How a Minority Changed the Face of Design

http://decor-ideas.org 04/10/2014 03:22 Decor Ideas

Spurred by good economic times and the desire for new aesthetics not associated with World War I or II, midcentury Americans embraced modern design. According to a new exhibition set to open at San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum, the movement was driven by a relatively small number of Jewish people in the United States. Designing Home: Jews and Midcentury Modernism explores how Jewish architects and designers changed the look of our homes and and the things that fill them. It’s the first exhibition to explore the topic, and it runs from April 24 to October 6, 2014.

According to Donald Albrecht, guest curator for the exhibition, a number of factors in postwar America led to the phenomenon. He says that many Jews immigrated to the U.S. in the 1930s and ’40s to escape anti-Semitism and persecution. Among them were key members of the Bauhaus (a German design school dedicated to using all elements of art and design to reimagine the material world). The ideas of this movement took root and began to flourish in American soil. In the exhibition catalog, Albrecht writes, “The Bauhaus saw the design of the modern home as a means of reaching a wide audience and focused on developing new forms of domestic architecture, interior design and household products."‘

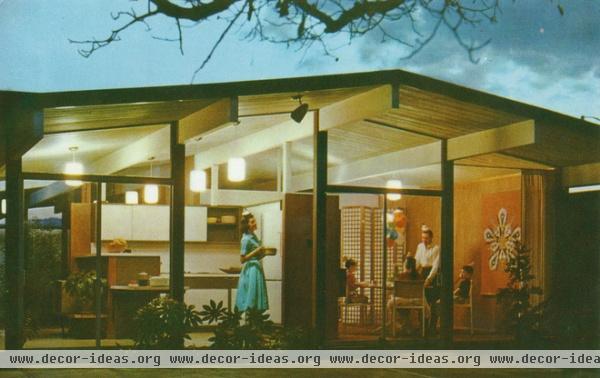

Among the items on display is this Eichler model home advertisement from 1960. Joseph Eichler, one of the first developers to champion and promote modernism, went against the grain of that era. He had a strict nondiscrimination policy and sold homes to people regardless of race or religion. When the National Association of Home Builders refused to adopt his policies, he withdrew from the organization.

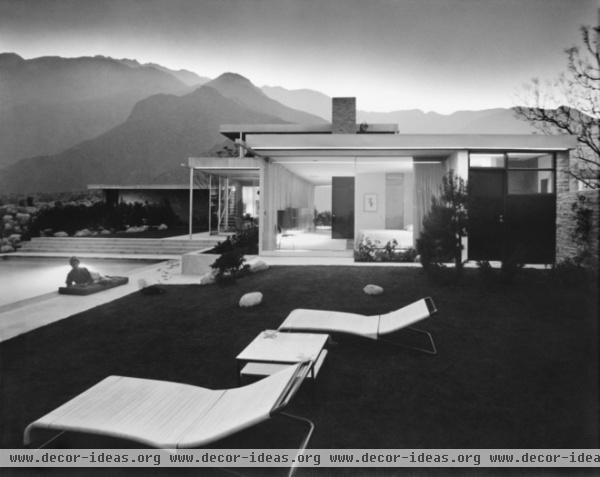

Another image included in the exhibition is Julius Shulman’s photo of Richard Neutra’s Kaufmann House. Edgar Kaufmann earned a fortune through his chain of department stores. His son, Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., was the director of industrial design at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. There he started the Good Design program in 1950. For the next five years, the program, which included a number of influential Jewish designers, exhibited cutting-edge yet functional household products to a public that seemed to have an insatiable appetite for the topic. It did much to influence the look and feel of the times.

Perhaps Kaufmann was inspired by his father’s Palm Springs, California, home, which was designed by Neutra and embodied the spirit of modernism.

The Lustig chair, designed by Alvin Lustig, the revolutionary graphic and typeface designer, is just one of the iconic furniture pieces included in the exhibition. It has been in production since it was created in 1944.

“After World War II, there was an equalization in America for the Jews,” says Albrecht. “They were more accepted into the mainstream, and this gave them freedom. Many of the boundaries were erased.”

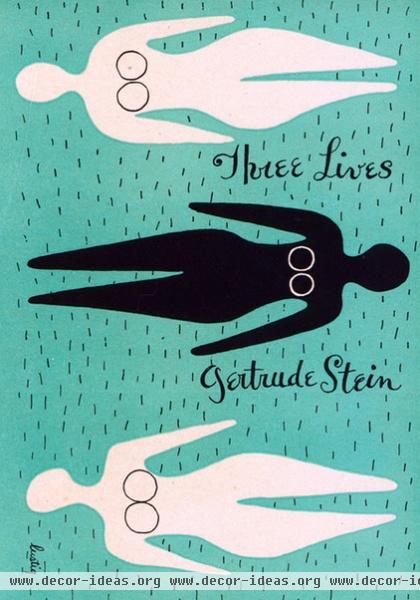

Lustig’s graphic design work, an example of which is shown in this book jacket from the exhibition, did much to set the visual tone of the times.

