Houzz Tour: A Stunning Low-Energy Home in the Cotswolds

Hill Barn is a 300-year-old stone structure at the top of a hill in the heart of the Cotswolds, England. Architect Chris Seymour-Smith and his wife, Helen, know the property well, as it sits on land belonging to Helen’s father, in an official Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Helen’s father and previous owners had tried and failed to get planning permission to convert the derelict building, including the drummer from Duran Duran, who wanted to turn it into a studio, says Chris. Undeterred, Chris, of Seymour-Smith Architects, applied under the Exceptional Country House Rule. “Only about four houses a year are granted permission under this rule,” he says, “and each property has to be truly exceptional.”

The new home extending off the barn, called Underhill House, is certainly that. Dug into the hill and invisible from the surrounding countryside, the contemporary home was designed to Passivhaus standards, resulting in a 90 percent reduction in carbon emissions compared to that of an average home. In fact, Underhill became the first certified Passivhaus in England. “Passivhaus has very simple principles,” says Chris. “The houses are superinsulated, airtight, ideally point south to maximize solar gain and are triple glazed.”

Houzz at a Glance

Who lives here: Chris and Helen Seymour-Smith and their son

Location: The Cotswolds, England

Architects: Seymour-Smith Architects

Size: 4 bedrooms, 4 bathrooms

It took around 18 months to build this groundbreaking property, which Chris and his family moved into in 2010. “Inside it has a wonderfully fresh, still atmosphere,” says Chris. “There are no drafts, it’s very quiet and yes, you can open the windows!”

As for the logistics, “we made a 3D model on the computer of a mile radius around the site,” says Chris. “We used this to work out how low to position the house — we just kept dropping it down until we couldn’t see it anymore.” He and his team ended up digging down around 10 feet. “As you go up the hill along the drive, you can see the entrance, but that’s it. From the local area, the house is hidden.”

The original barn that adjoins the new house has been converted to Passivhaus standards, too, with plans to use it as an office. Solar panels flank the south wall. “From March to October, we have free hot water,” says Chris. “From October to March, there isn’t quite enough sun, so we installed a very small wood burner with a back boiler. You only have to light it once to top up the house’s thermal store for two to three days.”

Chris installed a shallow slate pool by the house. “I’ve always liked water close to architecture,” he says. “When you open the windows, you get a nice breeze of fresh, ionized air blowing in.” This section of the house faces west. “When the sun hits the pool, it creates lovely dappled reflections on the bedroom and study ceilings,” Chris describes. The pool quickly became a home to frogs, newts and grass snakes. “If you change the environment back in favor of nature, it quickly takes advantage and rushes in,” he says. “Within six months this pool was full of wildlife.”

This space, above the house and flanked by the barn wall, is what Chris calls “the G&T [gin and tonic] terrace.” Instead of a solid, white-painted parapet, he installed this palisade design. “It breaks up the space and makes the most of the views, too,” he says. “You can see three counties from up here: Oxfordshire, Gloucestershire and Warwickshire. It’s gobsmacking!”

Chris used as many recycled materials as possible in the house. “It’s made from an ecoconcrete, which contains 70 percent recycled materials,” he says. “The paviers [pavers] on the terrace are made using waste from the china clay industry, so they have a lovely white gleam and help bounce light into the house.”

Planning officials would not allow Chris to put a roof on the ruined part of the barn, behind the house, so he and Helen use this area as a kitchen garden. “Where the barn remains open to the sky, we’ve made two large planters from oak railway sleepers,” he says.

Triple-glazed windows make the property airtight. Air is filtered through a heat-recovery ventilation system, which removes stale air and any damp air from the kitchen and bathrooms, and replaces it with filtered clean air with no loss of heat. “It creates a very fresh, clean atmosphere inside the house,” says Chris. “It’s ideal for anyone with allergies.” The temperature generally stays at a constant 68 to 69 degrees Fahrenheit, and there are no drafts. “The first year we lived here it was 5F outside, and there was snow right up to the house, but even then, inside it was a comfortable 66F,” he says. The triple glazing means the house is also very quiet. “We live quite close to RAF Brize Norton and get huge Hercules planes flying over,” says Chris. “You can see them, but you can’t hear them!”

“The house started out as white,” says Chris, “but as we lived here, we thought about where we might want some color.” The living room now has a red feature wall enveloping the wood burner and log storage. “Most of the house is still white, but we wanted to punch in some color,” he says.

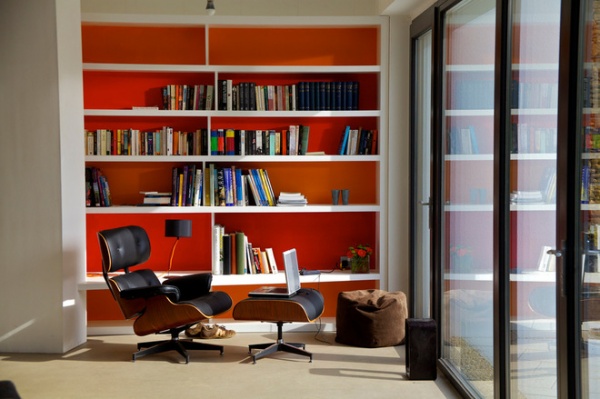

A library corner forms part of the large, open-plan living space, which also has a sitting area, dining space and kitchen. “It’s lovely reading next to those large French windows,” says Chris.

To improve its efficiency, a Passivhaus has no cold bridges. “In an old-style building, you have a solid brick wall, which is cold outside and warm inside, with no insulation,” says Chris. “This is a cold bridge. People then often insulate their properties inside to some degree, but little areas, such as the space around a window, remain. Heat transfers through these pockets of cold space, which means you lose energy and often get mold growing, too.” A Passivhaus design avoids these cold bridges and small gaps in insulation. “It’s about nibbling away at all those parts of a home that lose energy,” he explains.

“We lived in the smallest Georgian cottage in London before moving,” says Chris. “ Our furniture would have been lost here.” So the couple had most of the furniture made to fit the house. The dining table is made of oak planks, cut from a tree that was blown down on Helen’s father’s farm a decade ago. “Then we used steel left over from the build for the base,” says Chris. “We had to hold up the barn with massive supports while we built the new house. Once the structure was in place, a local blacksmith cut the supports to make the table legs.” The table is never covered. “I know every wine stain on it from every party,” he says, laughing. “We like furniture that has a story.”

“We wanted the house to feel as fresh and open as possible,” says Chris, “so we didn’t want curtains.” Instead, a blind fitted externally reacts to a sensor. When there’s too much sun, it automatically comes down to control the amount of solar gain and prevent the room from becoming too warm.

While the main living rooms and bedrooms border the terrace, all the ancillary rooms are on the hill side of the building, which has no windows. Here there is space for a media room, study, utility room and wine cellar, plus a storage area that doubles as a gym.

More: In the U.S. this building approach is called Passive House. Learn what it is and why you should care