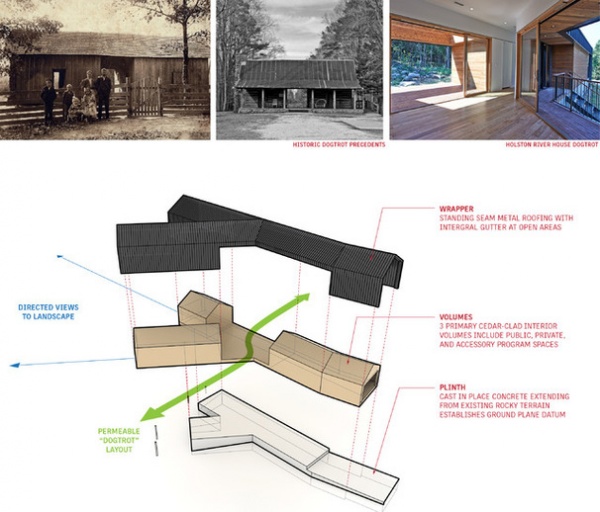

Design Workshop: The Modern Dogtrot

While the dogtrot house is primarily thought of as a Southern building type, its historical roots in the U.S. can be traced to the lower Delaware River valley colony of New Sweden — modern-day New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Delaware. The Swedish and Finnish settlers of North America in the 1600s brought with them a tradition of log building and the pair cottage. The pair cottage was a pair of log cabins set a short distance apart and joined by a sod-covered roof. The reason? Log cabins were limited in size (width, length and height) by the dimension of timber that could be easily managed using manpower and horsepower as well as the log’s taper. Longer logs had more taper and were less useful.

And because a log cabin’s walls were structural and not easily modified, when a log cabin became too small for a family’s needs, the logical means to expand was to construct another one right beside it; thus the pair. Roofing over the intervening space afforded the extension a covered breezeway that gained popularity for its utility.

Adoption of the dogtrot layout in the South grew because it offered another key benefit that Northern climates couldn’t fully appreciate: passive cooling. The covered dogtrot space, located in the center of the plan, offered not only a shady spot in which to relax (and for the namesake dog to trot), but the cooler pool of air could be drawn into the warmer nearby interior spaces by opening the doors and windows facing it. This passive cooling effect — stirring up breezes — was the real reason the housing type gained such popularity in the hot, humid climate of the southern U.S.

Although very few of the original colonial dogtrot houses survive, the plan layout as an organizational strategy is still relevant today. And here’s why:

Transition Space

We need transition spaces in our homes, whether they’re called porches, lanais, engawas or porticoes. These spaces that are neither indoors or out mediate grade changes, buffer climatic changes and protect us from the elements. The dogtrot layout has a transition space built in as a natural function of the plan. The roofed breezeway serves as an entry porch, a sitting deck and a gateway between house and site.

The floor of this dogtrot is at the same level as the interior of the home, but in early variants of this style, the floor was occasionally omitted altogether. This provided a covered place in which to repair equipment — a working porte cochere, or an early carport of sorts.

Keeping the floor flush is more convenient when the two flanks are used as living spaces, though, and the adjoining roof minimizes the waterproofing concerns that a flush floor or deck usually presents.

Separate but Connected

Many of my clients express a desire for separate structures on their properties. Whether they want a writing studio, a dedicated office space, a guest bedroom or simply a private retreat, the dogtrot plan serves this need in a simple, direct yet separated, house-within-a-house concept with little additional infrastructure. The covered roof allows all-weather access, and the separated structure also allows for part of the home to be completely shut down when not in use. A building that changes with the seasons is an inherently sustainable concept too.

Functional Separation

Historically, the two cabins (or pens, as they were called) flanking the dogtrot were of equal size and contained different functions. Cooking and dining were usually in one cabin, while the other was reserved for private living and sleeping spaces. This is part of the reason for the form’s enduring appeal today; it’s possible to have the benefits of clearly defined public and private zones in a diminutive and economical footprint.

This floor plan is a more contemporary interpretation of the idea that has unequal pens on either side of the dogtrot. Private, self-contained living quarters are situated at either end of the plan, and the kitchen, dining room and living room open onto the dogtrot.

Multiple Uses

Designing spaces that accommodate many different functions means we can build smaller. There’s a remarkable economy of function in the dogtrot plan, because the breezeway supports so many activities. Part porch, part entry, part hallway, the breezeway can also be a place for storing outdoor gear, hanging swimming towels in the summer, stashing skis in the winter or gathering around an outdoor fireplace.

