondence that Kealing uncovered shows that when Tupper offered a bit of advice to Wise, she responded: “Your advice is about as welcome as a first class case of leprosy.”

Tupper fired Wise that year, leaving her without stock options. “That’s a unique moment in history that showed how swift and firm he could pull the rug out,” Kealing says. “Brownie walked away with a $30,000 settlement to drop a lawsuit against the company, and that was that. Then Tupper actively wanted to write her out of company history, and was pretty successful. “Executives after her tried to bury her legacy, even going so far as digging a hole on the Tupperware corporation property and dumping copies of Wise’s self-help book, Best Wishes, into it. That’s cold.”

Wise failed to regain the success of her Tupperware days. She became an accomplished potter, even winning several awards, Kealing says. According to her obituary in the Orlando Sentinel, she “grew reclusive in her later years.” Wise died in 1992 at the age of 79.

The Sale of Tupperware

Tupper sold his company less than a year later to Rexall Drug for $16 million (around $130 million in today’s money), renounced his U.S. citizenship so he wouldn’t have to pay taxes, bought an island in Costa Rica and took his fortune with him. He did become philanthropic, though, and left money to charitable causes after his death in 1983 at the age of 76.

Even in his final years, Tupper’s mind was always working. While researching his book, Kealing spoke with Gary McDonald, a former vice president at Tupper’s company, who recounted many stories about his boss. “For example, before going into heart surgery, Tupper calls McDonald and starts telling him how the heart machine could work better, how he sees condensation building up in there,” Kealing says. “His mind was going a mile a minute even as he was going into surgery.”

Modern Times

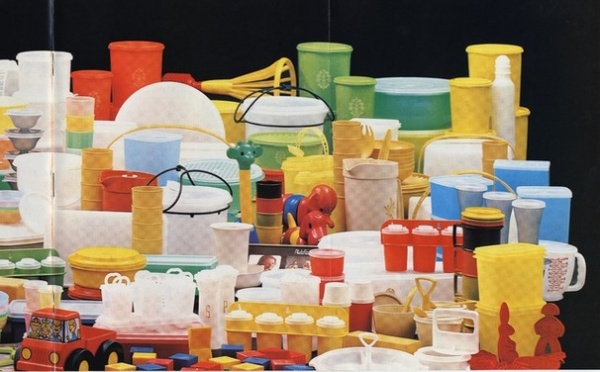

Today, Tupperware and its home parties live on worldwide. (A current photo of its food containers is shown here). The company has moved beyond just food containers to include juicers, electricity-free food processors and sausage makers. Wise’s legacy, meanwhile, has resurfaced and been embraced and widely celebrated. In fact, today Wise gets more attention than Tupper does on the company’s website.

Despite efforts by Tupper to write her out of history, her charisma and contribution to the success of the company couldn’t be scrubbed out so easily. “She was the first ‘Mad Woman’ in an era of ‘Mad Men,’” Kealing says. “This was a revolution driven by women. It wasn’t just Wise. But she centralized the training and perfected the idea and deserves credit. And Tupper deserves credit for leaving the sales to her.”

See sketches of Earl S. Tupper’s early inventions

Related Articles Recommended