Houzz Tour: Seeing the Light in a Sydney Terrace House

http://decor-ideas.org 02/18/2014 05:23 Decor Ideas

Walls make a room, but this row house in Sydney’s Bondi Beach neighborhood shows how light and framed views define a space.

When architect Matt Fearns of Fearns Studio was confronted with a lack of privacy and natural light in a narrow Victorian terrace house, he resolved both issues by confining most sources of natural light to the ceilings. Like moths to a flame, in this house you can’t help but go toward the light.

Houzz at a Glance

Who lives here: A young man who shares his home with friends and flatmates

Location: Bondi Beach neighborhood of Sydney

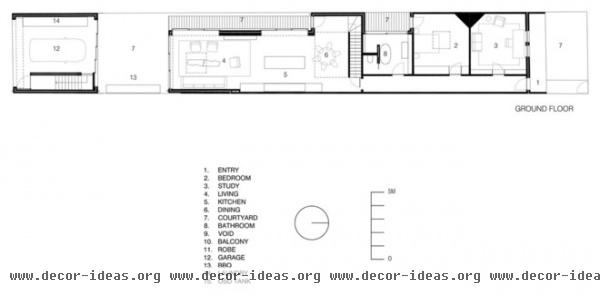

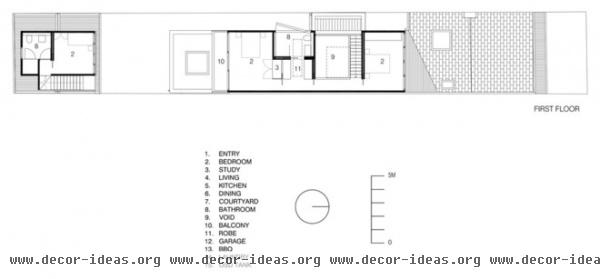

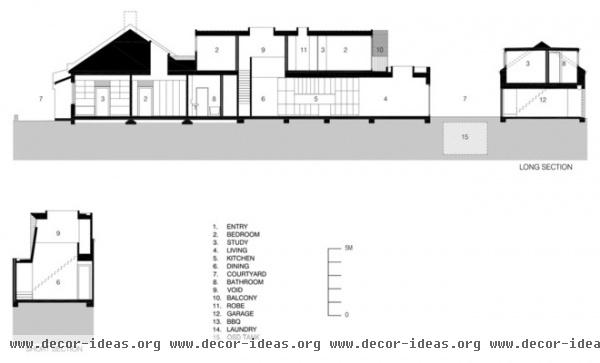

Size: 2,800 square feet (260 square meters); the lot is about 20 by 139 feet (6 by 42½ meters)

Year remodeled: 2012; originally built in 1890

Photography by Tom Ferguson

The home was built in 1890, and various remodels were done over the years. It’s one house in a row of four. As it sits on a 20-foot-wide lot, it’s apparent that privacy — for both the homeowner and the neighbors — was a primary issue.

The back deck, shown here, projects off the master bedroom.

Fearns resolved privacy by designing the home like a tube. “The purpose of the tube idea was simply to direct views from the house away from neighboring properties by placing openings only at the ends,” he says. “I wanted to leave the side elevations largely clear of windows to declutter them, as well as eliminate the overlooking impacts.”

Though this was primarily a contemporary renovation, the home shows its age through subtle details like this archway and the baseboards.

Fearns brought sunlight to central areas of the first floor with multiple skylights. The natural light works as a push-pull tool: the dark, compressed hallway pushes you toward the glowing light at the end of the tunnel. (Or the light pulls you toward it, depending on your outlook.)

In the dining-kitchen area, the void (as Fearns calls it) brings light from the roof down to the first floor. The skylight is roughly the size of a queen bed and is central to the design of the house. In addition to illuminating the space, the light creates permeable boundaries that define the eating space within the open floor plan.

Vintage dining chairs by Australian American sculptor Clement Meadmore and a vintage dining table by Alessandro Albrizzi disrupt the otherwise linear language of the kitchen.

The dining area connects to the kitchen — the heart of the house, as Fearns calls it. “It’s set between the lounge and dining areas to be a hub for both,” he says. Though oversize and solidly built, the Tasmanian oak island and cabinets inhabit the room, rather than dominating it. Fearns detailed the kitchen features to “look like items sitting in the space, rather than elements which the space has been built around,” he says.

Pendant lights: Smithfield S Pendant Light, Flos; wire bar stools: vintage Clement Meadmore

The living area rounds out the great room. It can be difficult to create intimate spaces in open plans, but Fearns employed various techniques to bring the home down to human scale. “In this case the rhythm of solids and voids [walls and glazing] primarily helps create a sense of smaller spaces within the open plan,” he explains. The walls and door frame various areas of the great room, suggesting how to furnish and lay out the space.

The materials and finishes developed as the project progressed. “The palette in the end was limited and simple and comprised mainly [of] clear sealed hardwood doors, windows, flooring and joinery — almost all Tasmanian oak with some blackbutt,” Fearns says. Polished concrete floors connect all the spaces in the great room.

Deep door frames capture exterior moments like paintings. Light and shadow play animates the bare walls.

The ground level is broken up into various zones that can be opened or closed off to maximize flow, while always maintaining strong visual connections between spaces. “When doors are open, the rear portion of the site effectively can become a single open space — albeit modulated by various smaller areas within it,” Fearns says. A skylight directs more sunlight into the living room.

Coffee tables: vintage Paul Kafka; sofa: Jetset Lounge, Very Tidy; rug: Turkish kilim

A garage and guesthouse loft are nestled into the back of the lot. Tasmanian oak doors slide open, connecting the garage, landscape and main house seamlessly. The same polished concrete floors used in the main house continue in the garage.

The sliding doors in the main living room are hardwood, with bottom rolling hardware and low-e glazing. “The reveals are about 2½ feet deep on the side elevation, because the doors are mounted externally,” Fearns says.

A narrow deck runs much of the length of the house.

Smaller rooms on the first floor open up onto the deck, including this bathroom. The sliding glass door provides natural light and an outdoor connection. (This part of the path is closed off and private.)

Sink: Duravit; freestanding bathtub: quartz, Villeroy & Boch; wall tile: honed basalt

The master bedroom and bathroom are upstairs.

Unlke the first-floor bathroom, the master bath couldn’t have a sliding glass door to connect it to outside. “I didn’t want a window there to keep the side clear, so I convinced the owner to have a hatch,” says Fearns. After trying out various mechanisms, they ended up using a heavy floor-spring pivot that works like a friction hinge.

With the natural light from the skylight, the pivot window isn’t necessary, but Fearns has discovered its other charms. “From the bathroom it also manages to frame a very small view of mature planting on the rear lane, so it’s a nice space to use,” he says. It also “adds a sense of oddity to the side elevation. People have to look twice to figure out what it’s doing.”

More: 10 Statement-Making Skylights, Big and Small

Related Articles Recommended