How to Help Your Town’s Beneficial Birds and Bugs

Urban Hedgerow, an art and ecological collaborative in San Francisco, has been planting wild habitats in the city landscape since 2009. In addition to raising public awareness of and creating discussion about the importance of the beneficial bugs and wildlife in our built environments, the group is also beautifying it, leaving custom bug boxes and public habitat sculptures as calling cards, spreading the word of our silent allies through the dwellings they inhabit.

Though more people are recognizing the importance of native plants in their gardens and are leaving plants up over winter, most yards and cities on their own do not provide adequate homes for our beneficial bugs and wildlife. “We have 81 species of native bees in the Bay Area,” says Lisa Lee Benjamin, founder of Urban Hedgerow, and our urban environments do not supply enough habitat opportunities for them to survive. Providing cavities and wood with predrilled holes creates more chances for these essential insects to grow and expand their populations in our urban environments. Constructed habitats for spiders help reduce houseflies and mosquitoes.

You can be an urban-habitat instigator, too. Urban Hedgerow hosts workshops and sells ready-made bug boxes on its website. You can easily build a habitat tailored to your environment too.

Constructed habitats can be easily added to city environments for use by wildlife year-round, particularly important over winter. “Creating habitat, rest stops and food sources for insects and birds helps to encourage biodiversity in our city and beyond,” says Urban Hedgerow project manager Blaze Gonzalez. They also help with garden productivity.

What You’ll Need to Make Your Own Bird and Insect Habitats

Materials:

Habitat hanger: sawtooth hook, magnets, nailsWood rounds deep enough to drill 4 to 6 inches deep Wood perch for bird habitatsPlant materials (leaves, twigs, bark, pine needles, thistle, grass) Hollow stems or reedsWool, horse hair, moss (for birds to build their nests)Twine, cottonTools:

DrillHammerHot-glue gunScissors

1. Find or Create a Shelter

Use discarded wood pieces, fallen branches or large husks. Check with your local parks department or garden center for end cuts and other discarded wood pieces. In fire-prone areas like parts of California, using fallen wood debris in your own backyard can assist with fire prevention.

The wood can be any diameter, but should be deep enough to drill 4 to 6 inches without going all the way through. Avoid any wood that has been treated with a preservative.

2. Add Filling

Look to the landscape for the filling for your habitat. Incorporate branches, bark, lichen and moss, as well as other organic materials like wool, rope, twine and burlap — birds construct and line their nests with these materials.

Urban foragers can look to abandoned lots or fringe landscapes for plant material. Gonzalez gathers dandelions and pellitory (a host plant for West Coast lady butterflies) from street cracks in San Francisco. “Through harvesting things like teasel, fennel and broom branches, we help maintain these so-called weeds at manageable levels,” says Benjamin.

Grass seed heads make good fillers …

… as do bark chips, pine needles and eucalyptus cuttings. Incorporate the plant material you find around you; it’s naturally suited to shelter the bugs and wildlife these habitats are for.

3. Prepare the Habitat

Drill holes in a range of sizes, from ⅜ inch to ¾ inch in diameter and 3 to 6 inches deep, to encourage a a variety of pollinators. Space the holes about ¾ inch apart, center to center.

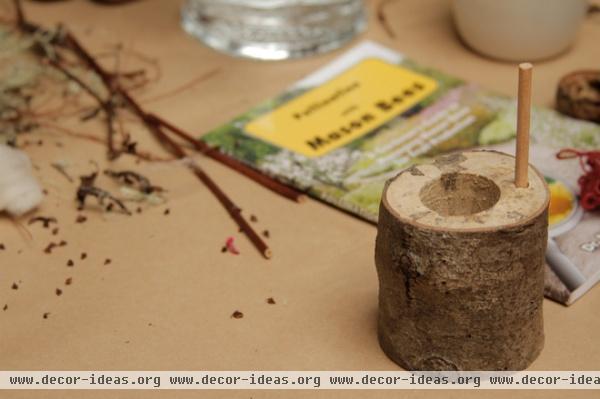

Drill pilot holes 4 to 6 inches deep for mason bees, as shown in the foreground here. Carpenter bees bore deep into the wood for their nests, adding pollen and eggs to six or seven individual compartments.

Add a wood perch for bird habitats. Make the hole size specific to the type of bird nesting in your area; research local birds and drill accordingly.

Encourage a variety of nesting animals by mixing up the materials you include in your habitat. You can glue materials in, tie them on or tightly pack them in. Songbirds like to line their nests with yarn, wool, grass, downy seed heads (like these dandelions) and lichen. Don’t glue materials for bird habitats, which act more like a supply station for their own nests.

Spiders and beetles prefer warm, dry cavities, 3 to 4 inches deep, filled with mulch, leaves, twigs and sawdust. These bugs may not be as cute as birds and bees, but they are essential for keeping the “bad” pests at bay.

These shelters are inspired by the nesting habits of insects and birds, says Gonzalez, not necessarily imitations.

“The habitats are meant to be beautiful objects and serve as altars to take notice of the small creatures we don’t often see but without which we would not survive,” Gonzalez says. “The bugs don’t care how the materials are arranged, just that the materials are there.”

5. Hang It Up

Add a hanger to your habitat — whether a sawtooth hook or a magnet — so you can attach it to the surface you chose.

Place your bug habitat in a sunny, dry location, preferably on a south-facing wall. It’s important that the habitat is protected from the elements, including rain (which can drown the bugs), and that it receives sun to prevent it from becoming a dark, damp place. Hang your habitat near the garden, or not, and enjoy the view.

6. Replenish as Needed

Gonzalez suggests swapping out the organic materials every season, or sooner, as they get used up.

It’s also important to sanitize or clean mason bee holes every couple of years to minimize the buildup of mites and ward off other diseases and pests. Hang a clean bee box next to the existing box and remove the used habitat after the mason bees have emerged for the season. The used habitat can be cleaned with a mild bleach solution. Store it, then reuse it when it’s time to clean out the other bee habitat.

In your own garden, providing a water source and growing native plants that provide nectar and pollen sources for these beneficial insects and wild pollinators can help. Plant for a continuous bloom cycle — including plants that bloom especially early or late in the season.

“We are and will be increasingly living in urban habitats,” says Benjamin. “We tend to think of them very differently than natural habitats, but the reality is, they are just another ecosystem — and one that deserves the same attention.”

Tell us: Are you accommodating the good bugs in your garden? Please share details in the Comments section below.

More: Gardeners Champion Nature’s Cause in the City