Houzz Tour: Passive House in Vermont Slashes Heating Bills

No muss, no fuss and no fossil fuels required were the main qualities this couple sought for their weekend and eventual full-time home. During a three-year search for a house in central Vermont, they knew they weren’t up for the maintenance and remodeling the antique houses on the market would have required. One of the homeowners is an engineer who builds factories and puts in pipes, pumps, boilers and wires all day. He wanted a house without all the complexity of so many parts and pieces that always need to be fixed and maintained. So they researched passive house construction, found an abandoned farm with a house dilapidated beyond repair on site, worked with a team of experts and built a new home that is certified by Passive House Initiative U.S., or PHIUS. Now taking care of and heating the home is simple and easy, just as the couple dreamed it would be.

Learn more about passive houses: The Passive House: What It Is and Why You Should Care

Photos by Eric Roth Photography

Houzz at a Glance

Who lives here: This is the weekend home of a couple with two kids; the youngest is getting ready to start college. It will be their full-time home after they retire.

Location: Central Vermont

Size: 2,700 square feet (251 square meters); 3 bedrooms, 2.5 bathrooms

“Passive house is a certification that is the most stringent in the world. It means a house is super-insulated, with airtight construction, high R-values and very strong thermal performance from windows and doors,” says Jordan Goldman of ZeroEnergy Design, who served as the passive-house consultant and mechanical designer on the project. “This home uses approximately 90 percent less energy for heat and at least 60 to 70 percent less energy overall than a code-built home.”

The two most crucial elements of designing a passive house are orienting it to take full advantage of the low winter sun and creating a tight envelope. This side of the house faces directly south, which allows the sun to warm the home through the large windows and doors. In the summer when the sun is higher, the overhangs and balconies shade these openings to help keep things cool.

The two flat-plate solar thermal panels on the roof heat the water. The panels usually keep the water at 140 degrees, but the homeowner notes that even if there is an unusual span of cloudy days, the water temperature drops to only about 100 degrees. They have a small backup electric system to heat the water in case this happens. Because of the way the panels warm up, snow melts off them.

Let’s Clear Up Some Confusion About Solar Panels

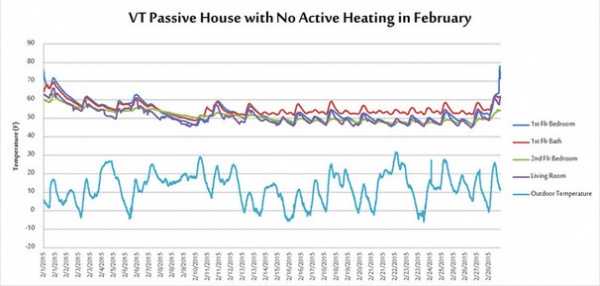

The harsh winter of 2014-15 was only the second winter the couple spent time here, and it really put the house to the test. This graph shows the average temperature outside (in blue) compared with the temperature maintained inside the house in February 2015.

Because the couple mostly uses the house on the weekends, it usually cools down to about 50 degrees Fahrenheit while they are away because the wood stove is not in use. After they throw a few logs on the fire, it’s about 60 to 62 degrees by the time they go to bed, one of the homeowners says, and by morning, it’s 68 to 70 degrees. When they leave, he sets the backup system to be ready to kick on if the house cools down below 45 degrees, but he says it rarely does; the heat from the sun is usually enough.

Ben Falk of Whole System Design had already completed a master plan for the 102-acre farm before ZeroEnergy Design began designing the house. He also helped them enhance an existing orchard with additional fruit trees. “The house placement was chosen for its relationship to the agricultural uses,” architect Stephanie Horowitz says. She oriented the house to take full advantage of the sun through large windows and doors.

The architects worked with the timber frame construction structures by Bensonwood, a New Hampshire company that manufactures factory-built homes with a focus on sustainable materials and energy-efficient performance. The framing and panels arrive on a flatbed truck and the contractors assemble the house with a crane in a matter of days. “We made a few modifications to their panels that added some rigid insulation to make sure they would meet the strict PHIUS performance standards,” Horowitz says.

The architectural design breaks the house into three sections — the steel-frame around the deck, the one-floor section of the main living space and the two-story bedroom wing beyond it. The steel framing mimics the timber frame structural system of the rest of the home.

The homeowner was familiar with the industrial fiberglass grating he chose for the balcony floors; it is used for industrial platforms in the factories he builds. Its gray color matches the galvanized steel framing used on the exterior.

The main living areas are contained on the left side; the bedrooms are stacked to the right with the master bedroom on the main floor. “Ceiling height is not as valuable in bedrooms,” Horowitz says.