It can be a dining room, a covered workshop, a game room, a screened porch or even a stage. Roofed indoor-outdoor spaces are appealing to us because they balance and satisfy so many of our basic needs at once: protection, enclosure, openness, natural light and fresh air.

Fireplaces

Adding a fireplace to the dogtrot can also enhance its function as a gathering place. In traditional dogtrots the fireplace was positioned on the gable end, away from the covered porch, but it’s easy to see why doing the opposite might make sense. In this modern example, the fireplace is incorporated into the breezeway, where it can serve both the interior living space and the outdoor porch. This further defines it as a destination for sitting and relaxing.

The Adaptable Side Porch

Usually, adding a porch to a home compromises the view and light in the adjacent space it serves. And, although it’s true that many dogtrots also had flanking porches, the fundamental layout of the dogtrot alleviates this problem, because the porch is placed to the side of the space, again proving its utility. This provides all the benefits of the porch without sacrificing natural light or ventilation.

Natural Ventilation and Light

As we touched on briefly already, in the era before air conditioning in the South, the dogtrot was a practical invention designed to passively ventilate the interior of a cabin. The shade of the breezeway set up a natural convective loop, drawing the hot, stale air out of the cabin via windows and doors opening onto the dogtrot.

Here the clever positioning of a large overhead door amplifies this effect, making the studio space one with the breezeway. The glazing and large door also bring lots of indirect, natural light into the room, making the studio seem much larger than it is.

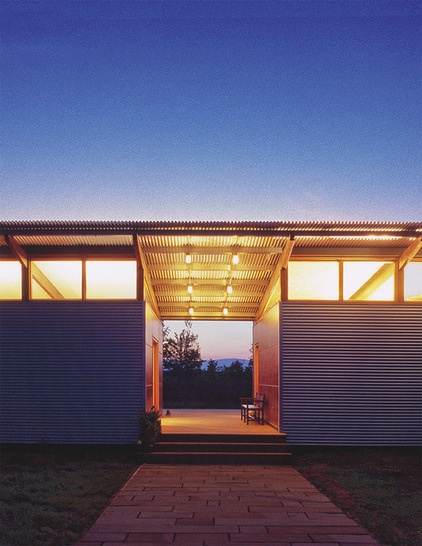

Materials

As you might have guessed, the dogtrot’s humble heritage begs for an equally humble exterior material palette. Corrugated metal, HardiePanel, Cor-Ten, rough boarding, metal or wooden shingles, or live-edge siding — they’re all fair game. I have a slight preference for selecting a single siding material, because it correlates with the simple geometry of the structure, but I appreciate the design thinking behind the contrasting warm wood in the breezeway seen here.

Size

The width of the breezeway in early precedents was a function of the logs, as was the sizing of the individual cabins or pens. Without heavy machinery to help lift the logs into place, carpenters of the time were limited to 16- to 20-foot-long ones. Stick framing, engineered timber and modern equipment have given us the freedom to size our breezeways and living spaces to meet our functional needs. This breezeway is narrower and is used primarily for circulation, connecting the two wings and serving as an entry porch.

The wider the dogtrot stretches, the more it becomes an outdoor room. Skylights brighten the lofty interior of this dogtrot.

Enclosure

The modern dogtrot can easily be made to adapt to the local climate, just as its historical precedents did. Adding sliding panels, or screens in this case, can extend the usefulness of the breezeway in shoulder seasons and keep bugs at bay.

Complete enclosure is another possibility. What it loses in openness, it makes up for in year-round function. Adding glass doors at the outer walls of the breezeway is a sensible compromise.

Inside, the breezeway area is almost as permeable between the flanks as it is on the exterior walls. The bedrooms can be open or closed, depending on the needs of the inhabitants.

New Possibilities

Contorted and tweaked, the plan of this home certainly challenges the notion of the typical dogtrot; it includes an additional wing and lacks some of the dogtrot’s inherent simplicity, but the tenets of the style are present, and the dogtrot breezeway is the hinge around which all the activity swirls.

Construction technology has afforded us the freedom to design whatever spatial configuration we can dream up for the modern dogtrot. No longer are we limited by log size and taper. And, while there are few remaining historical examples left, the dogtrot is once again gaining in popularity and being built in a variety of climates. I think it’s because it offers a simple, sustainable and utility-driven solution to so many of our living requirements.

It solves problems of privacy, entry, shelter and the desire for flexible space in a humble and affordable way. It introduces architectural diversity and interest to a simple plan layout that delivers enduring value to its inhabitants without great expense.

More: Time-Tested, Low-Tech Ways to Cool a Home