Houzz Tour: From Doghouse to Contemporary Gem

When architect Jeff Sherman found this row house in the Prospect Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, it had gone to the dogs. The previous owner, who had grown up there, had rented it out for a number of years. When it became uninhabitable, he used it to breed Cane Corso dogs — huge, muscular mastiffs.

When the property went up for sale, it was in such poor shape that the broker refused to show it. That task fell to the owner, and before he allowed Sherman inside, he had to chase the canines into the backyard and lock the door. Against all odds the architect, who’s with Delson or Sherman Architects, thought the house was just what he was looking for, although it was falling down and unspeakably dirty. (His contract included a stipulation that all of the dog waste had to be shoveled out.) “I knew I wanted a building, not a condo or apartment, and I knew that I wanted to make significant architectural moves,” he says. “I also needed to buy something that cost very little money, so this house fit the bill.”

Houzz at a Glance

Who lives here: Jeff Sherman

Location: Prospect Heights, Brooklyn

Size: 2,500 square feet (232 square meters)

There are two units. Sherman inhabits the upper two-story dwelling, which has two bedrooms and two baths, and rents out the lower one-bedroom, one-bath unit.

The brick row house was built at the turn of the 20th century. When Sherman bought it the floors were caving in and the stoop had collapsed. “I purchased it in 2000, and the neighborhood was rough, but there were a lot of nice areas around it,” he says. “I thought it would be a matter of time before this area improved, and I was right.” Sherman completed the remodel in 2010.

Sherman’s big idea was to carve out the center of the house, creating a double-height volume that, thanks to a long skylight, acts as a light well for the formerly dark space.

The thick copper-clad wall at the entry also has a space carved out of the center — it acts as a bench for removing shoes. “I used copper because I wanted this dividing wall to read as a two-story object,” he says. (It reappears on the second story in the guest room.) “I also knew I could apply it myself, and I like how it reacted to the human touch, growing shiny over time where it is handled.” The ceiling is made of inexpensive cedar, the kind usually used to line closets. “It smells wonderful,” Sherman says.

Gray painted wood, salvaged from the house during demolition, brackets metal pieces and acts as support beams. “It was cheaper to leave the beams visible, so I made them a statement,” he says.

A dining room table sits in the middle of the open area, and the kitchen is to one side. The chalkboard-covered cube has a translucent door (to a pantry) and an opaque door (to a powder room).

The master bedroom, directly over the kitchen, is kept private by two layers of a corrugated plastic, the kind that’s usually used as roofing. “One layer just didn’t provide enough privacy, so I added another,” says Sherman.

The rear wall of the home is covered by a thin layer of concrete. It was simply troweled over a damaged-beyond-repair masonry wall and scored with lines (a technique call parging) to keep it from cracking. The sun playing over the stone-like surface looks dramatic. “It looks kind of like a church,” says the architect.

The open shelves above and to the right of the table act as the rear wall of the bedroom. “I was going to cover the back of the shelves with something, but I couldn’t stand to do it once they went up,” says Sherman.

The stair rail and pressed-tin wainscoting are original to the house. “The stair treads were too damaged to save,” says Sherman. “But luckily that pressed-tin pattern is still being manufactured, so I was able to repair and restore it.”

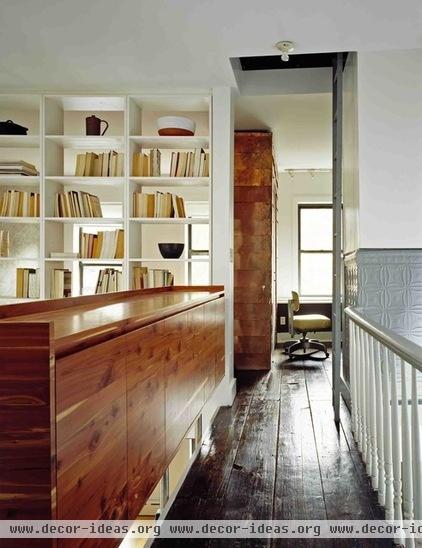

On the upper level, the architect designed a catwalk that runs between the two bedrooms. A row of built-in cabinets divides it from the lower story.

Echoing the ceiling on the first floor, the cabinets are also crafted from knotty cedar.

The original floor on this level was able to be saved, “although I had to pull many, many staples out of it when I pulled up the carpet,” says Sherman.

Like the dining room wall, the wall behind the headboard is covered in troweled concrete. The wall around the window is lined with large cabinets that serve as a closet. This makes the space around the window deep enough for a window seat.

The upstairs bathroom is small, so Sherman made it a wet room — a waterproof room where the entire space is the shower.

He left a window (the lower half is obscured) and tiled the floor with brick (a long drain is located under the window), because he wanted the space to feel like an outdoor shower. “I’ve always wanted one but can’t have one in the city,” he says. “I just made it feel like it’s outside.”

The chance to have real outdoor spaces helped lure the architect from Manhattan to Brooklyn. A deck that opens off the kitchen has a table and a brick-lined fire pit.

The partially trellised yard (the trellis supports prolific vines with Concord grapes) is filled with green. “I wanted it to be incredibly lush,” says Sherman. “One of the surprising pleasures of the house is that I love gardening — I never expected to like it as much as I do.”