Taking Cover in a Former Nuclear Missile Silo

In the early 1960s, faced with the imagined scenario of total nuclear annihilation during the Cuban Missile Crisis, a dozen intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) silos were constructed in the Adirondacks in upstate New York near the former Plattsburgh Air Force Base. The crisis lasted less than two weeks, and because the silos didn’t work very well anyway and had a lifespan of around three years, most were decommissioned by 1964.

The military didn’t know what to do with the silos, which were vast, cavernous underground structures that went 185 feet down and housed Air Force squadrons. They donated the silos to different counties, who didn’t know what to do with them either. So they remained abandoned for more than 50 years.

Eventually, people like Australian architect Alexander Michael came along. He snatched one up near the Plattsburgh base in 1996 for $160,000 and has spent the years ever since plunking down more than $300,000 and restoring his silo to its original glory, while making it a part-time home along the way. He’s got a full kitchen, sleeping quarters and even the original launch control console to tinker with.

Michael says he’s not a Cold War enthusiast or military fanatic. Rather, as a designer, he’s interested in such a utilitarian structure designed specifically for function. “I find things like these silos and military bunkers extraordinary in their focus on purpose,” he says. “They’re designed with nothing but functionality in mind, and that creates the most interesting architecture. Aside from the cool factor, of course. How many people do you know that can say they own a nuclear missile silo?”

He’s spent more than 15 years restoring the silo, financed by his work as an architect and the sale of a one-bedroom apartment in Sydney. “I didn’t like that apartment, so I thought I’d buy a nuclear missile silo instead,” he says. “I can’t tell you how much joy it’s given me.”

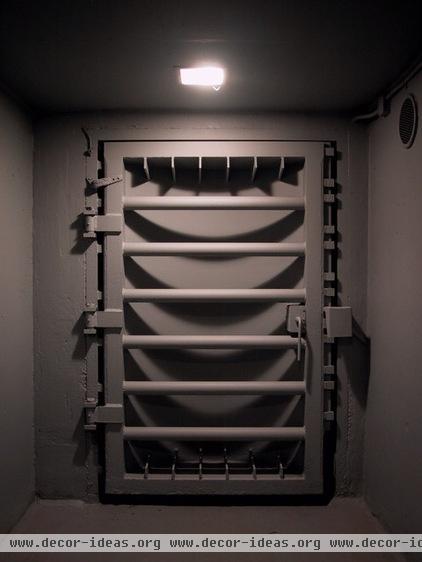

The front door, seen here, is known as the entrance portal. It leads to a stairway that immediately descends underground about 30 feet to the control center. The entrance portal was built with reinforced concrete designed to be expendable, Michael says.

If the silo were ever destroyed in a nuke blast, the entrance would deliberately collapse, and the only exit would be through an emergency escape hatch, a concrete tube filled with sand that leads from the control center to the surface. You’d open the hatch, release all the sand, put a big ladder up there and hightail it out. “Though I’m not sure why anyone would want to get out if there’s been a nuke blast,” Michael says.

Michael splits his time between Australia and the silo, where he spends most of spring and fall. Two ventilation pipes — one for intake and one for exhaust — connect to the surface. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, these vents were shut down. An enormous exchange system original to the silo is still used to circulate air.

“As soon as I arrive after being away for a while, I turn on the vent system,” he says. “Because everything is underground and tightly sealed, you don’t get dust or anything. Everything looks like the day you walked out, completely and utterly exactly the same. The air will be a bit musty, but after an hour and a half of running the system, it’s clean and sweet.”

He says the space is so vast, 52 feet in diameter in some parts, people rarely feel claustrophobic. “I’m not permanently there anyway, so it’s not an issue,” he says. “I live in Sydney with one of the greatest views in the world of the opera house and harbor, so I get my fill of views.”

Plus, he’s got a bank of monitors on the wall that show what’s happening on the surface. “This is quite important, especially when you lose sense of time quite easily because you don’t have the usual markers like natural light, the sun or moon,” he says. “I’ve got 20 clocks down there, too.”

At the bottom of the stairs, you must walk through a “convoluted passage,” says Michael. “This was to stop unlawful entrances but also to stop pressure from a nuke blast by bouncing the waves off concrete walls and through a series of blast doors.”

