Design Practice: 11 Ways Architects Can Overcome Creative Blocks

Architects and designers are under constant pressure to summon creative forces into action on a moment’s notice. We visit our clients’ homes or their building sites and are expected to produce the imaginative vision for transforming them into masterworks on the spot. Creativity lies at the heart of every design process — and it can be an elusive muse at times.

When your professional competence relies on rousing an idea out of the ether, the creative block can be paralyzing. Rest assured though, it happens to all of us. I’ve come to believe that it’s actually a part of my process and that it strengthens the designer within. Knowing this, however, doesn’t make it any less troubling when it happens. So here are 11 ways I’ve found to help me get out of a creative rut.

1. Keep an idea journal. Filling a journal with ideas certainly isn’t unique to the design profession; many disciplines rely on the concept of stockpiling ideas for use in leaner periods. As a creative person your ideation process is likely continual, producing some that are great and some that are not so great. The idea journal is a place for those ideas to incubate and even meet each other. I keep an Evernote notebook on my phone, labeled “Ideas,” for this purpose and I know it’s never far when I need it. Sketchbooks or Moleskines work too, although I don’t find the ideas to be as accessible as a digital log. It’s worth carrying these ideas around with you all in one place as combining ideas often results in unexpected synergies.

Creating Houzz ideabooks is also a good way to keep track of ideas you might want to try on a future project.

See how to create and use ideabooks

2. Cross-pollinate. Step outside of your profession and view the problem at hand through a different lens. This could be the lens of other individuals you know or other fields of study. How would an engineer or a scientist solve the problem? How would your grandfather solve it? How would a child view it? How about a miner or a mariner? Dropping your own professional baggage and assuming someone else’s can help lubricate the imagination.

3. Exercise. The link between creativity and exercise has proved somewhat elusive to scientific research thus far, but exercise’s effects on the brain are well documented. Altering brain chemistry, reducing anxiety and enhancing the ability for the brain to forge new neural pathways are among the positive changes exercise induces. Scientifically proved or not, I find that exercise engages parts of my creative brain that I can’t access any other way. It forces me to get out of the studio, away from my drafting table and into a different environment. I’m able to think about and process connections that weren’t previously apparent to me.

Not to mention the full complement of other physiological health benefits that come with routine exercise. If you pair your exercise with a chore such as mowing the lawn you’ll even have something to show for your creative holiday.

4. Invent obstructions. I think every designer should watch the movie “The Five Obstructions,” in which Lars von Trier sets mentor and fellow filmmaker Jørgen Leth with the task of recreating his favorite film, The Simple Human, in five different ways. For each of the five iterations the director imposes a constraint on the filmmaker, an obstruction, resulting in a different film. It’s a deep dive on the often maddening struggles we face as creatives and our ability to turn apparent obstructions into opportunities.

Your project may already suffer from too many obstructions, but if those aren’t inspiring you, try imposing a different set of constraints as a way of re-framing the problem.

5. Play. Break out the Legos, wooden blocks, a game or an instrument and play. Like exercise, play has been shown to reduce stress and anxiety and improve the cognitive function of your brain.

There was a study conducted in the early 1980s that tested the creative problem-solving ability of preschoolers. One group was given a set of puzzles — problems that have a single solution. Psychologists call this convergent thinking and play. The second group was given blocks to play with. Blocks are an example of divergent problem-solving toys, meaning they yield multiple solutions.

Not surprisingly, when comparing the two groups, the children who were given the blocks to play with performed much better on tests requiring creative problem-solving skills to complete, problems that lacked a singular clear answer. The problems of design are by nature divergent, where multiple solutions are possible.

Embrace the idea that as a design professional your career involves tasks that most others would consider play, and use it to move through your creative drought.

