What We Can Learn From Longwood Gardens’ New Meadow

I recently came back from my first visit to Longwood Gardens, in southeastern Pennsylvania. Since I’m a Great Plains boy, my center of the universe is what most people call flyover country — perfectly spaced grid lines mapped out in the 1800s by Thomas Jefferson. I can see storms coming half a day away.

Since it was my first time in that part of the eastern U.S., I felt as if I was in another world altogether — the houses and trees were right up against the road, so as I drove around I felt a keen since of claustrophobia and an inability to focus on anything. This is also how I tend to feel in many botanical gardens and arboretums — I’m overloaded by design and plant material. Even at Longwood, the impressive gardens and conservatory did little to make me feel at home.

Then, as I stepped onto a wooden bridge above diverse woodland-edge perennials, I viewed through a distant clearing what was for me a welcome embrace. In Longwood’s new 86-acre meadow garden are lessons about sustainable gardening practices, which have been trickling down through professional and weekend landscapers. What can we learn from the meadow for our own gardens?

Info: Longwood Gardens is open year-round; days and times vary by season.

This vista awaits you at the end of the first bridge. The meadow, designed by regional landscape architect Jonathon Alderson, is not a return to a plant community that once was, per se, but is a melding of what was and what works well in this space. As seasons change, new plant communities will emerge, and the designed drifts of plants as well as the more integrated, or “wild,” meadows will be highlighted in different ways.

This land was once used to grow crops and raise livestock, dating back to the mid-1700s. In 1906 industrialist Pierre S. du Pont purchased the land to preserve the wooded areas, using the meadow area for farming. In the mid and late 20th century, the meadow was slowly reenvisioned, and Longwood finished the job this year.

First, I’m in love with these Cor-Ten steel information signs. You’ll find info on the vista as well as maps of the 3 miles of trails. What’s new about the meadow? A hundred thousand native flower and grass plugs, 1,100 native trees and shrubs, 110 new plant species and 95 identified bird species.

Sometimes the meadow vista can become overwhelming. I know to many early settlers of the Great Plains (which has many of the same plants as eastern meadows), such spaces seemed like a desert. But when you stop, perhaps lean down or get on your knees — up close and personal with a bloom, like these Liatris flowers — the perception focuses and you find entry into something larger. I know we all experience this sensation in our home gardens, and then we look at them in different ways. This is one of many things I think the meadow garden at Longwood teaches us. What else can we learn?

1. Good things happen where ecosystem edges meet. A meadow is simply a sunny clearing in the woods or forest, a place where shorter perennials can gain a toehold before the surrounding trees fill in. At the edges of different landscapes — like where marsh meets field or woods meet meadow — is a rich transition zone of plant and animal life.

At Longwood’s forest-edge covered pavilion along one path and near the tree line, you’ll see this lesson stenciled on cuts of native tree trunks. The edges where landscapes meet are places where there’s more diversity in plants, which means more diversity in butterflies, bees, birds etc – it’s like two worlds merging. Think about how a patch of unused lawn beneath your trees could be a condensed meadow, or what would happen if you install a small pond that welcomes in life from trees, shrubs and flowers all around. (All life needs water.) A meadow will breed insects that tree-nesting songbirds feed exclusively to their young.

2. The importance of native pollinators. At another pavillion is a native bee hotel where you can observe the more docile native bees making homes for their young. It’s easy for you to make a native bee house, too, by drilling various-size holes into untreated blocks of wood, or even using hollow-stemmed perennials like Joe Pye Weed.

See how to build your own bug habitat

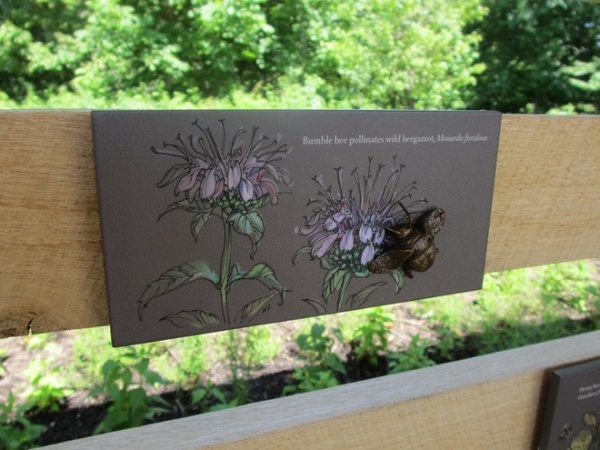

Inside the shaded Pollinator Pavilion, local artisans have created textural plates showing the relationships between certain insects and meadow wildflowers.

