Design Workshop: Smart Ways to Store Wood Outdoors

Shorter days and cooler nights are a reminder of how much I look forward to the fall, but also that winter isn’t far away. I watch the hard frost creep closer my studio here on the East Coast with each day, and I realize that it’s probably time to stack that firewood I’ve been drying over the summer.

In colonial America the woodshed was an essential part of the homestead that protected a hard-won resource from the weather and allowed it to season, or dry. It was usually attached to the home, allowing for easy access in the dead of winter and to the outhouse when combined trips made sense.

The amount of wood necessary to heat a home today is far less than in colonial times, but at 128 cubic feet (4 feet by 4 feet by 8 feet), a cord of wood is still a large amount of space to account for. Whether you heat entirely with wood, or it supplements another heat source, or you just like the flicker of fire on a cold night, you still need to keep your supply dry. And you might as well store it in style.

There are generally four practical things to keep in mind when designing an outdoor wood storage shed: size, location, protection and air circulation. (There are additional things to think about, but more on those later.) Let’s look at the basics first.

Size

Your first task is to decide how much wood you want to store. Firewood is sold by the cord (and fractions thereof), which, when stacked, is 4 feet deep, 4 feet tall and 8 feet long. Because standard firewood splits are 16 inches long, a 128-cubic-foot pile of wood is essentially three rows of split logs. A face cord is one-third of a full cord, essentially one of those three rows: 16 inches deep, 4 feet tall and 8 feet long.

A face cord is usually adequate for limited seasonal or aesthetic use only, whereas one or more cords would serve an average, well-insulated home as a primary heat source (wood boiler, stove etc.). Of course, all of this depends on house size, climate, heat loss and insulation, so consider these rough guidelines.

Keep in mind when sizing your storage that any wood kept above shoulder height will be both difficult to stack and harder to access during the heating season.

Location and Protection

Historically, firewood used for heating and cooking was stored outside but close to the kitchen. Storing firewood close to its point of use is certainly convenient in the winter, when access can be made difficult by snow and ice, but getting it all there — the chore of stacking — can be cumbersome. How much wood you’ll be storing will inform you location choice as well.

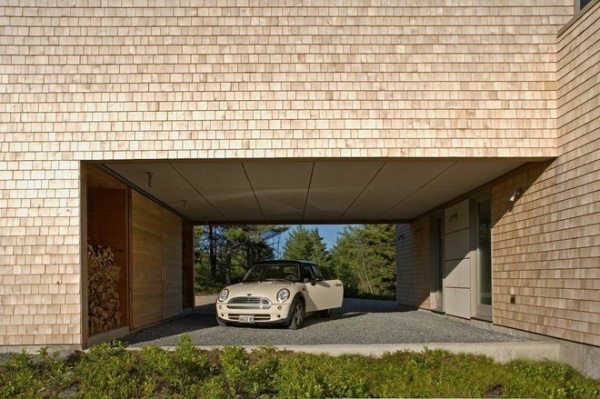

The integrated wood storage in this carport is an ingenious solution, and between the two sides, it can store quite a large amount of wood. The choice to place it close to the entry means it’s a short distance between the spot for wood delivery and the storage cubbies, and an equally short distance (and covered path) to inside.

The porch. Because porches are transition spaces, they also make great wood storage areas. They allow you to bring an armful of wood on your way in or easily reach it from inside without shoveling a path to a remote shed. If your porch is generously sized, you may already have a built-in woodshed of sorts.

If your porch has a wood deck, make sure that the framing is adequate to carry the higher loads of stacked (and often wet) cord wood before stacking. Getting wood up off the deck surface will preserve the decking and allow the lower logs to remain dry. Rubber horse stall matting can make for good protection when stacking on wood porches, too.

Tile, stone or concrete floors are the best solutions, because they’re durable and don’t get marred with the abuse that stacking can inflict on a wood deck. But even with those materials, it still makes good sense to elevate the stack for drying.

Pair the porch with clever design details like this and they’re even more appealing. This firewood loading door has been stationed near waist height to allow the logs to be passed inside to the adjacent wood storage bin with ease. The bin corrals the log debris, and the mudroom location is a smart choice. Mudrooms, like porches, are transition spaces with durable surfaces and lower room temperatures, which allows cold logs to warm up without introducing lots of heat loss into a living space designed for relaxation.

