Updated Woodstoves Keep Home Fires Burning

It’s no surprise that the cultures of cold climates have produced some of the greatest innovations in heating technology. With forests blanketed in snow for months at a time, the countries of Northern Europe have led the way in designs and technologies related to the burning of wood.

The trend toward the use of renewable biomass energy sources has meant a new embrace of a time-tested heat source, the woodstove. Advances in ceramic glass technology have brought stove fireboxes to our living spaces with flames in clear view, radiating both light and warmth. Used intermittently as a secondary or backup heat source, woodstoves pay for themselves quickly during a power outage or an unplanned visit from the polar vortex.

Combustion technology has advanced to the point where many modern woodstoves are carbon neutral. That is, they emit an amount of carbon dioxide equal to that of a log naturally decomposing. This boost in efficiency also means it takes less wood to heat the same square footage. Less wood means less handling, splitting, transporting, stacking and ash removal. Wood is now more cost effective than ever. But before you start splitting and stacking your wood, here are few things to think about.

Woodstove Materials

Woodstoves are made of one of two primary materials: cast iron or steel.

Steel stoves heat up (and cool down) more quickly than cast iron. They’re also less expensive to fabricate and lighter, and can usually be placed closer to wall finishes, because they often utilize shell-within-shell construction — an outer steel shell or cowling combined with an inner steel firebox.

Unlike with their cast iron counterparts, steel stove components are welded together, creating a permanent joint that requires no maintenance. However, this also means that replacing a damaged component isn’t possible. To temper the variable heat that a steel stove provides, some manufacturers offer lay-in soapstone panels whose mass and physical properties allow it to absorb and radiate heat over a longer period.

Pros: Radiates heat quickly; low maintenance; modern styling; durable; cost effective.

Cons: Heat dissipates quickly; limited color options; welded components can’t be replaced.

Cast iron stoves are generally more expensive, because of the complexity involved in the manufacturing process. But they are subject to less variation in temperature than steel and thus provide a more even heat. They take quite a bit longer to come up to temperature than steel stoves of the same size, but they also hold and radiate heat longer.

The casting process allows for more detailed ornamentation, and cast iron can be enameled and thus offers a broader range of colors than steel stoves. Because cast iron can’t be welded, these stoves must be mechanically fastened together, with gaskets and furnace cement. Over time cast iron stoves require maintenance to prevent air infiltration at these joints, which can cause improper combustion. Overfiring is a real possibility if this maintenance isn’t performed. One side benefit to the bolt-together construction is the ease of replacement if a part becomes damaged.

Pros: Even, prolonged heat; decorative classic design; replaceable components.

Cons: Long heat-up times; heavy weight; higher maintenance; higher price.

Choosing between steel and cast iron often comes down to economics. Given the same funds, purchasing a steel stove will often net a better overall value, because purchasing a low-end cast iron stove can mean sacrificing construction quality, which can make for a poor experience over the life of the stove.

Output Size

One of the most important considerations when selecting a woodstove is size. This applies to both the size of the space you’re intending to heat with the stove, and the firebox or chamber that you fill with wood.

All manufacturers offer heating performance guidelines, which are usually tied to square footage. This square footage number is generic in that it assumes 8-foot ceilings, but you can easily translate that to cubic footage to more closely approximate your home’s size.

Heat delivered is shown in a range and represented in BTUs, or British thermal units. The range represents the amount of heat delivered over the entire firing cycle of the stove, from initial to final burn. The average BTU output, the middle of the range, is what you should pay attention to, as firing the stove on the high end will cause undue wear on both the stove internals and the flue.

Knowing your climate zone and your house size and configuration can get you very close to determining the size of stove you’ll need. Follow the stove manufacturer’s guidelines and if possible consult with a local woodstove supplier — they are invaluable resources. Oversizing or undersizing your stove will ultimately mean you’ll use it less often.

Firebox Size

Generically, woodstoves come in three sizes: small (less than 2 cubic feet), medium (2 to 3 three cubic feet) and large (more than 3 cubic feet). Each size can be roughly matched to the size of space you’re heating.

A small stove will heat a single room; a medium one, an average-size, energy-efficient home; and a large stove, a larger or less energy-efficient home. Obviously this is a rough approximation, and room layout will play a role as well. Open spaces are easier to heat this way than compartmentalized spaces, which will require convective flow or circulation of the heated air to have effective heat.

Firebox size is directly tied to the size of logs you’ll be able to use. The standard wood log length is 16 inches, but wood can commonly be sourced in 18- to 24-inch lengths (or splits) as well. This is a particularly important thing to pay attention to, as log sizes above 20 inches are heavy and difficult to handle even for burly lumberjack types.

By contrast, that tiny woodstove you adore? It probably holds only 12-inch logs. If you’ve ever split cordwood, you know that 12-inch splits are the result of a lot of extra-hard work. The larger the firebox, the fewer times you’ll have to refuel it throughout the day, and you’ll be able to load it before turning in at night and wake up to a bed of coals in the morning.

