Design Practice: How to Pick the Right Drawing Software

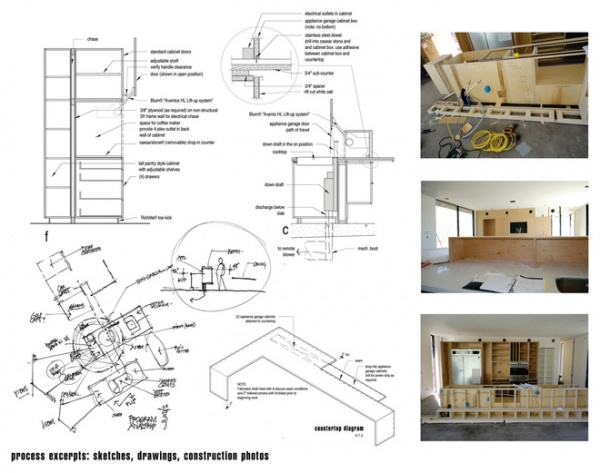

Parallel rules, circle templates, vellum, drafting dots, erasing shields … you may still have some of these implements on your desk for sentimental or nostalgic reasons, or your projects may begin there, but it’s probably been a long time since you’ve actually inked a set of construction documents on Mylar to run through a blueprint machine. At least, I hope so.

Drawings remain the primary means by which architects convey ideas to the craftspeople who will manifest them into tangible structures, just as they have been doing for a very long time. The way we create those drawings has evolved over time and will continue to. But no matter what, the way you put a set of drawings together — the line weights, shading, notation, what you choose to draw and what you leave out, the unspoken gestures of delineation and representation — are by extension a part of your brand. And that means you’ll need the right tools for the job.

To select the software that’s right for you, I recommend starting by answering this question: “What’s the best way for me to channel my creative energies into a representation that someone can build from?” The answer will be different for all of us, but let’s briefly review a few of your options.

It’s important to remember that drafting and design software, like anything else, is just a tool. And unless you’re willing to dust off the drafting board and break out the pounce (remember that stuff?), you’ll need a drawing tool in the form of CAD (computer-aided design) software to create your drawings in an efficient manner.

CAD software can incite great passion among architects and designers. I understand just how personal a decision this is, because it’s used almost every single day. So my goal isn’t to endorse one tool over another. That would be the equivalent of my telling you to sketch using only an ultrafine-point black Sharpie when you prefer Sign Pens or crayons. This is really more of an overview or guide for navigating the choices. It’s up to you to decide which one best fits your work habits and your brand’s message.

2D Digital Drafting vs. 3D Model Making

Up front you’ll need to decide whether to invest in two-dimensional CAD or a three-dimensional BIM (building information modeling) system. Two-dimensional CAD is purely representational drawing, or digital drafting. Lines represent three-dimensional objects using standard drawing conventions.

They don’t correlate to each other or ever coalesce into an actual model of the structure. You create drawings based on architectural standards (plans, elevations, sections) to represent that building three-dimensionally. It’s completely up to you to create the appropriate drawings needed to illustrate the characteristics of the building coherently to those responsible for constructing it.

By contrast, with BIM, you’re drawing the actual walls, roofs, columns and other building components that contribute to the creation of a model and a true (full scale) three-dimensional representation of the structure you’re designing. The model is imbued with all of the real-world characteristics of a physical building, such as windows, doors, hardware and wall construction. BIM allows you to create a single, “intelligent” model, in which each of the components drawn exist as parametric, information-rich objects.

When you insert a window into a wall in the plan view of your model, it comes with a definable subset of information (type, size, color, glazing etc.) automatically associated with it.

Your drawing set is essentially extracted from the model by viewing it from different vantage points (a plan view, section or elevation). The real power is evidenced when you make changes. For example, when you move a window in the model, any of the drawing sheets (views) you’ve created that reference that particular window will reflect this change automatically. So too will the plans and sections, which can reduce your coordination and drawing time significantly.

There’s a fundamental difference between modeling the building and creating static 2D drawings to represent it.

2D CAD

In the 2D CAD world, AutoCAD (made by Autodesk) is the dominant player. The light version (LT) is an affordable entry point, at $1,200 to buy it outright, or there’s a subscription option available for $360 per year. However, LT lacks many of the bells and whistles of regular AutoCAD ($4,195, or $2,100 per year) or its even more robust and fully featured cousin, AutoCAD Design Suite ($5,245, or $2,265 per year). The latter has has additional architectural design and presentation tools specifically geared toward design professionals. (See the details of each iteration.)

Trimble’s SketchUp is free and can also fit the bill using LayOut with a little additional effort.

Two-dimensional CAD is essentially digital delineation. You construct the sheets based on your knowledge of how a drawing set is crafted. In this way it can be time consuming, repetitive and redundant. But if you’ve been using two-dimensional CAD for any length of time, there’s an inertia to overcome. You probably have a set of conventions in place and a working method that you don’t have to think about. In this way I think 2D CAD is great at getting out of the way. However, there’s just no getting around the fact that it’s inherently more inefficient than other means of drawing, because it requires so much input and coordination from you, the user.