The alcove. Recessed areas designed specifically for storing firewood are great solutions when the amount of wood to be stored is less than a cord.

Located near the door and under a sheltering overhang, this firewood storage smartly integrates intermediate plates in the larger alcove. The divisions make removing logs from the stack more manageable. The plates are self-supporting at the sides, so it’s possible to remove a log from the middle section without affecting the top or bottom. The proportions of the subdivisions nicely match the door sidelights, and the wood is a pleasing textural element against the smooth siding.

If you do opt for an alcove, line it with a durable material or use a finish that you won’t mind marring over time. Metal, concrete and stone, as discussed previously, are all virtually indestructible choices.

Stand-alone shed. If you decide that the integrated approach is too permanent or restrictive from a size perspective, the freestanding woodshed is an option. Stand-alone sheds were once commonly used in New England for commercial activities, like maple syrup production or commercial woodlot operations, and were usually located near a road. Siting a shed remotely usually means easier delivery and stacking, but the further it is from the home, the more difficult it will be to use in the winter.

I love the idea of actually making a firewood shed outwardly express the firewood as an aesthetic decision, as this shed so plainly does.

Separate structures can conceal the stack (which can appear messy), reference the architecture of the home and allow the wood to be off the wet ground. Oftentimes they’re open on one side for easy loading and unloading, and their sides can be more or less open to allow for ventilation.

See how to add a backyard shed for storage

Air Circulation

It’s always a good idea to allow adequate ventilation around your firewood. But it’s especially true if you purchase your wood “green,” or unseasoned. Green, freshly cut firewood is less expensive, but it has an extremely high water content and needs to be dried for six to 12 months before burning. This not only will ensure that you’re getting as much of the heat energy out of it as possible, but also that it won’t promote creosote build-up in your flue.

You can use the need for air circulation around firewood to your advantage, though. By placing it as a buffer against the wind, you’ll dry the wood while preventing those cold winds from stripping heat from your home, a win-win.

Design Ideas

With the practical concerns addressed, let’s think outside the shed for a minute.

Integrate. As an architect, I am always attracted to the more integrated solutions to a problem. Here the architect has matched the roof geometry and design language of expressed framing in this simple wood shelter. It’s positioned near the entry porch and protected from the elements. Integration doesn’t have to involve great expense, just a little consideration and basic design thinking.

Bound by concrete walls, this integrated firewood storage feels tonally right at home with the material palette of Cor-Ten and concrete.

Hybrids. Sheds so often become multipurpose structures, housing not only firewood but an array of other outdoor equipment and tools. To that end, why not craft a shed that stores more than just wood?

Consider this lightweight shed with a roof clad in solar panels, storing both wood as heating fuel and sunlight to use as supplemental heat.

Make it an experience. The mandate for a log home inspired this architect to construct the exterior walls with split logs. The entry view shows how the wood is positioned to act as an exterior insulation blanket. There’s a delicate balance between the aesthetic game the architect is playing and the wood’s insulation value, but using split firewood to buffer the harsh weather of the site is meaningful on many levels.

As we dig a little deeper, the architect’s careful attention to the experience of the inhabitants is equally interesting. Note the thin metal frame marking the perimeter frame of a window. The wood stacked inside the frame obstructs the view, but as the Montana winter wears on and more wood is consumed, more light is permitted into the space behind.

Perhaps a metaphor for the changing light as spring approaches, this also gets at the very nature of what it means to burn wood to heat your home. It’s a process of moving logs from outside to inside, and you watch the stack melt away as spring inches closer. This process undeniably enriches the experience of living in this home.

See more of this home

Here’s another wonderfully simple example of a similar idea. If you’ve ever stacked wood, you’ll appreciate the advantage of having side walls that brace the stack.

Seek inspiration in other structures. Outbuildings often present interesting opportunities to be bold and rethink even humble structures like the woodshed. Imagine a woodshed that also doubles as an outdoor fire pavilion, in which walls of stacked wood act as a backrest to a central fire pit. Taking cues from architectural follies such as this one can spark new ideas and turn mundane, utility-driven outbuildings into destinations on your property.

More: Find a Fitting Place to Store Your Firewood