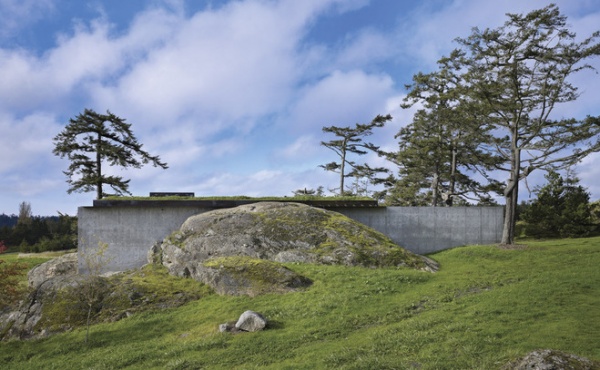

6. Make it monumental. There’s great power in a simple but forceful gesture. The “art barn” shown here is a good example. Or think of Maya Lin’s iconic Vietnam War Memorial, a metaphorical and physical scar on the landscape. Hers was a singular, monumental gesture.

Try inventing a monumental solution to your problem. What if the entire design were a really thick wall, or a giant window, or paper thin or a lantern? What then? Think of this purely as a means, not an end — a bridge to transport you to the final idea.

7. Set a deadline. How often do you wait until the last minute to complete a task? Somehow you find a way to compress eight hours of work into four hours of time when you absolutely have to. Working toward a deadline can leverage our natural inclination to procrastinate and then, seemingly impossibly, deliver. We can reproduce some of the same mental processes that allow us to get the work done on a tightened schedule.

8. Write. You’re probably used to sketching to solve design problems. I use it frequently to process information and formulate ideas for my work. But I also find that fleshing out a problem in writing can produce similar results. Switching up the medium you use to communicate ideas forces you to articulate the problem with a different level of insight and clarity.

The writing can be a fictional creative exercise used to tell the story of the project, its history, how it came to be, who the main characters are, the setting and the plot twists. Or it could be true to life, descriptive and technical where the text relates the finishes, the lighting levels, the mood and how one arrives at and moves through the project. You’ll be calling on a different part of your creative self for help. It works well.

9. Consult the masters. The design challenges we face as architects and designers today aren’t fundamentally different from our ancestors’. Modern life benefits from technologies that they couldn’t even dream of, but at a basic level we’re solving the same problems that our kin were a thousand or more years ago: the functional need for shelter.

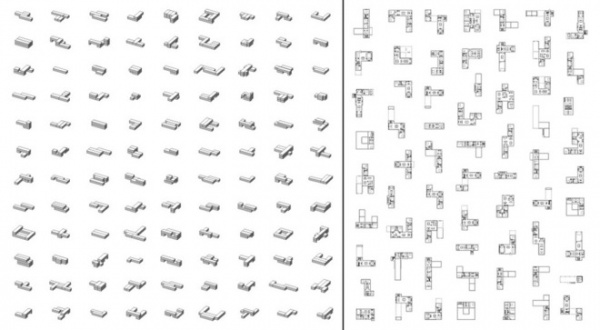

Look to the masters of the built environment at varying scales for inspiration throughout history. Borrow their ideas, their concepts and their organizations, even just to test them on the problem at hand. We’re taught very early in school to conduct precedent research before designing. Practice this in your professional life too and it’s almost guaranteed to spark a fresh approach to an age-old problem and set your design process in motion.

10. Design a detail. Challenging yourself to solve all of a project’s problems at once can be the source of the creative block. Zoom all the way in and allow yourself to design a single detail. How might the stairs work, or the entry wall, a gate or a corner? By freeing your mind up to solve a small problem sometimes the larger solution presents itself.

11. Do the work. One of my favorite quotes about inspiration comes from author W. Somerset Maugham, who said, “I write only when inspiration strikes. Fortunately it strikes every morning at nine o’clock sharp.”

Sometimes the only thing left is for you to sit down and do the work. Showing up every day and practicing your craft means confronting periods of less than ideal outward creativity, which we mistakenly correlate with productivity. It doesn’t mean you’re broken or inept, rather that there are ideas incubating and brewing inside. Setting your hands in motion to do the work is the only way to truly move past your creative block. The ideas have to come out.

More: 8 Things Successful Architects and Designers Do

Your turn: How do you battle creative blocks?