So if you’re planning to use your woodstove as more than a secondary heat source, firebox size and BTU output are critical decision points.

Efficiency

Beginning in 1988 in the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency began requiring every woodstove sold in the U.S. to be EPA certified, to meet strict particulate emissions standards. More recently, the U.S. government has begun offering tax rebates as incentives for purchasing and installing stoves that meet a 75 percent efficiency standard. Cleaner burning, highly efficient woodstoves make sense from both an environmental and economic standpoint.

They more completely combust the raw material, which lowers emissions while delivering more heat per unit of wood to your home. All of this results in lower wood costs, less handling and less ash removal. The higher the efficiency, the less fuel you’ll consume and the lower your emissions will be.

Buyer beware: Stoves with an extremely low price probably aren’t EPA certified. There’s a loophole that permits highly inefficient stoves to be sold in the U.S. if they’re classed as fireplaces. Not only do these stoves consume large quantities of wood because they’re so leaky, but they burn the wood very inefficiently, with high particle emissions.

Catalytic versus Noncatalytic

There are two fundamentally different types of combustion systems that woodstoves utilize: catalytic and noncatalytic.

Catalytic stoves contain a honeycomb-like internal element that the smoke passes through; it effectively lowers the temperature at which the smoke is able to fully combust (enough to meet the EPA standard). Once the stove is up to temperature, the catalytic element allows the airflow to the stove to be greatly reduced, because the smoke can still completely burn at this lower temperature. This means these stoves achieve longer burn times and consume less fuel with lower emissions. One drawback to a catalytic stove is that the catalytic element must be replaced at a regular interval, which ranges from two to five years, depending on use and fuel burned. There’s also a learning curve to the proper operation of a catalytic stove.

Noncatalytic stoves have an insulated firebox, an internal geometry that’s designed to burn the products of combustion more completely, and a series of ports that inject preheated combustion air into the firebox. Many of the modern European stoves are noncatalytic. These stoves are simple to operate, look great and require little maintenance. They do consume more fuel than their catalytic counterparts and have slightly higher particulate emissions.

Interior Flue

Visible both inside and outside, above the roof, the flue (or stovepipe) deserves some consideration. There are two basic types of flue: single walled and double walled.

Single-walled flues require a greater clearance to combustible construction, as they transfer a large amount of heat to the surrounding space. While that sounds great for room heating, it has definite trade-offs. When flue gases get too cold, the by-products of combustion condense on the inside wall of the flue. Over time this build-up, called creosote, can be the fuel of chimney fires. It’s dangerous stuff and the reason you’ll want to do a yearly chimney sweep.

A double-walled insulated flue is basically a flue within a flue, with a noncombustible insulation sandwiched between. The added layer of insulation results in a larger pipe diameter, but it also reduces the required clearance to combustibles, because it doesn’t radiate the heat of the flue gases. This aids in the draft of the flue, and the higher temperatures mean creosote is much less likely to form or become a problem.

Where a flue penetrates a floor or ceiling, you’re actually required to use a double-walled flue. The transition is usually a larger box or cylinder that accepts the flue from below. This shields it from the framing and insulation and offers a tidy transition point to the insulated flue.

When selecting your stove color, be sure you can find a matching flue color. Some steel stoves are offered in a light gray, but you’ll find it difficult to locate a flue that matches. High-temperature paints matched to your stove color are an option in circumstances where the stove manufacturer doesn’t offer a matching flue.

Exterior Flue

When the flue reaches the exterior of your home, there are additional considerations; local codes, of course, being paramount. A general rule of thumb is that a flue must extend at least 3 feet above any roof surface. On sloping roofs the top of the flue must usually be 2 feet above any roof surface within 10 horizontal feet.

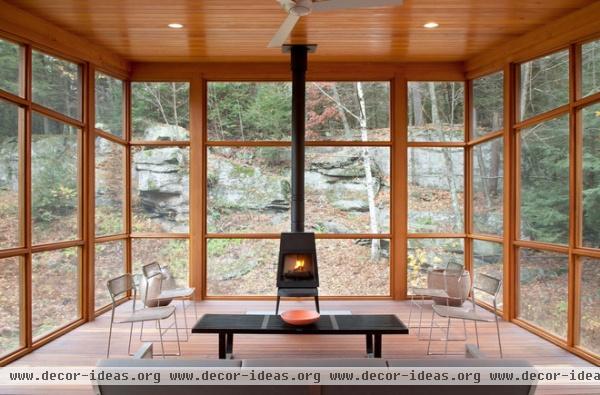

When planning the location of your woodstove on the interior, note the exit point and the roof lines above. A flue exiting on the low end of a pitched roof will mean a taller chimney and potentially guyed supports. The architect of the home shown here considered this vertical element as part of the overall building composition.

A bare metal flue isn’t the only option; if your preference is to conceal it, your options are virtually endless. Simple and direct are generally the most economical qualities, and I personally find flues as vertical elements to be beautiful.

The top of the pipe will need a rain cap, while some cities require a spark arrestor along with the usual cap flashing components to ensure that the elements don’t find their way inside.

