Houzz Tour: Victorian's Beauty Is More Than Skin Deep

James Wright wasn’t looking for a house to do up; he wanted a plot of land. “I started off wanting to build a house from scratch, as all architects do,” he says. “But after a few years, we realized it was never going to happen in the area where we were looking, so we decided instead to find an existing house and adapt it.”

James’ wife, Tamara, asked local real estate agents and found what eventually would become the family home. “It had a leaky roof; needed rewiring, replumbing and replastering; and it had damp, as with all houses when they get to around 100 years old,” says James. “It needed a lot of attention, which was great — just what I was looking for!” And his vision? “I thought, ‘We can make this house beautiful — but let’s make it energy efficient, too, and let’s make that the driver.’”

Houzz at a Glance

Who lives here: Architect James Wright; his wife, Tamara; and their 3 young children

Location: Hackney borough of east London

Year built: 1893

Size: 5 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms

“Domestic building stock is responsible for around a quarter of all U.K. carbon emissions,” says James, of Macdonald Wright Architects. “Most efforts to reduce the contribution made by people’s homes have focused on new-build housing, but I was keen to prove that a 120-year-old building within a conservation area could be adapted to become as efficient.”

The floors throughout the house are sustainably grown Douglas fir, and the baseboards have an interesting shadow gap. “It gives the impression the floor is like a giant jigsaw piece slotted into the existing plan,” James says.

Flooring: Dinesen

“The idea was to construct a modern, energy-efficient family home behind the existing Victorian facade,” James says. This included demolishing and reconstructing the original house — except the facade — and adding a new roof, walls, floors and underfloor heating throughout. He also added a basement and a loft, as well as numerous ecofriendly details, such as insulation, passive solar heating and a sophisticated greywater recycling system to power the toilets and washing machine and for garden irrigation.

“The house is in a conservation area,” says James, “so we had to do all this work without it showing.” The glass-paneled front door and windows are all painstakingly restored originals.

Greywater recycling system: Pontos Aquacycle, Hansgrohe

The fireplace is one of the few original details they retained. “It’s a terraced house, and the fire breasts are part of the party wall, so I thought they should stay,” James says. A Danish Morso wood-burning stove has been fitted to supplement the underfloor heating. “Morso produces some of the most energy-efficient stoves in the world,” he says.

The large dining table was custom made by Bulthaup, which also made the kitchen. “It’s the perfect height for Hans Wegner’s C24 Wishbone chair,” James says. “I specified the length of the table to ensure that, at a squeeze, we could fit 10 of these chairs around it.”

Pendant lights: Original BTC; chairs: Wishbone

James wanted to create something distinctly modern. “The interiors are a contrast to the claustrophobic, cluttered rooms normally associated with the Victorian house,” he says.

Four-sided steel frames, rather than beams, provide extra structural support, which has allowed James to open up the building. The rear of the house now incorporates a terrace and an open-plan kitchen–dining room, which connects the garden to the existing house.

James chose a palette of natural materials, all of which, along with the fixtures, were either locally sourced or from within the European Union. “Materials include coppiced chestnut fencing from Sussex, Welsh slate, French limestone, Danish timber floorboards, and brass cladding from the U.K.,” he says. “Many of the tradespeople were local, too. It was always comforting during construction to see how few vans — and how many bicycles — arrived each morning.”

The wire horse sculpture seen here is by Debi O’Hehir, one of several of her works in the house. “Tamara has a passion for horses — and I enjoy the expression of their form,” says James.

Sculpture: Debi O’Hehir

The windows are the original 1893 sash units. “The glass is old and so distorts the view through it,” James says. “I like that effect, and we couldn’t have replicated it with newer windows.” Each unit, however, was removed, taken apart and reconstructed with new wood spliced in where required and new ironwork. Weather stripping has improved their thermal performance.

“We don’t have sofas, coffee tables, a TV or those sorts of things,” James says. “We live quite a spartan life. The English oak coffer under the window is 16th century and is used to store the children’s toys. Furniture in the house tends to rotate around the different rooms.”

Wicker floor light: Gervasoni, Darklight Design; armchairs: Carl Hansen CH25, Ferrious

An original Le Corbusier etching hangs over the fireplace. James and Tamara found it in a gallery in Paris on their honeymoon. “It’s my favorite picture in the house,” James says.

