Spring Garden Ideas From Colonial Williamsburg

You can step back in time in Colonial Williamsburg, an interactive living history site that served as the capital of the Virginia Colony from 1699 to 1780. Named in honor of William III, King of England, and designed by Royal Governor Francis Nicholson, Williamsburg is one of the country’s oldest planned communities. Restored by John D. Rockefeller, Jr., over many years beginning in the 1920s, the historic area is a great place to learn about 18th-century life — including how people gardened.

Grab a cup of coffee from R. Charlton’s Coffeehouse (billed as America’s only 18th-century coffeehouse) and explore on foot. Wander down lanes or thoroughfares bustling with wagons, marching bands and tradespeople dressed in authentic garb; peer over fences to look at vegetable or flower gardens that showcase early-American plants. The homes and plots are small by today’s standards, but you can see how every part of a property was used, and for homeowners with similarly modest lots, it’s inspiring to see such thrift and practicality on display.

Here are just a few design ideas I came away with on a recent visit.

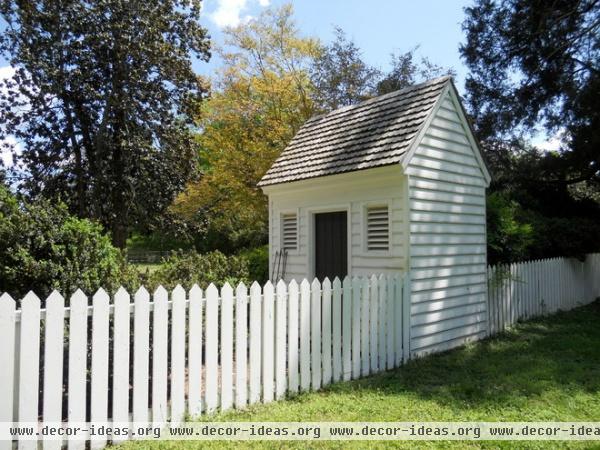

Fences make good neighbors. When you’ve got a small cottage or outbuilding such as this, a fence that’s scaled in proportion to the building is easy on the eye. It also delineates property lines, keeps livestock out and keeps some livestock, like chickens, in.

Here’s a different fence that suits a much more formal home — stylized panels evoke an ordered landscape of geometric beds or French parterres. A detailed fence like this needs little ornamentation, and its open design allows passersby to look through.

Just one or two of these panels would look fantastic in a townhouse entry garden; you could also create a similar trellis for a small patio wall.

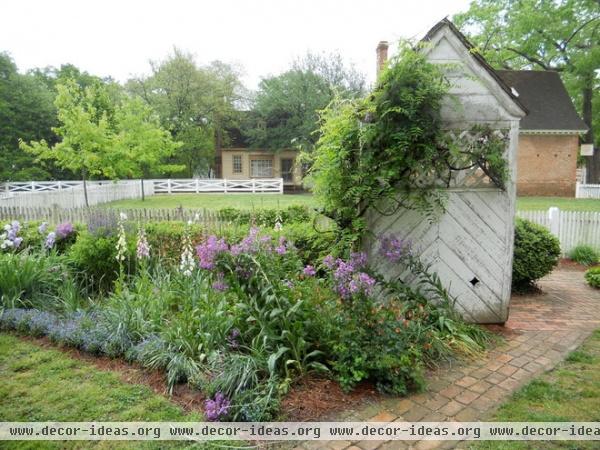

This fence runs directly into a structure, which is unusual (perhaps it’s built on the property line), but I love the composition. The slatted fence is plain, in keeping with the white shed.

Make outbuildings both functional and beautiful. I wasn’t expecting to see so many great sheds in Colonial Williamsburg, and I came away with a desire to add something to my vegetable garden so I wouldn’t be hauling tools in and out of the garage every day.

Wouldn’t it be great to have a proper toolshed in which to stash rakes and shovels, and store clay pots over the winter?

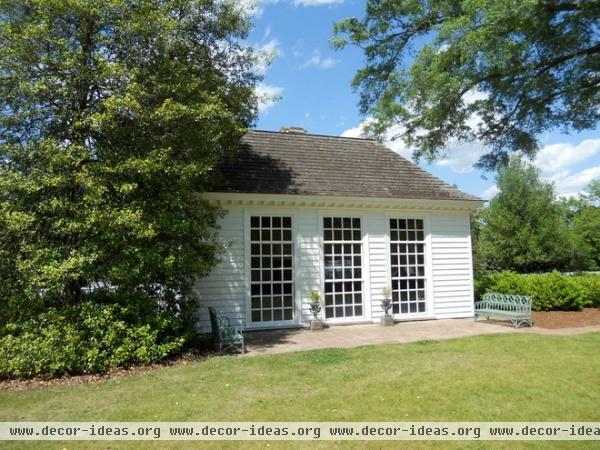

This is a teahouse at the Rockefellers’ home, Bassett Hall. Presumably used for afternoon entertaining during the spring months when the family was in residence, it’s the kind of building that could be used for summer soirees, too.

Flanked with benches and minimalist plantings, it’s a focal point as one wanders around on the grounds. I want one of these, too.

You can grow ornamental vines on sheds to create a layered garden, creating a sense of informality and a touch of romance. Let climbing vines like clematis, honeysuckle, wisteria or roses soften the look of an older structure that’s seen better days. (If your shed is wood, you’ll have to remove vines in order to paint, which is easier said than done.)

Let benches provide a shady place to rest out of the hot sun. In a walled enclosure like this, position benches near shade trees so that you have a place to sit and view the garden in relative comfort. In this formal garden at the Governor’s Palace, brick edging defines the beds and surrounds a decorative bench — a calming composition.

