Design Workshop: How the Japanese Porch Makes a Home Feel Larger

I’ve written in the past about the essential nature of transitional spaces in a home, which are used to link interior and exterior areas. These spaces have been assigned a variety of names throughout the world — loggia, veranda, lanai, portico. Japanese architecture has its own version, called an engawa.

The engawa is a generous hallway, a roofed transition zone, located between the interior rooms in a Japanese home and the garden, created by extending the interior floor outward. It’s a room that defies traditional description — neither completely enclosed nor completely open. In Japanese culture it has a social importance, providing an informal meeting space, a place for sitting, greeting one’s neighbors and sharing a cup of tea. While it’s similar to other architectural elements, it’s also uniquely Japanese. But it’s worth considering in your own project no matter where you live. Here’s why.

Why would the Japanese, whose culture prizes every last square foot of space, give over such a large part of a home’s area to a seemingly functionless space? The reason lies in its diversity of function. It serves as a wide hallway connecting rooms, a sunshade, a wind buffer, a seat for viewing the garden or resting, an informal room in which to host friends, a step to move between garden and interior, a shelter from the elements and an expansion of interior space.

A Strong Connection to Nature

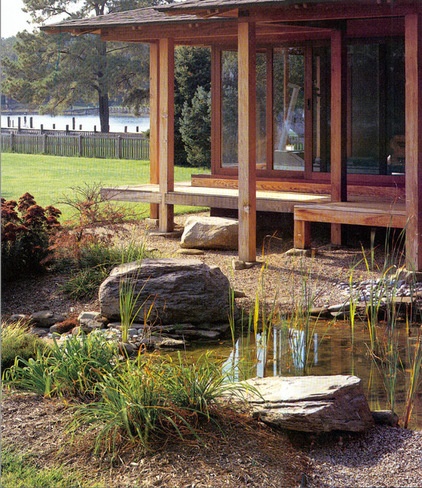

The engawa’s versatility is evident in the simple form of this cabin, designed for a couple of dedicated bird-watchers. As we view it from the gable end, we see that the center volume is flanked by two smaller slots of space — the engawa — which functions as a circulation zone and flexible screened porches. The engawa provides the frame against which to view the natural environment around the cabin.

On the interior we see the screened porch and circulation zone visible to the left, along with the sliding door, which can completely close it off from the living space. One has a sense for just how connected this arrangement allows the inhabitants to feel to the surroundings. Fully open to the sounds of the birds, the rain and the wind, this flexible porch allows them to have an intimately experience from the shelter of the home.

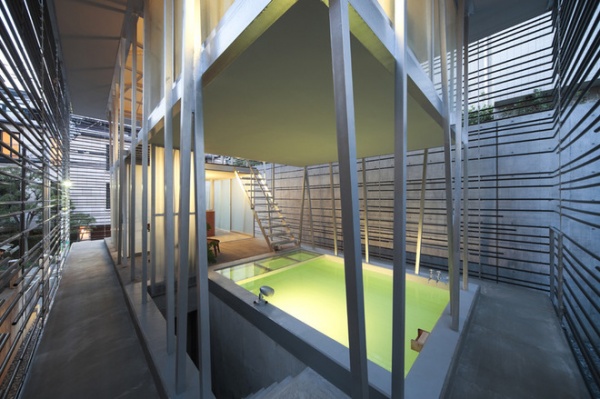

Japanese architecture prioritizes a deference to and a reverence for nature. Shaped by strict limits on available space, the architecture has developed to include many ways of appropriating small footprints into large gestures, ones that extend beyond their spatial constraints, making spaces feel larger. The curtain-wall house shown here is a great example of dedicating a large amount of space to an engawa in a small home. The porch establishes a connection to the city in this case.

Being able to alter the shell of a structure based on the natural rhythms of a place — daily or seasonal weather patterns — reasserts the importance of the natural environment in our lives.

Here the engawa is enclosed by a massive drape that the owners can alter (the drapery itself and via a set of doors) depending on the local conditions.