The first-floor master bedroom has the best of both worlds, enjoying the eastern light in the morning and the heat gain from the south-facing openings.

“Durability and resiliency were very important to these homeowners,” Horowitz says. This meant finding low-maintenance materials that could stand up to the elements. The siding is thermally modified poplar that does not need to be stained periodically, the roof is a standing seam metal roof, the deck is ipe, the metal framing is galvanized structural steel and the material around the bottom of the house is Cor-Ten steel.

A covered porch is a lifesaver during inclement weather and keeps the front door from being blocked by snow.

In the entry, a tongue and groove cedar ceiling adds textural interest overhead. A custom cabinet serves as a coat closet. The floors are Vermont ash.

One issue with a tight envelope is keeping the air healthy and fresh. The architects used a heat recovery ventilator (HRV) to provide continuous fresh air in the home while the homeowners are there. While there is no co-mingling of the inside and outside air, when the air comes in from outside, it is preheated or pre-cooled, depending on the season, by exchanging thermal properties with the outgoing air.

“They turn the HRV down very low when they are not there,” Goldman says. “We used nontoxic materials to build the house, which keeps the indoor environmental quality as high as possible.” One such material they used was PolyWhey (made by Vermont Natural Coatings) to finish the wood.

The main living space is open with a vaulted ceiling and enjoys the heat gain from the south-facing windows, which is enhanced by an efficient European wood stove made by Austro Flamm. Heat from the stove spreads throughout this space and into the bedrooms.

The cabinets behind the island were once a showroom display at Poggenpohl, modified to fit the space. The carpenters at Housewright Construction completed the rest of the cabinetry as well as the custom ash staircase. Some of the walls are covered in the same local ash wood used on the floors and staircase as well.

Because the walls are so tight and insulated, they are about three times thicker than a standard wall, which Horowitz kept at the forefront of her mind during the design process. “The scale is so integral to the design,” she says. “The very thick wall system lends itself to larger openings.”

Of course, no matter how efficient the walls are, all is lost if the windows and doors can’t perform. They obtained these high-performance triple-pane windows from Architectural Openings.

Lounge Chair: MR chaise lounge, Knoll

You can really see the thickness of the walls best around the small windows. To be clear, it is not possible to create a 100 percent passive house in a climate like Vermont’s. A small high-efficiency system provides conventional heating with electricity.The bathroom floors have radiant heat to protect the pipes from freezing in winter. However, there is no oil, gas or other fossil fuel providing energy to the house. The homeowner notes that the backup system rarely kicks on.

The ceiling is covered in prefinished maple plywood. The plywood adds a warm decorative touch, and the choice also fit the the spirit of keeping things as easy and simple as possible. “Unlike with drywall, the contractors only had to go up the scaffolding once to install this,” the homeowner says. “They went up, screwed it in, and they were done.”

Dining chairs: Marais A56 armchairs; armchair: Flight recliner in leather

In addition to grabbing all of that heat from the sun, the large openings also open up the living spaces to the bucolic views of the surrounding farmland.

The master bedroom is on the first floor. It enjoys the morning light from the east and the heat gain from the large south-facing windows.

The staircase landing offers a sweeping view of the first floor living spaces. It also gives the best view of the structure of the timber frame construction.

The staircase is ash and was built by Housewright Construction.

In the basement, a passive root cellar uses the Earth to keep food cold. This idea has been around for a long time, which makes one realize that while passive principals utilize the latest cutting-edge technology, they are also based upon building techniques people used for hundreds of years before climate control was readily available.

While Goldman didn’t have exact figures on how much more expensive this particular house was to build to make it passive, he estimates that right now passive house construction costs are about 5% higher than code-built houses. “These costs will go down as more builders become more familiar with passive house construction,” he says. It will also go down as materials that meet the certification standards become more readily available in the United States. At the time the high-performance triple-pane windows for this home were ordered, they had to be fabricated in Europe, but both Horowitz, Goldman and the homeowner noted that a factory recently started producing them in Chicopee, Massachusetts.

Schematic design, mechanical design: Stephanie Horowitz, ZeroEnergy Design

Passive house consultant and mechanical designer: Jordan Goldman

Master plan: Ben Falk, Whole System Design

General contractor: Estes and Gallup

Timber frame and building envelope panels: Bensonwood

Consulting architect: Paul Bilgen

Windows and doors: Architectural Openings

Carpentry and cabinets: Housewright Construction

Browse more homes by style:

Small Homes | Colorful Homes | Eclectic Homes | Modern Homes | Contemporary Homes | Midcentury Homes | Ranch Homes | Traditional Homes | Barn Homes | Townhouses | Apartments | Lofts | Vacation Homes