Frei Otto Named 2015 Pritzker Prize Winner a Day After His Death

http://decor-ideas.org 03/11/2015 10:13 Decor Ideas

Architecture fans were hit with a bittersweet punch today after learning that German architect Frei Otto, known for his pioneering use of lightweight tent-like structures, was awarded the 2015 Pritzker Architecture Prize, an announcement that came just one day after his death at the age of 89.

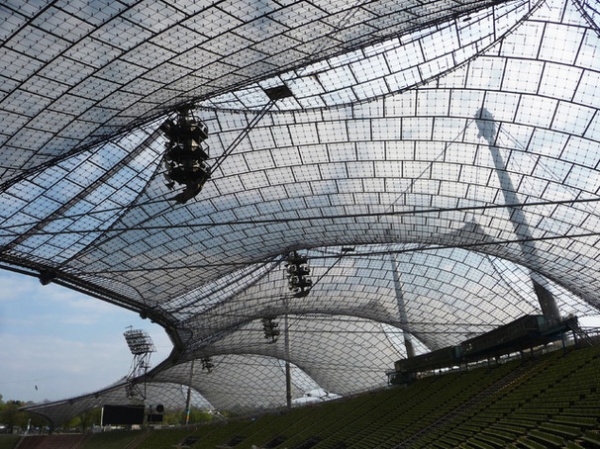

Otto gained fame for his tensile structures that incorporate the use of tension rods and cables to create strong yet incredibly light structures. Perhaps his most famous was his stadium roof canopies for the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich (shown here).

“He has embraced a definition of architect to include researcher, inventor, form-finder, engineer, builder, teacher, collaborator, environmentalist, humanist, and creator of memorable buildings and spaces,” the jury said in its statement.

This is the first time in the Pritzker’s 36-year history that the death of the winner occurred before the announcement could be made. The announcement was slated for March 23 but was abruptly moved up after Otto’s death. The Pritzker Architecture Prize is given by Chicago’s Hyatt Foundation and has long been considered the top award in the field.

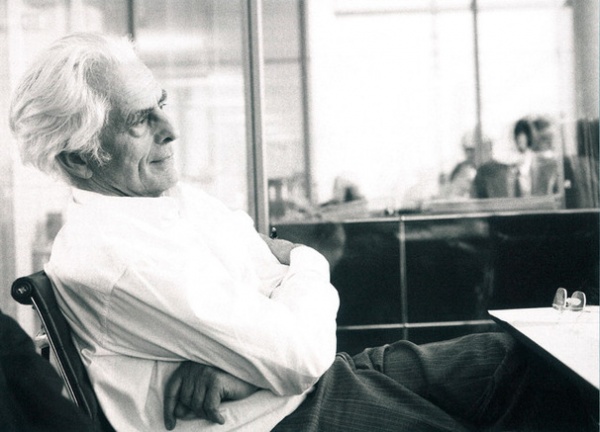

After being called for military service in 1943, Otto (shown here in 2015) became a prisoner of war in France in 1945 and spent two years in a prisoner camp working as a camp architect, learning to build various types of structures using a minimal amount of materials.

The 1967 International and Universal Exposition or Expo ‘67 in Montreal, Canada

Otto went on to become a powerful force in post-World War II architecture, wielding great influence during the 1960s and ‘70s, which has lasted through to today. “Frei Otto represents someone who remained loyal and constant with his beliefs about how architecture can improve the world,” says Carlos Jimenez, a professor of architecture at Rice University in Houston and one of the longest-serving Pritzker jury members. “Renzo Piano, Norman Foster, Richard Rogers and Shigeru Ban owe a lot of gratitude to this man.”

Otto was a world-renowned innovator and made “important advances in the use of air as a structural material and to pneumatic theory, and the development of convertible roofs,” according to a biography released by the jury.

Aviary in the Munich Zoon at Hellabrunn (1979-80)

“Otto’s stuff is much more based in engineering, and structural to the extent to which construction and materials can express lightness and openness,” says Kevin Alter, an architect at Alterstudio and a professor of architecture at the University of Texas.

Institute for Lightweight Structures (1967) at the University of Stuttgart in Vaihingen, Germany

Furthermore, Otto’s early development of computer technology to aid in the development of structural engineering is something that younger architects are drawn to even today. “The young generation of people who think of cutting-edge architecture look to Frei Otto as a genesis of that stuff,” Alter says.

Japan Pavilion, Expo 2000 Hannover (2000) in Hannover Germany, designed with Shigeru Ban

Alter says the Otto selection is a curious choice but “a lovely one.” Otto, who had been practicing for 60 years, worked more behind the scenes in recent years. “From the outside it’s looked like the jurors were trying to identify really accomplished architects having a moment of current influence,” Alter says. “If they are changing course maybe they are directing people to look at architects like Frei Otto again.”

Jimenez, who served as a juror from 2000 to 2011 and helped select winners like Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid, Richard Rogers and others, says the prize is not necessarily about picking current tastes or of-the-moment architects. “What’s important is to acknowledge contributions someone has made to architecture. And that can happen early or in the middle of one’s career. Or it can be about their entire career,” Jimenez says, adding, “It makes the prize ecumenical in my view.”

Jimenez says he and his colleagues, including 2014 Pritzker winner Shigeru Ban, had considered Frei Otto before, even traveling to Munich to view his work, as is customary of the jurors during deliberations.

Diplomatic Club Heart Tent (1980) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

The rules of the prize clearly state that the recipient must be a “living architect/s,” but Jimenez points out that the selection of Otto happened well before his death, and that Otto knew of the prize before his passing Monday.

“I’ve never done anything to gain this prize,” Otto told Pritzker officials, as reported by the New York Times. “Prize-winning is not the goal of my life. I try to help poor people, but what shall I say here, I’m very happy.”

For Jimenez, this isn’t the first time that death has darkened the mood of the prize. He says that in 2003 he and his fellow jurors were deliberating about Geoffrey Bawa, the Sri Lankan architect, but had to remove him from consideration after learning of his death.

Otto will forever be known as an architect who pushed the limits of architectural and engineering expression with a certain modernist zeal, as evident in his own house shown here. “Frei Otto is one of those architects one has to respect for his convictions and ability to remain loyal to his principles and ideas,” Jimenez says.

More: Meet Shigeru Ban, Winner of the 2014 Pritzker Architecture Prize

Related Articles Recommended