Leafy bowers can be playful and fun. What’s a bower, you ask? It’s a shelter or covered place in a garden made with boughs or vines wrapped together — a shady recess. This enchanting green tunnel is just that — presumably where the ladies of the house might saunter and take the air, hidden from view. One can imagine secrets being exchanged in such a place.

These days it’s easy to replicate the look with metal arches and climbing vines, like roses or honeysuckle.

Another bower tucked away off a back lane is made with the branches of hornbeam trees, trained to arch over a pathway. This is a much more involved project, and not to be undertaken if one is looking for quick results.

Simple tunnels can be fashioned out of living willow, which is very fast growing and will give the same effect on a smaller scale — perfect for children’s gardens.

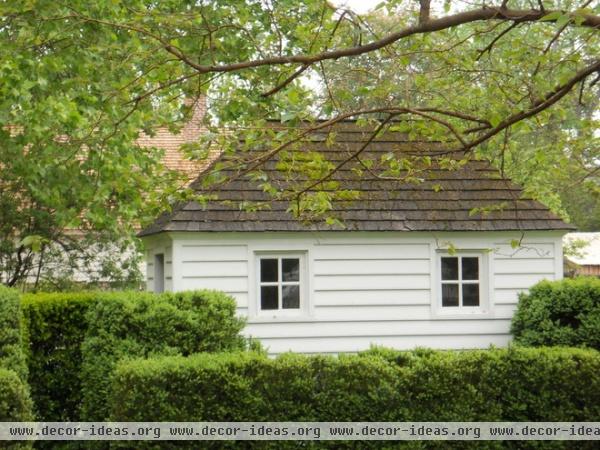

Edge gardens with boxwood for year-round good looks. Clipped boxwood can be simple or stylized. Used here as a hedge and cut to varying heights, it creates enclosure while framing the structure in a simple, elegant way.

For those without a lot of time to devote to gardening, using boxwood as a primary landscape plant will give you a classic foundation that doesn’t require a lot of upkeep (save for the shearing).

Make garden entrances interesting with border plantings. Who doesn’t love foxgloves in the flush of early spring? This picket fence and entry gate are softened by the informal planting of lush pink blooms — impossible to miss as you pass through the gate.

Fenced gardens are so much more interesting when there are unusual or scented plants located near the entry path.

Repurpose old bricks. I love the patina and character of old bricks and was heartened to see so many used in the pathways around the historic area. Brick is a traditional building material and can be quite formal when used to make a garden walk, but you can experiment with patterns and make the look less formal.

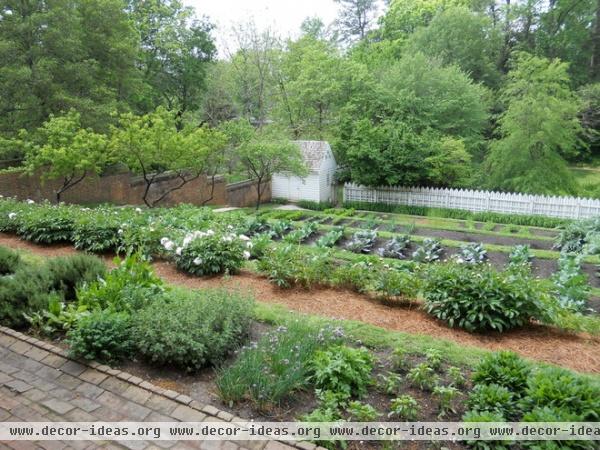

Add perennials to vegetable beds. The Governor’s House has one of the most beautiful kitchen gardens I’ve seen, with terraced slopes edged with brick paths and pine mulch, and neatly hoed linear beds with peony clumps scattered about.

Some great flowering plants used during the colonial period include cornflowers, flax, calendula, baptisia, love-in-a-mist (Nigella damascena) and hyssop. All of these will help bring in the bees, too.

Use tall plants in mixed borders for drama and vertical interest. A knockout combination of stately foxgloves (Digitalis purpurea), purple barberry and cottage pinks make a visually stunning spring planting. If you like the unusual, foxgloves will put on a show that lasts for a while, and the taller forms can be very effective in groups.

Foxgloves are the perfect pick for a cottage garden or a more stylized perennial garden with formal outlines, as shown here.

Other tall early-American plants grown in the gardens here include castor bean, China aster (Callistephus chinensis), crested cockscomb (Celosia argentea var. cristata) and larkspur.

Choose local, budget-friendly materials for pathways. Virginia’s tidewater country is home to oysters; colonials made use of crushed shells for roadways and paths. Today they’re still used in many areas just as they were centuries ago, and they make an inexpensive material.

Grow more herbs and vegetables at home. In the olden days, people used plant remedies as cures for everything from fever to infertility. If you’ve got a sunny garden with well-drained soil, think about adding rosemary, thyme or lavender in dry areas; grow peppermint in pots (to contain the roots) and make your own tea infusions. Make this the year to experiment with new herbs and kitchen staples like onions, garlic, spinach or cabbage.

Visit Colonial Williamsburg: A visit to the garden and nursery will give you a look at the many plants grown during the 18th century. The 68th Garden Symposium at Colonial Williamsburg, cosponsored by The American Horticultural Society and Organic Gardening magazine, takes place April 5, 2014.

If you can’t make this year’s symposium, follow the blog by head gardener Wesley Greene, who posts about the colonial garden. You can learn a lot from Wesley’s posts, which include historical snippets from old gardening calendars and journals. You can also get the recently published book Vegetable Gardening the Colonial Williamsburg Way to learn more about growing heirlooms.

More: Vegetables and Flowers Mix in Beautiful Edible Gardens