As for the appearance, you won’t see any bright colors or graphic wallpaper. “I wanted to keep it like a nuclear bunker,” he says. “I wanted it to look exactly like it did when airmen entered it.”

The damage in the silo was extensive when Michael bought it. Water and humidity had caused rust and deterioration, making the restoration painstaking and slow. Michael had to sandblast the blast doors, like the one shown here, take them apart and reassemble them, then repaint and add a rustproof sealant. “There were four of them, and it was a big exercise,” he says.

Since most of the original military designers, builders and contractors have died, Michael relied on his own expertise and that of friends to help him figure out how things worked and fit back together, making the process arduous.

One thing Michael didn’t keep was the paint color. “The original color was really, really awful, a very pale yellow-green, pretty much the standard color that the Air Force used in these military installations,” he says. “It wasn’t a color I could live with. So what else could it be but battleship gray?”

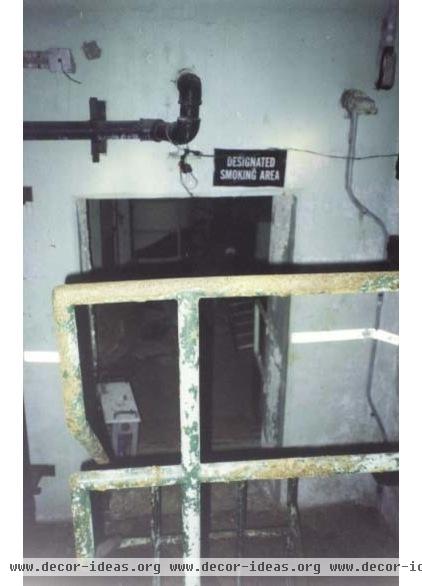

Here you can see the original color on the rusted rails. This stairwell connects the two levels of the control center.

AFTER: The middle of the control center was originally designed as a sphere, because that was the most structurally efficient shape. But it was too difficult, expensive and time consuming to build, so the designers changed it to a cylinder with a flat roof. Because it’s not as structurally viable, a massive central support column (seen here) ensures that the structure and earth above don’t collapse.

The handrail around the cylinder shows how the control center isn’t actually attached to the walls or column, but rather suspended from four hydraulic arms to cushion the entire living level from shockwaves.

Years ago Michael got to test the system during an earthquake. A friend called him up to ask if he’d felt the strong earthquake the night before. “Not a thing,” Michael says. “I was disappointed, because I’d never experienced one.”

This is part of the former control center.

AFTER: Michael turned it into a living room. You can still see the sign with the escape hatch instructions.

The open door leads to the bathroom. You can see how the roof of the bathroom sits considerably below the actual concrete ceiling. This shows, again, how the living quarters are suspended, and how things like water pipes and electrical lines are loose fitting to be flexible if the living levels were to shift during a blast.

The bathroom is the only space in the complex that is 100 percent original — the sink basins, toilet pans, shower closet, lighting … everything. “Mind you, it was disgustingly vile and took a lot of back work and disinfectant to make it come back really fabulous,” he says. “Of course, not that many people are impressed with it, though.”

Even the plumbing system, being underground, was virtually intact. Everything, including the 90,000-gallon water reservoir that feeds into the silo, is original. Michael flushed the line — “A lot of nasty s**t came out,” he says — and got it operational. “I didn’t have to pay for new plumbing, though, and all the faucets are original. It just amazes me.”

A large septic tank is housed in the silo. All sewage gets pumped up to a commercial-scale leaching field. “I just changed the pumps, and the whole system worked and came alive,” he says.

As for power, the silo was originally on the town’s grid, because the military didn’t want to continuously run operations from its two huge generators when not on full alert. This made getting the electricity back on fairly simple.

Here you can see one of the monitors showing closed-circuit video of the world aboveground.

