Gardening for the Bees, and Why It’s a Good Thing

I stopped gardening for myself years ago. It probably happened about the time I saw a bumblebee pulling itself along the ground one fall morning; once it crossed from shade into light, it stopped, seeming to lay out as if on a beach. After I spent a few minutes watching and waiting, the bee finally took off, perhaps to the last of the asters or to a place with no gardener who has a staring problem. Since then I’ve had my face so far into blooms that I’ve felt the turbulence of a bee’s wings tickle my peach fuzz — I even once found a bee hanging on to my jeans (it must have been on me for hours as I walked around the house and sat on the couch).

Insects are the base of life. Ninety-six percent of songbirds feed them to their young, and songbird populations are in decline. Insects pollinate 75 percent of our food. Bumblebees are vanishing at an alarming rate due primarily to habitat loss, but now a recent study shows that honeybees may also be giving the bumblebees debilitating diseases. And what about the other 4,000 native bee species? What about butterflies and dragonflies and moths? So I’ve stopped gardening for myself, and it has made my garden designs better. Clients and I are becoming more aware of natural functions, of place and region, and are celebrating the fourth dimension of a garden — that airspace above, so full of life essential to our world. How can we not garden with and for the bees?

Meet some native bees. Bees come in all shapes and sizes, and many are specialists that single-flower species depend on to reproduce. In fact, native bees exhibit floral fidelity — when one species is in bloom, they will forage only on that species. This fidelity increases the flower’s genetic pool and seed production. When these native specialist bees aren’t around, generalists take over; they don’t show floral fidelity, resulting in fewer seeds.

Don’t fear the buzz. There are lots of cultural fears and myths about bees. The biggest one is that they are out to sting you. Nothing could be further from the truth. Sure, it took me — and even still takes me — time to calm my nerves when the garden is taking off around me in a symphony of buzzing. But native bees are almost all solitary, making them hesitant to sting, as there’s no hive to defend. Many native bees don’t even have stingers.

They’re better pollinators. Many of our charming native bees are cavity nesters. This bundle of Joe Pye Weed stems is perfect for bees like the blue orchard mason bee, who in late summer lays an egg with a pollen cache, seals off a cell, makes another cell with egg and pollen, and so on. Over winter the larvae emerge, and in spring the bees emerge. Native bees are some of the first and last pollinators — think about bumblebees who heat up in sunlight or buzz themselves warm just like we do when we shiver. If you have early- or late-season vegetable crops, you’ll want more native bee species around to increase yield.

Leave wild habitats. Lots of bees nest in the ground, so leave some bare spots. If the soil is especially loose — like sand or gravel — it may be even more appealing. Brush piles and holes in dead trees are all potential nest sites. It should go without saying that whenever you or neighbors are spraying pesticides and other chemicals, you’re hurting bees.

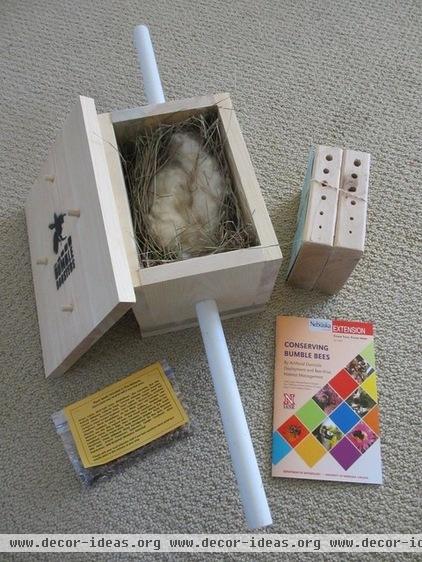

Add constructed habitats. Here’s a bumblebee house I picked up from Bumble Boosters, a program at the University of Nebraska to test domicile designs. You can place it on the ground covered in brush or mount it off the ground, depending on which species of bumblebee you’re hoping to attract. If you place it on the ground, you insert two PVC pipes that are used as tunnel entrances. Of course, the best thing you can do is have a slightly messy garden — a corner with brush piles, an unraked area, a dead tree etc.

Plant native plants for native bees. Native plants and native bees are in evolutionary sync. Even with climate change, it seems evident that as flowers bloom earlier, the insects are keeping pace — but not the birds. Climate zones are moving north at 3.8 feet per day, but we can hedge our bets by using regional native plants, not only for weather adaptability but to support local pollinators and bees, who know those native plants best.

See how to grow plants native to your region:

Northwest | California | Southwest | Texas | Rocky Mountains

Central Plains | Great Lakes | Northeast | Mid-Atlantic | Southeast

Native bees are essential to our species. Through pollination they provide billions of dollars’ worth of free services to our food supply. Through floral fidelity, evolutionary sync and specialized strategies like buzz pollination, they are better than nonnative honeybees, who are already overstressed and overworked. By gardening for bees and other pollinating insects, we ensure our health and the health of the landscape beyond the garden fence. Why would you garden any other way?

More: Garden for Wildlife to Reap Rich Rewards