New Ways to Think About All That Mulch in the Garden

After four years my neighbor finally put in a modest foundation bed last summer. I watched her laboriously dig out a 3-foot-deep bed, tearing at the fescue imbedded in potter’s clay (that’s our soil). Eventually she put in a row of three evenly spaced barberry shrubs, a miscanthus in one corner and a hosta in the other, then a daylily of some type. She mulched her bed with so many wood chips, they rose halfway up the barberry shrubs and almost covered the daylily leaves.

To be encouraging, I told her how wonderful it all looked, when what I really wanted to say was, “What do you think about staggering those plants? How about a more curved bed? Maybe that miscanthus won’t work so well in that much shade.” But most of all I wanted to point out that her plants were drowning in mulch.

I couldn’t say any of this — I feel bad talking about it now, like I’m some sort of landscape backseat driving jerk for even mentioning my thoughts. It’s her house, her yard, her plants. But the mulch. The mulch. So instead of talking to my neighbor, I’ll talk to you about why wood mulch can be both great and, well, not very great at all — and what a better alternative might be.

Types of wood mulch. We’ve been taught that wood mulch is essential, and in a lot of ways it is. If you use it, chunky wood mulch at a depth of 3 to 4 inches is best at suppressing weeds and adding organic matter to the soil, while also allowing good water infiltration. Finely shredded wood mulch tends to create a dense, impermeable mat and even blow away, but it’s great at weed suppression. The point here is that the kind of wood mulch you use matters. And don’t use cypress, as it’s often harvested unsustainably (of course, it wouldn’t surprise me if all wood mulch is harvested unethically).

Wood mulch is good for your soil. Termites don’t like wood mulch, contrary to the myth my home builder told me when he saw I was putting it right up against the house. It also doesn’t suck nitrogen out of the soil as it decomposes; instead it creates awesome soil by encouraging microbial life.

Yes, this was my garden many years ago, with 20 yards of mulch and when I was clueless about everything. Please note that I now mulch it with the perennial stems I cut down each spring, which isn’t enough, but it doesn’t matter — by early June you can’t even see the ground.

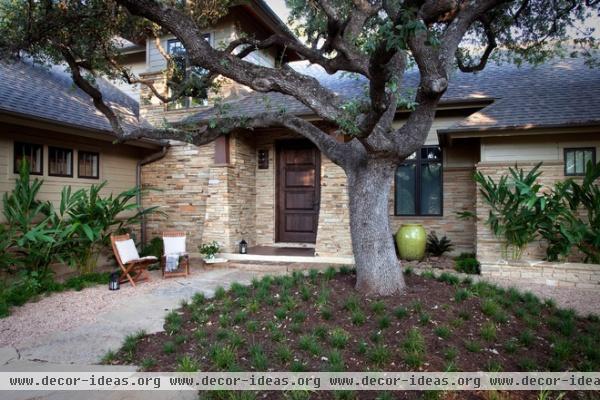

But too much is very bad for plants. Let’s also talk about mulch volcanoes. You know, mountains of mulch piled up 1 foot to 2 feet against a tree trunk. I never knew my city was riding over a fault line filled with mulch magma, but apparently it is. This practice will lead to disease and trunk rot and tree death. Personally, I prefer the park-like look of trees with no mulch — trunks coming straight out of the lawn or meadow, like the olive tree and mass of lavender here. Trees like river birch even seem to prefer plants around their root zone, which better shade and cool the soil.

All that being said, some studies show that a circle of mulch around trees and shrubs increases their rate of establishment and growth over the years. How’s that for conflicting info about mulch? Keep in mind, though, that a tree’s feeder roots will eventually reach out to at least twice the tree’s height — that’s one really big potential mulch circle.

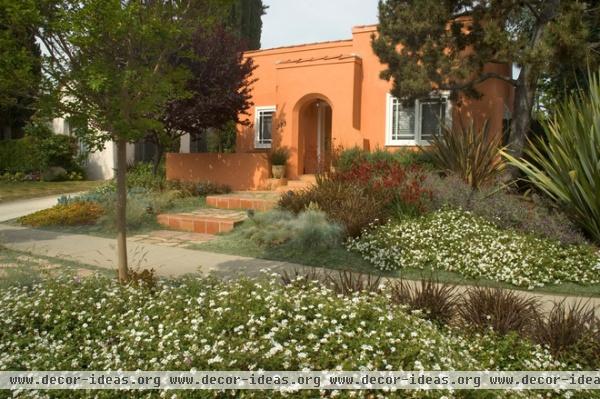

Wood mulch maybe isn’t the best mulch. Designwise, I feel that mulch maroons plants and makes a perennial bed look like every other perennial bed. Mulch is default landscaping, and it kind of bugs me, as it’s very boring. If you can’t afford more plants, buy plugs, which are often a third the price of larger pots and give you more plants for your buck. In a worst-case scenario, plugs establish and spread just as fast as much larger root-bound nursery pots. More plants. More awesome.

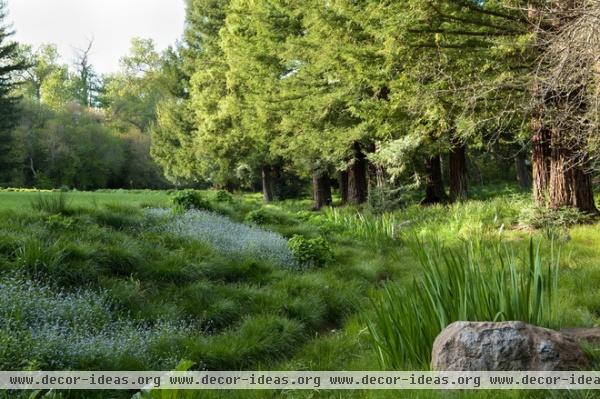

Plants are the best mulch. Why not let your self-sowing perennials self-sow? Let them spread, get free plants, create a dense garden full of life and shelter and food for insects and birds and spiders and frogs and kids. Nature abhors a vacuum, and mulch is a vacuum devoid of life. In nature smaller plants and seedlings are the mulch, in effect. So if you’re actively planting a new bed from scratch, consider what shorter plant to use in front and under taller ones to create a rich, beautiful layer that serves many purposes at once.

Eventually you won’t even need mulch. After a few years, as your plants establish, you won’t really need any kind of trucked-in mulch. The taller and thicker plants create a shade barrier to most weeds and help conserve soil moisture. If anything, I’d say top-dress with some nice compost in the fall, since compost can be both a mulch and a natural fertilizer. Letting it soak in over winter is also a smart idea.

One last reason plants make a better mulch. In a sunny area, you have to keep adding mulch, maybe as often as once a year, because mulch breaks down faster in sunlight. That’s not as low maintenance as I like, but wood mulch is far better than rubber (adds nothing to the soil; seems sort of like pollution) or rock (adds nothing to the soil; pain in the derriere to clean debris from or dig in). Nothing mulches like a nice plant ground cover and a diverse, vastly more interesting and layered perennial bed.

So there you go. As always, I’d like to hear about your mulch experiences, expert or not. Mulch can be a complex topic, depending on where you’re located, what kind of soil and climate you have, what the drainage is like etc. Maybe we can create a database of sorts? Happy mulching (or not).

More: Lessons in the Rewards of Selfless Gardening