Design Workshop: Kinetic Architecture

Kinetic architecture, which moves or changes to adapt to seasonal, functional or daylight requirements — or just for the heck of it — has roots dating back to medieval times. A castle’s drawbridge served as a multifunctional kinetic wall, door and footbridge. The futurists and constructivists of the Russian art movement of the early 20th century explored kinetics by infusing their proposals with notions of highly mechanized, sleek, modern, industrial construction.

Today architects are afforded the freedom to explore kinetics even further because of advances in materials coupled with interesting uses of both old and new technologies. Planted living walls, windows that change aperture based on the amount of light they receive and single doors the size of an aircraft are just a few examples.

But while these differ in their execution, they share in the truly stunning spatial effects they create. And it’s easy to fawn over the bespoke nature of some of these constructions. The ones that personally resonate with me are those that use off-the-shelf industrial components to achieve the sublime. Let’s take a look at some modern-day kinetic architecture.

Folding Walls

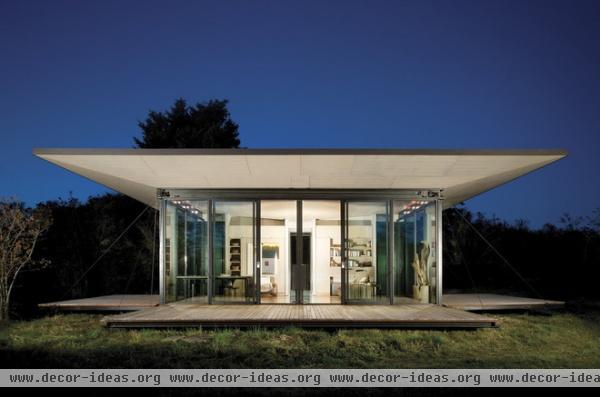

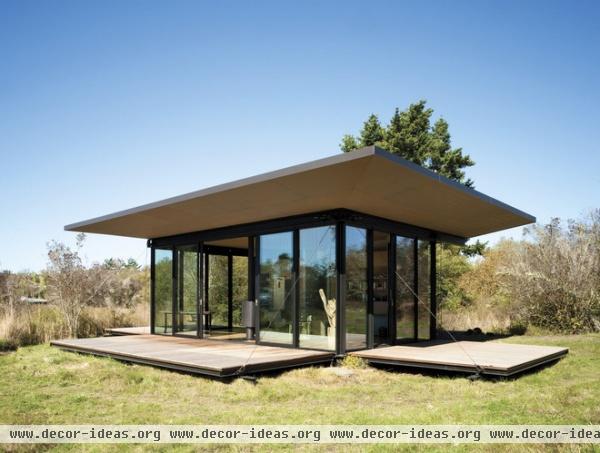

This writer’s cabin on an island off the coast of Washington state, designed by Tom Kundig, is a lesson in the power of kinetic skins. All three deck surfaces hinge along the building’s edge. Oscillating between glass box and shipping container, the studio offers vastly different work environments, from the cellular and protected to the exposed and vulnerable. In the lowered position, the walls act as exterior decks that gesture to the surrounding environment.

Here, with walls raised, the cabin becomes an introverted fortress. The support structure for the decks acts as the only exterior ornamentation. It’s barn-like and austere in this configuration; the only hints of the mutable shell are the inlaid deck supports on the adjacent ground. This tough exterior husk ensures that the outpost is secure when the owners are away.

Simple physical mechanics allow this configuration to transform. Employing a series of cables and hydraulic winches, three of the cabin’s four walls lower to become decks. The large south-facing deck can be operated independently of the smaller flanking decks, allowing for more variety. Raising the two side walls leaves the interior with a single glazed wall, creating a focused view to the landscape.

At 10 feet in height, the pivoting walls are substantial, but they make for suitably proportioned decks and serve to mark this structure’s place in a vast surrounding landscape. The kinetic walls allow a 500-square-foot interior to feel like 5,000 square feet when open, and 50 square feet when closed, a feat that’s difficult to achieve any other way.

When to use: Sparingly. This type of kinetic treatment is unique enough to warrant limited use. If used everywhere, aside from the prohibitive cost, it risks becoming gimmicky.

Pivoting Panels, Doors and Walls

These massive oversize panels match the scale of the view beyond. Eight feet wide and 16 feet tall, they are opened via a geared, motorized mechanism, similar to an overhead door operator. The mass and scale of these panels are interesting counterpoints to the openness of the glazing.

Remaining transparent and connected to the view, the pivoting panels have a certain visual weight. You sense this weight not only because the panels are connected to a motorized operator, so you intuitively understand how heavy they are, but also because you see the thickness of the wall upon opening. Very rarely does one have this sense with static wall elements. Pivoting doors this large make equally large statements about connecting indoors and out.

The pavilion-like space has an industrial character, which makes the mechanized pivoting door panels and their scale an appropriate fit. Machines have a natural order to their function. Much like a machine, the order in this spaces extends from the regularized structure, the cross bracing and the height of the window mullions, right down to the motor’s being positioned equidistant from the panel’s pivot point. A single motor controlling two panels simultaneously has an elegant simplicity to it.

