Must-Know Furniture: The Mora Clock

http://decor-ideas.org 05/31/2015 05:13 Decor Ideas

It’s not every day you hear a clock described as sexy, but Mora clocks are distinctly shapely. With a curvy, hourglass silhouette, Mora clocks are a Swedish-made treasure and the envy of many. If you’ve been thinking of buying one or just have a crush, learn more about the unique design of the majestic Mora.

Like a lot of endeavors, the Mora clock was born from creative energies unleashed during hard times. In the mid-1700s, when the agriculture and mining industries were foundering in the town of Mora, in Sweden’s central Dalarna region, many townspeople took up clock making to ease their hardscrabble lives. Different families began specializing in particular parts. Some made faces, while others fabricated cases, and others focused on painting.

It is said that by 1800, the Mora clock’s golden age, about 100 families were involved in the town’s timely enterprise. As with most cottage-industry wares, each Mora clock was individually crafted. “No two clocks are ever the same, and that is part of their allure,” says Jo Lee of U.K.-based Swedish Interior Design, a leading expert and dealer of Mora clocks.

With their freshly scrubbed appearance and fanciful shape, what’s not to like?

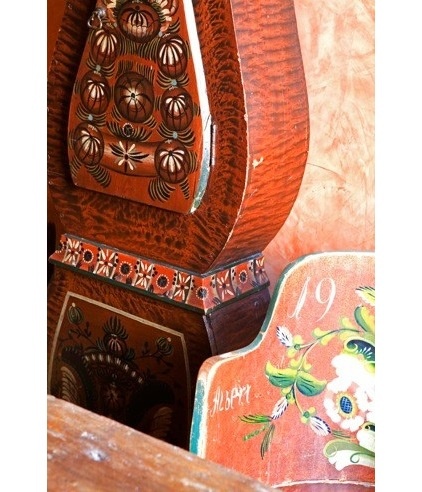

Mora clocks were made for local people — an everyman’s clock for rich and poor alike. However, the complexity of the carving, shape and finish varied greatly depending on the client’s means. Many of the clocks, which were produced through the late 19th century, were given as wedding presents. And as with the 1836 example shown here, the year was often painted on the clock as a decorative commemoration.

Shapes and sizes. “Mora clocks come in all shapes and sizes, a bit like people, and each one has its own personality, which is what makes them unique,” Lee says. While there are varying styles of Mora clocks, their differentiation lies mostly in how the surface of the clock is treated.

Swedish antiques expert Paulette Peden notes on the Antiques Council’s website that clocks from the north of Sweden tend to be taller and thinner, while those from the southern regions have wider tummies and more exaggerated curves.

Although generally quite tall, Mora clocks fit well in tighter spaces, as they tend to be shallower than their English counterparts. Mora clocks are generally 71 to 99 inches (180.3 to 251.4 centimeters) tall, 8 to 12 inches (20.3 to 30.4 centimeters) deep and 20 to 28 inches (50.8 to 71.1 centimeters) wide.

Hoods and faces. While likely self-explanatory, the clock face is the flat disc that shows the time. Lee says the face usually measures about 19 inches (48.2 centimeters) in diameter and is made out of hammered metal coated in white enamel. Numbers, minute markers and sometimes decorative elements were painted on in black paint. Standard Arabic numerals were most common, although rarer Roman numerals were also used. Lee notes that it’s typical to find that enamel has flaked off over time in places, but feels that this enhances the beauty. However, she says that touching up paint on the face was also a common practice, especially before passing the clock on to another generation.

The hood is the bentwood bonnet that surrounds the face. Often it has ornamentation on top, like the spikes seen in this image, or just revels in its simplicity. Other decorations include carvings, crowns, scroll details and urns.

Clocks for affluent clients tended to have an expensive blown-glass hood cover added to protect the face. The glass is usually contained in a hinged ring within the hood, but occasionally was set directly into the hood. Lee points out that you can tell the original antique glass by the bubbles and inconsistencies in it, and that it adds value to the piece. Often the glass hood was also paired with a convex glass cover over the clock’s belly door, with a surrounding decorative molding. Meanwhile, the faces and belly doors for simpler clocks were left unprotected. So it’s common to see both bare and glassed-in models.

Finishes. Perhaps most famous are the Mora clock’s handsome finishes. While not the only treatment, the most common is a simple flat paint. Whites and pale grays and blues are especially prevalent. Gilded details sometimes adorn the clocks to reflect the light and brighten bleak winter days.

Today we sometimes find Mora clocks with a scraped finish, as shown here. Lee says that many dealers will claim that the clock was scraped back to its original paint. “This is really not the case, as the clocks would not have looked like that when originally painted,” she says. “It’s just a special effects finish that has become popular and provides no particular value to the clock, other than a visual effect.”

The finishes on Mora clocks were periodically refreshed. Like the faces, when the clock was passed from one generation to the next, the Swedes took to the brush and applied a fresh coat of paint. You’ll often see stenciled or pencil notations inside the clock bodies giving dates when the clock was repainted or refurbished.

Some Mora clocks have hand-painted figural folk art designs called kurbits or jamtland. Brightly painted, they have a more rustic, country appearance, like in the image shown here.

Meanwhile, other Mora clocks have a trompe l’oeil finish mixed with gilded accents. Unlike the folk art clocks, these Moras were made for well-to-do clients living in the city, and are sometimes referred to as city-style Mora clocks.

It’s more unusual, Lee notes, to find a Mora clock with a natural wood stain finish, like this example. “This gives them a different feel and allows them to fit perfectly into darker, more woody settings,” she adds.

Mechanisms. One of the stark differences between Mora clocks and their English grandfather clock counterparts is that the Mora has an enchantingly light crystalline chime made by one or two bells in lieu of a deep, resounding dong. It also has more frequent five- to seven-day movements before it needs to be rewound.

Mora clocks have very sensitive mechanisms. The kicker is that they have to be perfectly level, otherwise the swing plane of the pendulum will be affected. Because the clocks were often housed in old homes with sloping floors, many of the clocks have holes in the back of the case where they were braced to a wall for stability. In addition to the level sensitivity, their inner workings are especially susceptible to changes in temperature and humidity.

Old-school or battery powered? Because of the sensitivity challenges and the fact that most clock repairers, especially in the U.S., aren’t familiar with the Mora, a lot of folks opt to fit their clock with a modern electric battery mechanism. Lee says that the old mechanism can be easily removed and needs to be carefully stored. Because the switchover isn’t permanent, it doesn’t damage or devalue the clock.

If you don’t want to maintain the original pendulum system, Lee says there are two choices: a battery-driven mechanism with no chime, or a battery-powered one with a small speaker that plays a recorded chime. “It sounds exactly like the real thing, except you can have a night-off switch that you don’t [have] on a real mechanism,” she says.

Cost. Like any antique, vintage antique Mora clocks vary in price. At Swedish Interior Design, Lee’s fetch between $1,600 and $12,500 (about 1,000 to 8,000 pounds), depending on the condition, shape and provenance. While not the focus of this article, new but simple reproductions can be found in the $800 range.

While cost is certainly a factor, what’s most important when selecting a Mora is something far more mystical — finding that special bond. “There will be one that jumps out at you emotionally. It will have that indefinable something special that calls to you,” Lee says.

More: The Grandfather Clock

Related Articles Recommended