Flexibility

Creating a place that coexists with nature always requires some adaptation of the shelter to make best use of a particular environment. The engawa is an ingenious device for allowing a home to buffer climatic changes. It’s much like dressing a building in layers. Too hot? Slide open the shutters. Too windy? Slide them closed.

This project uses both the engawa concept, with sliding screens (seen to the left and right) as well as the more open veranda, or nure-en, seen in the center.

The sliding screens on the wings flanking the main living space can completely open the bedroom spaces to the courtyard. This is a very modern interpretation of a traditional idea but no less effective.

The engawa enables the spaces of the house to merge with the garden, the floor becoming a platform for entertaining, an outdoor corridor, an entry, a deck and a place for a seat. The roof offers shade and acts as a frame for the landscape.

In this project the engawa is present in the form of the structure and immediately visible, like the layers of an onion. The outer wrapper is a hallway bound by screens and the slightly more solid inner living space. Transition zones can lend varying levels of privacy to an urban site, making it feel more (or less) connected, as desired.

The outer walls of the same project are extremely thin, composed of pipes attached to a vertical framework. On this level the inner sanctum is dedicated to the owner’s dog, and the main living quarters are enclosed with sliding panels on the level above. Even in the city, a connection to the surrounding environment is important.

Gathering

The social function of the engawa is well documented. Much like the porch in the southern U.S., the engawa is a place for meeting and greeting friends and neighbors, acting as the most public face of a private realm. Because the floor of the engawa is even with the interior floor, its height is perfectly suited to function as a seating area.

Weather Protection

With the overhang of a porch and the flexibility of sliding interior panels, the engawa is an adaptable solution to a variety of climates. The overhang protects from rain while still allowing the interior space to remain open. It also promotes a primitive form of air conditioning, making it highly suitable for hot climates. By creating shade at the exterior wall face, it lowers the temperature enough to set up a natural convective loop that draws warm air out of the interior spaces to naturally cool them.

An overhang doesn’t have to be very deep to offer substantial weather protection, either. All it takes is a few feet, as shown here.

Depending on the climate, the outer doors of the engawa can be more or less open. These outer screens — similar to the Japanese sudare — are made of bamboo and hinge to either completely open the home to the garden space or close it off and protect it from the elements.

How to Use the Engawa

The benefits of the engawa can be achieved by following a few simple rules.

Transition space. Without a built-in transition zone between interior and exterior, the engawa can’t exist. Picture its simplest form: a rectangle surrounded by a slightly larger rectangle. The space between the inner and outer rectangle is the engawa, the transition zone. Imagine it as one long hallway connecting the garden and the interior.

Operable panels. The true engawa has sliding doors (fusuma) and screens (sudare, or shoji) on both the interior and exterior faces. Configured this way the engawa can act as a giant insulated shell for the interior spaces, and the prevailing weather patterns can suggest which panels are opened or closed. In temperate weather the interior panels can be slid away while the exterior ones remain closed, expanding the interior space. In cold weather they can all be closed; in warm weather, all open.

Continuous flooring. The floor level of the engawa should be at the same elevation as the interior floor, without steps. When doors or walls are opened, it’s important to maintain one level between interior and exterior so the spaces appear as a singular one.

Align the outside edge of the floor and roof. The roof should extend to the exterior face of the engawa, which establishes the protected zone. It should protect and shade but not obstruct; rather it should frame views to the site. Aligning the floor and roof completes the definition of the outdoor room, the transition space.

While these are some of the basic principles, the concept can apply to almost anywhere. It’s especially useful in small spaces. Create a large, multipurpose transition between inside and out and you’ll have achieved the primary goal of the engawa. Here you can see how it enlarges this interior space, exchanging a wall of glass for the forest edge.

The visual trickery makes small spaces feel much larger and introduces an adaptability that, besides being incredibly functional, is also inherently sustainable.

More:

So Your Style Is: Japanese

10 Japanese Soaking Tubs for Bathing Bliss