Light flows freely throughout the ground floor, thanks to a series of four structural steel frames, which allowed all the original internal walls to be removed.

The walls feature small niches for displaying decorative objects. “All the external walls were heavily insulated to improve the energy rating of the house,” James says. “This meant increasing the thickness of walls internally by more than 150 millimeters [about 6 inches]. In a number of places, I chose to cut out small pockets and form LED light boxes for art displays. We also did this on internal walls where we had space.”

He elaborates that most of the light boxes “were specifically sized to suit artworks we owned, but some are used for a rotating gallery of paintings and clay models by the children.”

The kitchen is a Bulthaup b3 design, which James had made to fit the space. The cabinets and countertop stretch unbroken across 9 meters (about 25½ feet) and are flooded with daylight, thanks to the 6-meter (19½-foot) skylight above.

Appliances: Gaggenau

The simple box form of the kitchen–living area extension clearly defines the new addition from the original building. The exterior of the extension is clad in recycled brass panels treated with blowtorches. “It’s oxidized, which is why it’s that color,” says James.

“I’d seen an architect in Greenwich do the same — Capisco, the firm behind the dome of the planetarium there, in fact,” he adds. “I looked into it and discovered the company was right on my doorstep, and so I got in touch and asked them to take on our much smaller, job, which they did.”

“The open-plan nature of the ground floor really comes alive with people,” says James. “The garden and terrace are treated as rooms, and the connection between house and garden is blurred. When the glass doors are open, the level thresholds allow the children to ride their bicycles from inside to out.”

This dark, glamorous bathroom has been designed as a wet room. Roughly split Cwt-y-Bugail Welsh slate covers the floor and walls. The bath is a reproduction of a late-19th-century French double-ended model.

Tub: Empire, The Water Monopoly; tub faucet: Vola

This child’s bedroom lies in the new addition at the rear of the house.

The master bedroom is part of a suite for James and Tamara. “There’s a bedroom, bathroom, dressing room and space for a desk,” James says. “I wanted to ensure the bedroom could feel very open, but could also be closed off to become more private.”

The unusual-looking door measures 1.8 meters (about 6 feet) wide and was made to James’ design. “The horizontal handrail is actually a joint,” he says. “The door was too large to bring up the stairs and weighs almost 150 kilograms [about 300 pounds].”

He adds, “The lacquers and paints used in the house are by Biofa and contain no volatile organic compounds, so are far more healthy.”

Low-energy wall light: John Cullen Lighting

One of the home’s five bedrooms is used as a library. “The house has a calming sense of simplicity, which helps me feel relaxed after a long day in the studio,” James says.

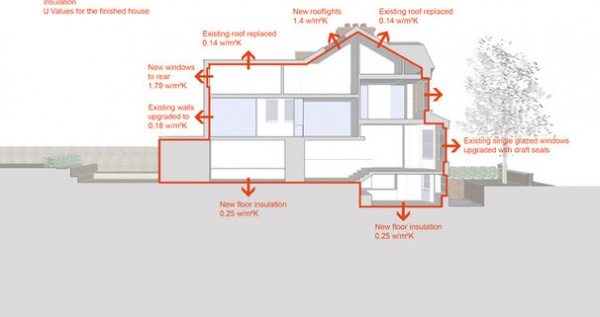

James’ plan for the rebuild of the house.

The house was stripped to its bare bones during the renovation. “Until the house looked like this, I really didn’t know what I was going to do with it, which fitted with my original premise that I was going to build a house from scratch,” James says.

The roof-mounted solar water heating system is by Viessmann. “There are what’s called evacuated tubes on the roof, which take up around 2 square meters [21½ square feet] of space — so it’s not for everyone,” James says. “The sun beats down on them and heats up a metal plate inside. The heat from that goes into the storage tank, which is a bit bigger than a normal hot-water cylinder. The outlay may seem a lot — it was 1,600 British pounds [about $2,400] and then you need a new storage tank as well — but the payback is around seven or eight years. And you can probably get cheaper versions — this one is top of the range.”

Solar collectors: Vitosol 300T, Viessmann

Browse more homes by style:

Small Homes | Colorful Homes | Eclectic Homes | Modern Homes | Contemporary Homes | Midcentury Homes | Ranch Homes | Traditional Homes | Barn Homes | Townhouses | Apartments | Lofts | Vacation Homes