You will also require some additional software to account for the lack of 3D integration. You’ll likely want to visualize your work in 3D, and for that you’ll have to look to other programs to fill the void 2D CAD leaves.

Advantages of 2D CAD:

Cost effective; low initial investmentDrafting concepts are basic and easy to learnQuick means of generating 2D document setsIndustry-standard file conventions (.DWG, .DXF) ensure you’ll be able to collaborate and exchange data with other pros and consultants

Disadvantages of 2D CAD:

Lack of 3D capabilities means other programs must fill those needsCross-coordination and set management (changes) take more time. Not the most efficient workflow. Particularly evidenced when making changes late in the construction document stage.The industry is moving away from 2D standards to BIMTedious, repetitive drafting tasks (trimming, extending etc.) are baked into 2D drawing

BIM

In 1984 Graphisoft introduced ArchiCad, a computer-aided drawing program that endeavored to go beyond the mere digitization of architectural drawing. The goal was to infuse a three-dimensional interactive building model with layers of real-world information. The company created the foundation of what we call today BIM, or building information modeling.

Ten years after that, in his architectural practice, Frank Gehry began using CATIA, a highly specialized 3D program geared toward the aviation industry for integrating the many geometries and systems required of a complex machine. Today his company, Gehry Technologies, is one of many software companies leading the charge toward technology-driven architectural project delivery.

The power of a 3D BIM design strategy is that it embodies a different and more integrated way of thinking about design. Creating a single digital model of your building means you’ll have a more robust picture of exactly how all of the real-world building systems interact.

We’ve all had the hand-to-forehead experience of arriving on a jobsite and seeing a beam where that line of recessed lights was meant to be. BIM seeks to eliminate these types of problems before they arise in the more costly environment of the construction site by integrating them in a shared digital model.

With BIM you create a single 3D digital model of your structure, onto which you layer information as you move ahead with the design. In this way your plans and elevations and sections and details are all connected, which is a very real-world way of thinking.

Unlike 2D CAD, the BIM drawing set is generated by capturing different views of this information-rich model. Because you update the parametric objects within the model when making changes, the revisions are automatically present in each of the views (drawing sheets) you’ve created.

The big players in the BIM space are: Revit Architecture ($5,775, shown in this photo), Revit LT ($1,675); ArchiCad ($4,250) and Vectorworks (from $2,595). Even SketchUp 2014 ($590) is BIM compliant. And there are many, many others.

There are many reviews of the nuances of each one of the programs that can be found online as well. And, given the vastly different pricing, it pays to do your research. Some of the less expensive versions (such as Revit LT) lack some very useful tools — energy and structural analysis, for example — and limit the number of people who can work on a model at once. So while Revit LT may provide the sole practitioner with entry-level BIM, it probably won’t work very well for firms with multiple employees sharing drawing tasks.

Advantages of BIM:

Fully integrated workflow: Changes made to the model appear in all views created from the modelAllows more thorough coordination of building systems, such as M/E/P, structural and landscapeLess time on tedious drawing tasks equals more design time for youCan be a competitive advantage in certain environments, especially those requiring BIM as a deliverable

Disadvantages of BIM:

Higher costHigher up-front investment in both learning and drawing/modelingStill often requires the integration of 2D CAD for certain drawing tasksPlug-ins may be required to achieve optimal drawing output

While the up-front input time is greater, the model, the net result, is an infinitely more adaptable databank of raw information to pull your drawing set (and schedules) from.

Small firms may be insulated from the BIM movement for now, but know that it will impact the future of all practicing designers and architects.

How to choose? There’s a reason this exists as a debate in professional circles: It’s not an easy or straightforward decision. However, you’ll never be better positioned to make this type of choice than when you’re starting your firm. Once you’ve built a workflow and developed projects using a specific CAD system, it will be more difficult to change later. Large firms especially struggle with this question, but you, as the small (or solo) firm owner have it easier. You can pivot with relative ease, and your low overhead is a real advantage.

If you’re not already beholden to a 2D or BIM solution, I think the choice is quite easy, if you can afford it. Select a BIM platform and build your workflow around that. This is especially true if you plan to grow your practice beyond just yourself, because your future employees are all being trained to incorporate BIM into their design production processes, so leverage this fact.

Once you’ve learned the software and established drawing conventions (line weights etc.), it’s inherently a more efficient methodology for putting together a set of drawings. And the larger and more complex project you do, the more this holds true.

If you’ve been using 2D CAD to produce drawings, the decision is more nuanced. Downtime, at least initially when you’re building your practice, is something you may have more of than you’d like. Use that down time as an opportunity to invest in learning a new program and making the move to BIM.

On the other hand, downtime when you’re a sole proprietor trying to get the job done doesn’t pay the bills. It’s easy to fall back on familiar systems that work and produce results. CAD is just another tool at your disposal, so you should treat it as such. There’s nothing that suppresses creativity like going to battle with your CAD system. Don’t fight this. Draw by hand if you must.

