Curtain Speech

http://decor-ideas.org 03/21/2014 22:22 Decor Ideas

Have you ever heard an interior designer talking about draperies and wondered if he or she was speaking in a foreign tongue? Terms like “jabot,” “swag,” “goblet pleat,” “inner lining,” “tieback,” “fullness ratio,” “return,” “stack” and “puddle” are enough to make your head spin. Never fear: If you become familiar with a few of the basic terms, you’ll not only be able to understand your interior designer better, but you’ll be better equipped to articulate what you like and don’t like about window treatments.

Is there a difference between curtains and drapes? Arguably, yes. Curtains tend to be lighter and less formal, like bathroom curtains or kitchen curtains. They are also generally window length rather than full length, and are not lined.

Café curtains like these exemplify the light, airy, informal feel of curtains. A café curtain covers only a portion of a window — usually the bottom two-thirds. It is the perfect application when you want a simple treatment that allows a lot of light, and when all of the window does not need to be covered for privacy.

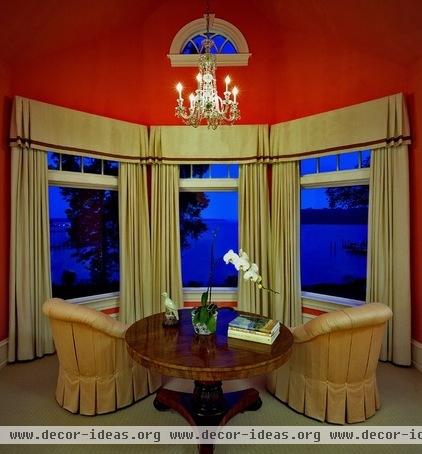

These, on the other hand, are drapes. Floor length, more formal, more gravitas. Drapes like these are almost always lined, and are sometimes inner lined as well. That extra lining inside the drape is often a lightweight flannel. Not only does it give the fabric a lovely “drape,” but it’s a great insulator when the panels are closed. Drapes can be operative, which means they open and close, or stationary, which mean they do not move and are decorative only.

Now we enter the world of top treatments. Swags and jabots are at the other end of the spectrum from curtains: They are inherently and irrevocably formal in feel. The horizontal portion that swoops across the top is the swag, and the complex pleated portion trailing down the sides is the jabot.

“Jabot” is a dressmaker’s term originally describing a ruffle attached to the front of a man’s or woman’s shirt. Jabots are often lined with a contrasting fabric, which is revealed along the bottom edge with each pleat.

Proportion is especially critical in these treatments, but that subject demands an ideabook of its own.

Valances are most often specified when you want to hide the drapery hardware used to make your treatment operable. Valances usually hang freely from a hidden board or rod, and can be flat, gathered, ruched or shaped; the options are almost infinite.

If you love valances but don’t want to draw your draperies, no problem: They can be strictly decorative.

A cornice is a valance’s kissin’ cousin. The only real difference is that a cornice is hard rather than soft. It usually consists of fabric upholstered onto a padded (sometimes shaped) board. It makes very economical use of the textile, in that it is not gathered or pleated, but is tightly stretched.

If you have fallen in love with a very expensive fabric, a cornice can make it more affordable. Also, because the fabric is stretched, the entire pattern is revealed.

Curtains are usually gathered or pleated in some way, but did you know that there is a whole subcategory of vocabulary to describe the choices available? A tab-top drape or curtain has a loop of fabric used to attach the panel to the rod. These can be very handsome but are not a good choice if you want to draw your draperies across the window. Trying to make the tabs slide well together is like trying to herd cats.

A rod pocket is another way to attach a drapery panel to the rod. Quite simply, there’s a pocket at the top of the panel that the rod is slipped through, and the panel is gathered on the rod.

Again, this is best used when the drape will be stationary rather than operable, unless your idea of a good time is standing on a chair and pushing fabric along a rod.

Then there is the plethora of pleat options. The pleat is used to gather the entire width of fabric into a manageable width at the top, where the panel meets the hardware, providing your drapes with a beautiful fullness. Pleats can be attached with rings to a rod, or with hidden drapery hooks that connect to traverse hardware. “Traverse” (with the emphasis on the first syllable) means that the curtain can actually be drawn across the window; a curtain can also traverse (emphasis on the second syllable) the window. Three-finger pinch pleats like these are the most common …

… whether used on rods or traverse hardware. A pinch pleat is usually tacked (stitched) only at its bottom …

… while the French pleat is tacked only at the top …

… and the goblet pleat is tacked at the bottom, but not gathered into fingers. The resulting goblets are usually filled with batting to hold their shape. (Do you ever wonder who thought this all up?)

The box pleat forms a little box at the top (think of an old-fashioned box-pleated skirt). I like to use this pleat in studies or dens, as it brings a more masculine look to the treatment and works very well with linear or plaid fabrics.

The pencil pleat is a set of folds at the top of a curtain that look like a series of vertical pencils. Normally they are approximately 3 inches long, but again, it all depends on the proportion.

A tieback is a piece that ties back the curtain or drapery (duh). It serves multiple functions, including …

… holding back the curtain from the window to admit more light when the drapery is not needed for privacy. A tieback provides a way to open your curtain when there is no traverse rod.

Tiebacks are also a style choice. If you do not like the look of a panel hanging straight down, a tieback is for you.

Just as there are many choices for pleats, there are several choices for the overall length of your treatment, and just as many terms for those lengths.

If your panel is stationary, there are two good choices for length: puddle or trouser break. These gorgeous, formal panels cascade with a flourish of fabric onto the floor, forming a puddle. A puddle-length panel trails a minimum of 6 inches onto the floor and could be much longer, depending on how extravagant you are feeling.

These panels are trouser-break length. See how they collapse just lightly onto the floor, much like a nicely tailored man’s pant just breaks onto his shoe. When creating your window treatment, nothing (well, almost nothing) is more detrimental to the look of the finished product than making your panels too short.

If draperies — like these sheers — are going to traverse the window, neither puddle nor trouser break is right. You don’t want your fabric dusting the floor every time it opens and closes. Operative panels should just barely graze the floor — long enough to look like they are touching but actually a fraction shorter than that. Again, avoid high-water draperies like the plague.

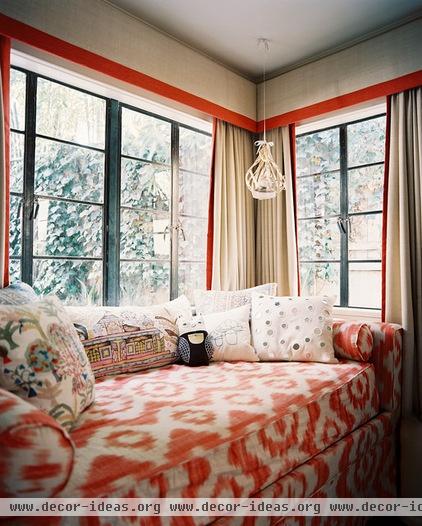

In the interests of full disclosure, you should know that I absolutely abhor curtains whose length stops at or just below the window sill. I gag at the mere prospect, except in cases like this, where that length is just perfect. If your window treatment is over a bathtub, a kitchen sink or a window seat, this length is completely appropriate.

While this has certainly not been an exhaustive study of window treatment terms, it’s a good start. If you are still with me, you might be wondering how to decide between stationary or draw curtains. Excellent question, and one that I will tackle in the next ideabook, where we will add to our window treatment vocabulary.

More: 12 Great Decorative Alternatives to Curtains

Coming next: The case for curtains that never close

Related Articles Recommended