Design Workshop: 10 Reasons to Put Craft Into Modern Architecture

We live in a machined world, and consequently we have high expectations for perfection and quality in everything we own. You’re likely within arm’s reach of a beautifully designed, highly machined piece of technology — like the one you’re using now to read this ideabook. The industrial revolution has given us technology that’s made us more efficient and connected humans. But sometimes I can’t help but feel we’ve traded the handcrafted aesthetic for the universal; the unique for the ubiquitous.

I still find myself longing for the objects that bear the mark of the hand, the tool, the trade, the thought and care that went into making it, the craft. The Arts and Crafts movement in architecture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries had its roots in a very similar set of desires that rejected the aesthetics of technology in favor of the handmade. While it’s easy to get caught up in the freedom of high tech — and it has without a doubt made incredible advances in the look and construction of our homes — there’s still room for craft in architecture.

1. Craft is making. By definition the term “craft” means the physical act of making something with particular skill, usually by hand. “Craft” also refers to a vocation — someone’s craft. And it can refer to the object of the making — the craft.

The example shown here represents all of these. The craft of metalwork and its assembly is visible in the precise lines created by the water-jet-cutting process, a modern tracery in a massive sheet of heavy Cor-Ten steel, lending it lightness. The craft of the architect’s hand is present in the abstracted design — like sea grass — which reinforces the overall nature of craft in the project, where cutting and carving play a compositional role.

2. Craft is beauty. If you’ve ever attempted to assemble a kit of parts you lugged home from Ikea, you already have an appreciation for the skill it takes to create something beautiful from the raw materials of construction. Building is a complex and messy process. Craft is the veil for that complexity, in which years of skill are applied to a task and make its execution appear effortless and beautiful. Well-made things are beautiful to look at for so many reasons, not the least of which is our appreciation for the time and effort that went into their making.

3. Craft is detail. The objects we touch every day, the details of a home, are where craft really matters. Highly specific hand-wrought details such as those shown here are a delight to touch. They appear as necessary and cherished objects given a considered place in this kitchen. One has the sense that these objects will be passed from one generation to the next.

Saving the finest materials and joinery for the details we engage with most often is a wholly appropriate use of craft, especially when we can’t afford for every last inch of our homes to be fussed over. Craft doesn’t have to be expensive when used sparingly and thoughtfully.

4. Craft is subtle. The markings of construction, fabrication and connection are nuanced. You have to know where to look for them. When they’re left exposed, as in the boards of the concrete forms and the pockets of the form ties shown here, we have a greater connection to the process that shaped them. Subtly tattooed on the face of the wall here, the imperfections create shadows and places for moss to grow and connect the wall to a history of making.

5. Craft is authentic. Materials joined and celebrated for their unique properties feel right. Steel is strong and planar; using large, thin sheets of it makes sense. Wood is warm and light. It’s harvested and machined very differently, because the raw material is very different from steel. Logs are of a fixed length and circumference, and sawing them into sticks makes the most efficient use of their size.

Plainly exposing the burned edges of reclaimed wall studs as boards cladding a new wall is an open, authentic expression of this home’s historical past (the home was gutted by fire).

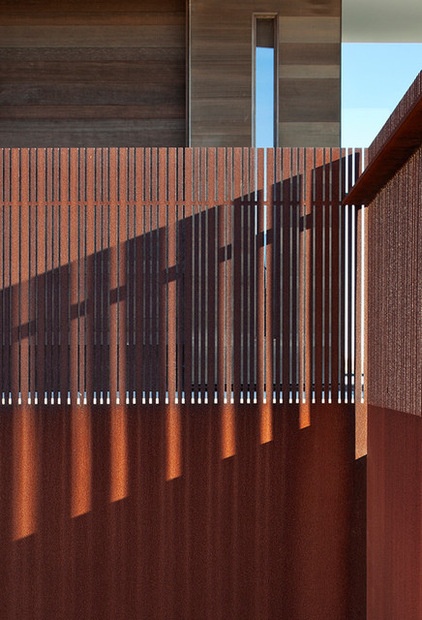

6. Craft is expressive. Much of what our homes are actually constructed of is hidden behind layers of drywall or plywood and cladding. Craft plainly demonstrates the role of each component in the greater whole. Here a light steel structure sits lightly on the land, concealed by an even lighter wood screen. The openings of the screen are determined by the need for intermediate structural blocking, but equally the slits imitate and abstract the surrounding forest. They also partially conceal a butterfly-shaped roof, which directs water to a nearby cistern.

We often hide the joints between materials because they’re messy, but craft expresses the intersections of the materials and the necessary joints they share. Here the stone surround and wood window frame are expressed in a carefully constructed reveal.

7. Craft is unique. To the situation, location, fabricator, installer and user, craft is unique. It reflects the precise intersection between function and beauty. It carefully measures and customizes, allowing things to work exactly as intended.

There’s a notable, intentionally designed family of details at work in this photo. The repeating L shapes of the wooden shelves and the handle speak the same language while being made of different materials. There’s a functional directness to the design, which proudly displays its assembly while still deferring to the books. The very uniqueness and care with which this bookcase has been treated suggests a certain importance in the owner’s life.

8. Craft is deliberate. The crafted solution takes into account the fundamental properties of the materials used. Here the mass of concrete is thick and heavy, while the metal appears as a thin liner, its edge turned up at the intersecting joint. These considered design decisions, even in something as simple as a sink, feel right because the materials require it. If we make concrete too thin, it will crack, while thin sheets of steel are easy to bend, lighter and less expensive.

Unlike with the Arts and Crafts movement, adopting craft doesn’t also require rejecting the aesthetics of technology. The machined and handmade can coexist when the decision is made deliberately. The marriage of old and new allows one to appreciate their differences.

9. Craft is imperfect. Our consumer culture has taught us to expect perfection in everything we buy, and we extend that same expectation to our buildings. It’s understandable given the high cost of custom construction, but the reality is that what it costs to achieve perfection in construction is often far beyond what any of us can afford.

The Japanese are known for their aesthetic of imperfection; it’s called wabi-sabi. Things don’t always line up, edges aren’t always clean, metals patinate, concrete sprawls; life is in general a pretty untidy business. When we consider the fact that for the most part, people — not machines — still make our buildings, why should we expect robotic perfection from them? Acknowledging the beauty in imperfection can be difficult but liberating.

10. Craft is collaborative. While architects and designers are responsible for design, our profession is unique in that the way our designs are realized is through the work of many. Clients, contractors, subcontractors, consultants, artists — they all have a hand in contributing to the work of architecture. Embracing the contributions of each individual can make for a richer project whose sum total is far greater than any one person’s contributions.

The physical manifestation and making of architecture is often far removed from the designing of architecture. For architects, designers and contractors alike, sharing in the making of things is a chance for everyone to set aside their egos and appreciate the unique challenges that custom design and construction present. This appreciation for the work of others often provides novel insights and positive new design iterations and can’t help but further the craft of architecture.

More: 8 Things Successful Architects and Designers Do