You may even consider outsourcing your BIM or CAD work or hire someone in-house to execute your vision. If the tool is getting in the way of your doing your best work, abandon it for something you can work with.

Presentation Drawing Software

If you haven’t selected a 3D CAD program that handles modeling and presentations, you’ll probably want to have some means of creating digital models and renderings.

SketchUp is an obvious choice. It’s a free, intuitive modeling program that I can’t recommend highly enough. The 2014 Pro version ($590) allows better integration with external CAD programs and a more robust feature set. Either one can be used as 2D, 3D and BIM, and they’re both a steal for the functionality and design horsepower they bring to the studio. As a bonus, the learning curve on the modeling component is so low that I’d consider it to be almost nonexistent.

The rendering possibilities are limited with SketchUp, so if you need high-quality, ray-traced renderings, you may want to consider a third-party application or plug-in to handle those needs. I use the Maxwell for SketchUp plug-in ($99), which is an unbiased rendering engine that sits inside of SketchUp and allows for photorealistic renderings and advanced material assignments. There are others too: V-ray ($750) and Podium ($198), to name just a couple, and each have their own learning curve.

More robust rendering and modeling programs, like Maya ($3,675), 3dsMax ($3,675), Form-Z ($1,390) and Rhino ($1,295 and up), are worth considering if higher-level modeling and presentation tasks are part of your workflow. These are expensive programs with substantial learning curves. For a residential practice, they’re probably more than is necessary, at least at first, but the beauty is, it’s your firm — you get to decide. If you have experience in any of these programs and can bypass the learning curve, the higher up-front investment may pay for itself quickly in time saved and results achieved.

WorkPod - GBP 9,950Photoshop, InDesign, Illustrator

I think it would be hard to find an architect not using an Adobe product in some part of the presentation workflow. These products are all available via subscription and pay-as-you-go models. For as much as you’ll need to use them, you may find that an outright purchase makes the most sense, whether it’s a single license of Photoshop ($699) or InDesign ($699), or access to the Creative Cloud ($50 per month).

Buying all of this software outright can add up to many thousands of dollars. Subscription, or pay-as-you-go, pricing models are an extremely useful thing for new firms. Purchasing a month’s time to use an extremely powerful product required to get the job done certainly fits the lean start-up model we’ve been following and ensures you’ll pay only for what you need.

All of these options have some form of a free trial. So if you’re at all on the fence, give one or two a test drive to see if the technology opens up new and better ways for you to design and deliver a better product. If so, then it probably is worth an investment of your time and business dollars.

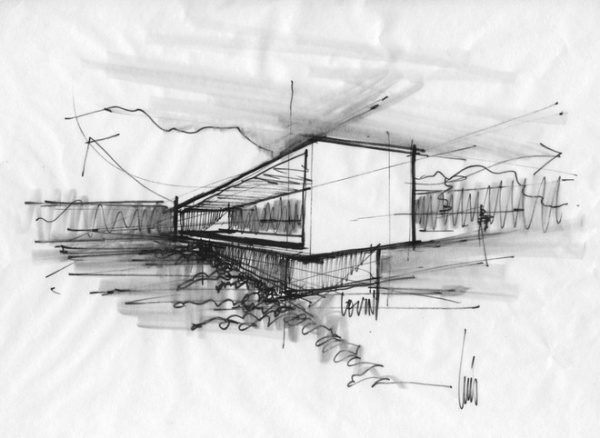

Hand Drawing

Even though we’ve moved away from the drafting table, there’s a reason the iconography persists. Architects draw and sketch. No matter what software tool you choose to help you do that, no skill is more potent or valuable, even in our technologically advanced world, than hand sketching.

The first lesson that the great Carlo Scarpa taught at the beginning of his design studio course at the IUAV School of Architecture was how to sharpen a pencil. Great architecture follows from the thoughts and ideas present in the sketch. As a designer it’s something you’ll perfect long before you purchase CAD software, and it will serve you for your entire career.

And pencils don’t require upgrades.

I’d love to hear what’s working for your business. What do you use to draw?

More:

How to Start Your Architecture Business

The Basics of Marketing Your Business

How to Get Hired

How to Ensure the Best Client Experience

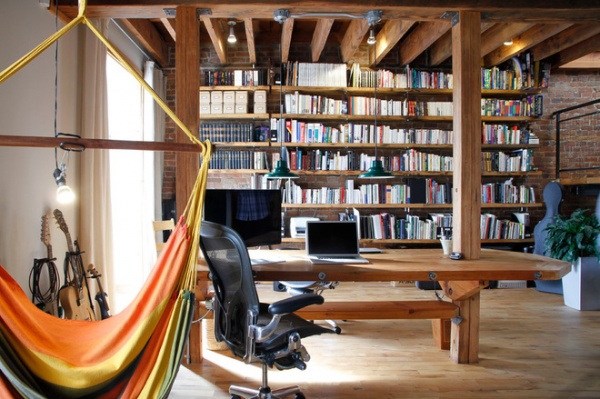

Setting Up Your Studio

6 Drawings on the Way to a Dream Home