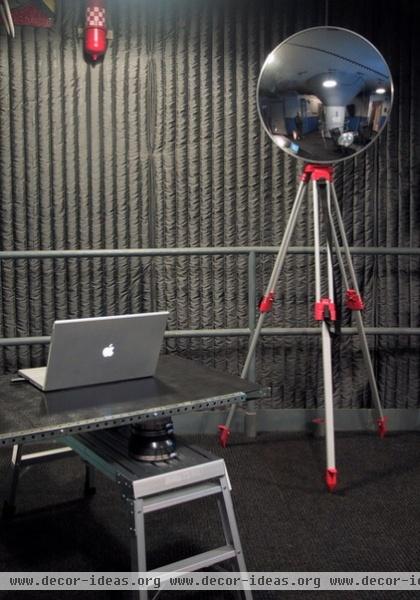

While Michael strived to keep the space as original as possible, he did have to add some conveniences to make it more comfortable and good-looking. In the living room, for example, the original curved concrete walls of the control center created resonant sound and radiated cold air. To fix this he draped the walls completely in quilted gray fabric. “It stops the convection of air hitting the walls and cooling down,” he says. “It helps kill the sound as well.”

The floor is still original “olive and drab” vinyl tile, Michael says, but the tiles were so damaged that he covered them with commercial charcoal-gray sisal carpet.

Not much furniture was left behind. “I did find a desk that had been thrown down the silo, but it wasn’t good enough to restore,” Michael says. So he designed and built pieces himself, like this computer desk constructed from pieces of industrial equipment.

The convex mirror on the tripod is one of several in the silo. Though Michael has backup power now, several times he had to position the mirrors during power outages to reflect sunlight from the surface, through the hallways and into the control room.

For the TV room, Michael purchased several mobile surgical army lights from an online army surplus store for $150 each. “It’s the most immaculate thing you’ve ever seen,” he says. “Every detail is stainless steel and shockproof.”

The original kitchen was “surprisingly mundane,” Michael says. “You kind of expect your mum to be standing there in a smock cooking up dinner.”

He says he would have restored the cabinets, but everything was beyond repair. “And I didn’t want to make a reproduction of it,” he says. He took everything out and added white tile and stainless steel pieces.

AFTER: In one part of the new kitchen, Michael displays old pieces of equipment found scattered around the site. “These are original computer banks, not quite what we imagine today,” he says.

This is where the airmen originally ate. Michael chose all period furniture for the space. The chairs are circa 1960 and fiberglass. Multiple clocks help him stay in sync with reality above.

Michael turned the lower level of the control room into sleeping quarters. He designed the big platform beds with industrial wheels and grab rails. “It’s just like a kid’s fantasy in there,” he says.

The original launch control console remains in this space, and Michael (not shown) is in the process of restoring it.

There’s also a small sitting area for reading or watching TV. Again, Michael selected furniture that was designed during the 1960s. He found this Eames chair in a junk shop for $150.

About seven years ago, Michael heard a rumor that the original silo door actuators — big hydraulic cylinders that opened the 90-ton doors — were in a junkyard not far away. He and a friend spent two days digging through the yard and finally found them. He traded in an old six-wheel-drive military vehicle and some cash for them.

He installed one of the cylinders and got it functional, allowing him to open one of the silo doors, seen here. Once both are operational, he’ll be able to create a 40-foot by 20-foot opening in the ground to flood the silo with light.

Even though Michael recently finished the control-center living space, the restoration is an ongoing process. He’s now working on the actual missile silo itself, which is a 185-foot deep space that’s 52 feet in diameter, seen here during an indie film shoot (the missile is a prop). You can see the massive doors on top that open to the world.

He wants to turn the missile silo itself into a performance space. He recently let the indie film director’s girlfriend, a concert violinist, play there, and he became hooked on the idea. “It was the most exquisite thing you’ve ever heard,” he says.

This is a rendering of Michael’s vision for the missile silo doors. The idea would be to let the silo doors open to allow natural light in but keep weather out.

Michael stands in the utility tunnel, which is the only pedestrian access into the silo where the original missile was kept. This is where all the cables and coolant lines run.

For now he hopes to get everything ready for June 2014, when the new Cold War Museum opens in Plattsburgh. Servicemen from the original silo squadron will return to tour the space for the first time since it was decommissioned. “I’m interested in sharing my home as a design exercise and not just a crazy Australian living in a hole,” he says.