When to use: Almost anywhere. Pivoting wall panels are versatile elements that can fit any architectural system, because they perform much like a door. Play with levels of transparency for heightened effects of concealment.

The Gizmo

The architect for the first project we looked at, Tom Kundig, refers to the mechanics controlling his kinetic constructions as gizmos. It’s an apt term for the idiosyncratic devices invented to control large moving parts in his designs. They function as more than just a means for operating large moving parts on a building’s facade; they become integral to the character of a space. Any moment in time when one interacts with a simple machine, especially one that does something as unique as these do, is memorable. These devices become imprinted on us in very real ways.

This project was a renovation of a structure constructed during the Industrial Revolution, a time when the very nature of machines was being forged. This gizmo employs mechanical advantage by way of a series of gears that use a small amount of force to lift up this large window. Kinetic walls blur the distinction between building components. Walls become roof planes; windows become sunshades. This ambiguity punctuates the surprise

one feels when a window wall rotates to become a roof.

With the window in the fully closed position, the actuator mechanism is a sculptural element in its own right; the mechanism and its inner workings are laid bare. Note the simple adornment of arcs in the support structure that correlate with the arc of the pivot point.

When to use: In highly specialized applications. Budget can’t be a factor; these mechanisms are expensive to engineer, fabricate and install.

Aircraft Hangar Doors

This is a truly unique iteration of the kinetic facade that takes a more off-the-shelf approach. Aircraft hangar doors have unusual requirements: large, unobstructed spans without interior overhead door tracks. Because these wall-size doors fold in on themselves and are self-supporting, they make it possible to open entire two-story walls to the outdoors with the push of a button.

Drawn from the idea of a classic orangery, a conservatory used to grow citrus trees in winter, this two-story addition to an 1880s Italianate villa stands in stark contrast to the building’s historic origins. An industrial interior and a rotating fireplace complement the high-tech aircraft door.

Completely dissolving the exterior wall when opened, the aircraft door leaves only uninterrupted space. Reinforcing connections between inside and outside lies at the heart of the use of kinetic facades in architecture.

A kinetic facade was used on this project as a solution to a design problem. The owners desired an exterior deck on the upper level adjacent to the kitchen and great room, but space constraints and setbacks allowed only for a very narrow deck extension. The architect opted to absorb what little space could be apportioned for an exterior deck to the interior, and in its place substituted a singular, massive, glazed aircraft door. The result: When the window is open, there’s a near seamless connection to the tree canopy and a larger indoor-outdoor “deck” than would have been possible otherwise. When the window is closed, this connection is maintained but an additional year-round, finished living space is provided.

Here we’re viewing from the lower level with the aircraft door open above; the architects introduced a movable bed for outdoor sleeping, and an open garage door links a children’s playspace with the exterior. Transforming the feeling of each of these spaces through the use of movable elements brought a wonderful variety and richness to this project.

When to use: For seamless connections between inside and out.

Movable Screens

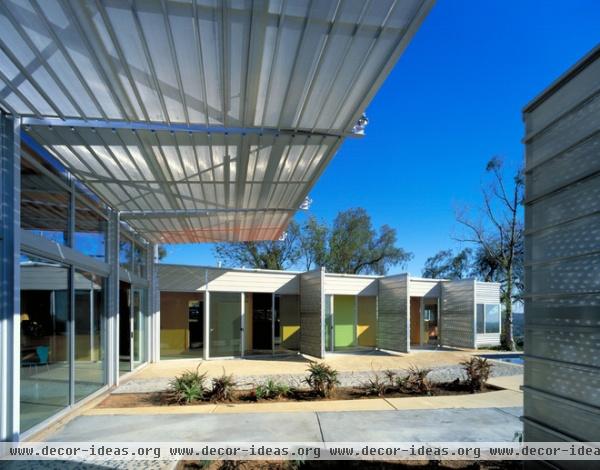

The design concept for this California home was inspired by the need to protect it from fire, which destroyed its predecessor. Using a series of layered fire-resistant skins on the exterior, the architects created a protective shell that has lightness despite its apparent solidity.

The overhead screens are large by residential standards, measuring 10 by 24 feet, but they’re easily controlled by small motors that permit their movement along cantilevered roof beams. Shown here near the midtravel point, these screens can be positioned to create a variety of effects. Their perforations scatter the desert light, removing the harshness in the summer and reflecting the lower angled sun inward in the winter.

In the closed position, the perforated aluminum screens act as a secure skin that would stop flying embers from hitting the home. This is a remarkable contrast to the openness the screens conceal.

The flanking bedroom wings have their own kinetic skins: bifolding perforated aluminum panels. These panels not only alter the shape of the simple rectilinear structure, but they modulate the sunlight entering the rooms. They provide shade for the exterior space and can be closed when the bedrooms are unoccupied. And, while they appear as solid elements, their perforations allow some light through as well as cooling breezes.

When to use: Of all the applications discussed, this solution can be adapted to the widest variety of projects, because of its applied nature. You can apply it to sunshades, light shelves, security devices, privacy elements, freestanding sculptures and wind blocks. Unlike some of the other devices, these movable elements can be used simultaneously in different ways around a structure without feeling overdone. They’re also the most affordable of the bunch.