Hearth and Wall Protection

All woodstove manufacturers offer an installation guide that lists required clearances to nearby combustible surfaces. The closer you choose to place the stove to the wall, the more protection you’ll likely have to provide.

Some manufacturers offer zero-clearance models that reduce the clearances to a bare minimum. Unlike with fireplaces, the hearth requirements surrounding woodstoves are less stringent. Consult your local codes and the manufacturer’s installation instructions for sizing, but as a guideline, typically a noncombustible finished surface placed on top of the subfloor will suffice. This means retrofits are entirely possible and makes planning for stone, concrete or tiled hearth areas during the initial stages of design dead simple.

Wood Storage

A nice feature especially for casual use is included wood storage. Integrated storage bins beneath woodstoves are usually too small to be practical. Planning for inside wood storage is a good idea, and keeping it self-contained and lined with durable surfaces will limit debris scatter.

This is probably a good time to discuss your relationship with wood. If you’re contemplating a woodstove as your primary heat source, you’ll have an intimate relationship with wood and the species that yields the highest heat output per log. It’s a lot of work. It’s said that heating with wood warms the body twice.

Retreating to a more casual relationship, using a woodstove as backup or secondary heat retains the rewards of having a shimmering fire on a cold night without the day-in, day-out hefting of logs and removal of ash.

Ash Pan

The most visible by-product of wood burning is ash. By purchasing a high-efficiency stove, you’ll be rewarded with relatively little ash left behind, as combustion is so complete. Frequency of use determines how often one has to remove ash.

If you use your woodstove as a primary heating source, it will mean daily ash removal, while more casual use will mean less frequent removal. Having an ash pan beneath the stove makes the removal process easier and less messy, so an ash pan can be a convenient accessory.

At the bottom of the firebox is typically a grate that is opened mechanically from the front of the stove. When you open the grate, the ash is directed into the pan, which can be slid out like a drawer and disposed of. When people reference dusty homes with respect to woodstoves, they’re probably referring to ash dust. An ash pan will reduce the amount of fine particles that make their way into your home, as the drawer will keep the ash contained when you’re removing it. Personally, I find these trays to be more hassle than they’re worth for larger volumes of ash, but they are no doubt less messy.

Room Layout

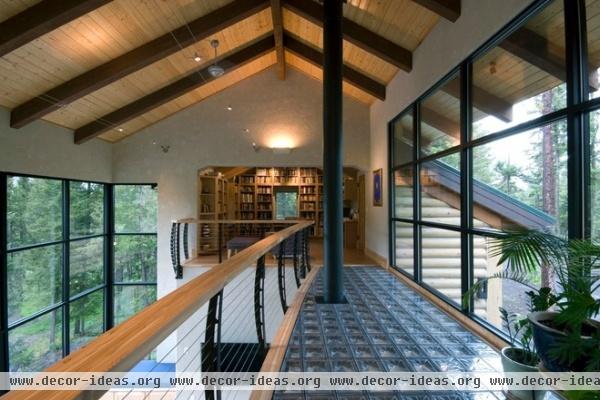

In an open-plan concept, a woodstove is an obvious choice. Without walls to impede the transfer of heat, the space will quickly heat up. Radiant heat from the fire warms the occupants as well as the air. Having some means of recirculating air from the upper area of a double-height space such as the one shown here will help limit heat stratification.

Aesthetics

This stove with an integral bench, designed by Antonio Citterio and manufactured by the Danish company Rais, is a focal point for the entire room. It’s but one of many outstanding design options available today, ones that challenge traditional notions of what a woodstove must look like.

I particularly like this stove as a freestanding object in the center of this space. It effectively subdivides a relatively large volume while offering even heat to the entire footprint. Obviously, in a home with children, this wouldn’t be an ideal configuration, but here it’s integrated with the architecture in a thoughtful way.

Cost

Assume that most of these stoves cost $1,500 to $5,000. Noncatalytic steel stoves fall on the lower end of the spectrum, and stoves with lower efficiencies will typically be the least expensive, at least up front.

Always consider the cost of operation as well. A less efficient stove will require more firewood, more stacking space and more of your time moving wood — costs and efforts that can quickly add up. For those choosing to supplement their heating system and reap the benefits of a fireplace without the inherent inefficiencies, a noncatalytic steel stove is a minimal investment with a quick return.

Maintenance

It goes without saying that heating with wood requires extra effort in the form of upkeep and tending. Heating with wood is a commitment that some will enjoy and others will find a chore.

Maintenance tasks include a yearly chimney sweep and a check of the stove for air leaks. During the heating season, the ash in the firebox needs to be cleaned out as it builds up, perhaps as often as daily, and sweeping up around the hearth and wood storage areas is an ever-present chore. Acquiring, stacking and moving wood will also become a part of your life. I personally embrace these as part of my choice to live in a cold climate, and I feel like the added effort is good for both myself and the environment — but it’s certainly not for everyone.

More: 8 Reasons to Nix Your Fireplace (Yes, for Real)