The work of Ruth Adler Schnee, pictured with her textile Slits and Slats, is also in the show. In Germany she was part of the Bauhaus school, where she studied calligraphy. But after her family’s home was destroyed during Kristallnacht, she and her family fled the country. In America she became a revolutionary textile designer. Schnee and her husband, Edward Schnee, opened a store in Detroit, and they were the first to sell modern fabrics and furnishings.

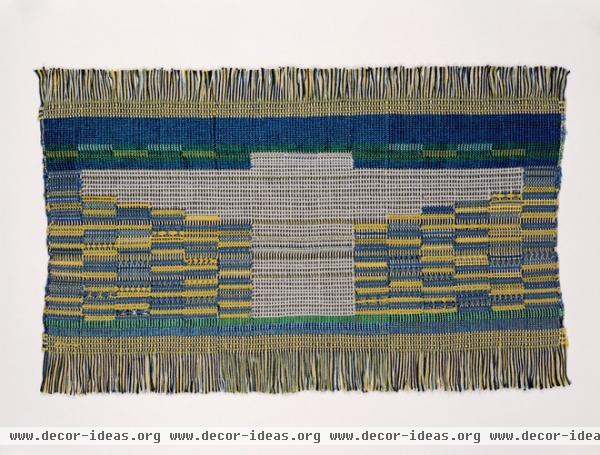

Also on display are the weavings of Anni Albers, another female textile designer who studied at the Bauhaus. Anni and Josef Albers came to America to teach at Black Mountain College in North Carolina (an institution Albrecht says was seminal in Jewish midcentury design work). Her woven wall hangings embody the look of midcentury modernism.

Among the display items are more workaday items — including the Princess Phone, by Henry Dreyfuss. Dreyfuss was like the Steve Jobs of the era, in that he obsessed over the design details of the objects we interact with every minute of every day. His work became so popular, he became a celebrity industrial designer.

Dreyfuss hit one design home run after another — including the Big Ben alarm clock.

His Honeywell Round Thermostat was developed to solve a design problem. According to Albrecht, “He noticed that many rectangular thermostats weren’t squared on the wall. Not only was the round thermostat easy to operate; it was impossible to install crookedly.”

The abstract forms of this coffee set were created by Eugene Deutch, a ceramicist committed to making functional items beautiful. His rustic tableware, lamps and containers are modern masterpieces.

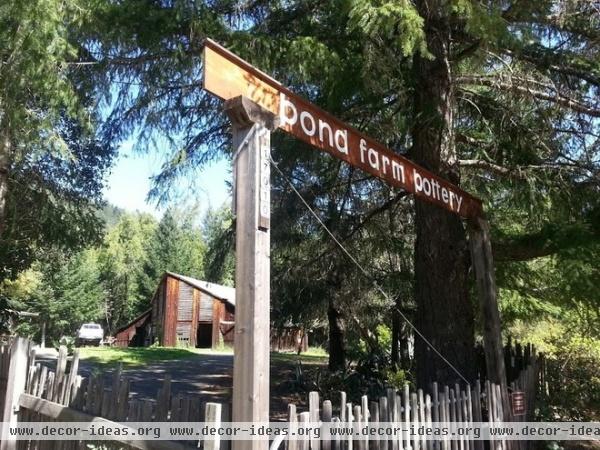

Art and architecture were explored at Pond Farm in Sonoma County, California — an influential artists’ colony. The founders decreed that the colony would be an “artists’ refuge in a world gone amuck.” When it fell apart in 1953, the remaining artist, influential Bauhaus potter Marguerite Wildenhain, ran it as Pond Farm Pottery, and she taught there for many years.

Albrect says Wildenhain’s life is just one of the many stories visitors will uncover. “It’s interesting that in midcentury America, Jews made up just 3 percent of the population,” he says. “But what’s fascinating is that in the area of design, they had much more than a 3 percent impact.”

Exhibit info: Designing Home: Jews and Midcentury Modernism. April 24 to October 6, 2014; Contemporary Jewish Museum, 736 Mission St., San Francisco, California; (415) 655-7800. More info

Related Articles Recommended