Some of the many plants you’ll see in bloom include: allium, Joe Pye Weed, milkweed, aster, sedge, fern, turtlehead, sunflower, coreopsis, goldenrod, verbena, monarda, penstemon, mountain mint, rudbeckia, ironweed, culver’s root, bluestem, prairie dropseed and sideoats grama. All of these support a diversity of insects that help flowers produce more seed and feed other wildlife, like birds and amphibians.

3. Native plant communities that might work in home gardens. Though meadows change from week to week, on any one visit we can see where plants are thriving, and other plants they are growing with. I was surprised to see Joe Pye Weed in huge swaths on a sloped hill — I’d normally expect it to be in wetter areas, like at the bottom of a slope where water gathers or along a marsh edge. Realizations like this will help you experiment at home, giving you confidence to see what happens when you stop trusting plant tags and go with what you see in nature.

In addition, certain plants like legumes (purple prairie clover, lead plant) create nitrogen in the soil, a key plant resource, while others, like bluestem, lean on sunflower for support.

I visited in early June in the garden’s first year of establishment, and by midsummer the perennial flowers and grasses will be many feet high. What will they look like in late summer or fall? How much more fantastic will they appear in coming years?

Landscapes teach us patience as we live on a plant’s time — a good lesson indeed. Remember the gardener’s adage “Sleep, creep, leap”? The first year plants sleep, the second they creep, the third they leap (and the fourth they go gangbusters).

4. Create surprise and intrigue that elevates the garden experience. This is a bridge that spans a dry creek bed, or overflow, from Hourglass Lake. It’s planted with meadow flowers on the edge, and the path is lawn.

In our gardens we can use elements like bridges and curving paths to create surprise and even whimsy. Maybe it’s fun to bring tall plants close to the path instead of placing them in the typical back of the border. Maybe it’d be neat to place pots or sculpture among the flower beds. What if your path were made of lawn or crushed gravel or even sedge instead of traditional mulch?

5. We can learn about citizen science, seeing deeper and caring for the planet. Longwood is testing to see how green roofs on bluebird boxes affect how many eggs are laid and the health of young bluebirds. The roofs decrease the indoor temperature by a few degrees, and volunteers monitor the boxes during nesting season, when 170 birds fledge annually.

We can do the same in our landscapes — observing nesting birds, pollinating insects, when plants emerge and flower each year — all information that’s critical for scientists to monitor in a changing climate. This is why citizen science programs are so important, and even fun for the family that gardens together.

Learn more about citizen science programs

At the Hawk Point pavilion, you can look up and see the silhouettes of various birds circling in the sky if you poke your head out. It’s easy for us to focus on the ground beneath our feet or immediately in front of us, but we don’t take enough time to look up and around. If you do, you’ll get a better idea of what’s using your garden space and what those things need to survive (trees, flowers, water, open space).

6. Get lost in a place and a moment. The meadow garden is large, but you can take any number of short or long circuits. Whichever way you go, the art of getting lost is paramount. This is an unobtrusive garden where you learn about it by experiencing it, which is perhaps the truest sense of a garden. Take this lesson home and get lost in your own garden; take your time, stop and listen, smell and touch, and let the garden bring you down to earth — it’s why you planted it in the first place, right?

7. Connect the past with the present to create a future we might want. It’s always been important to me that gardens bridge the past, present and future. The meadow garden employs many plants native to the area and placed in their ecological niche.

When our gardens honor what used to be there by using natives, we help the wildlife that is still there and depends on those native plants while helping to ensure that organisms like insects — which give us one in three bites of food through the act of pollination — will be here in the future. Up at the 1700s-era Webb farmhouse (shown here) you’ll find a gallery of the meadow’s history and agricultural use, along with the ecological roll native plants play.

Longwood’s meadow garden will change and evolve, as any landscape does. It teaches us that a garden is not a static painting or sculpture, but that just as we change course over time, so does nature — which we are a part of, which we depend on.

If we depend on it, it’s key that we help it remain resilient. If we can plant a diversity of native plant species adapted to our areas that feed wildlife, we are doing our job as gardeners and land stewards — and the icing on the cake is that we can observe even more beauty that brings us home.

More: 3 Ways Native Plants Make Gardening So Much Better