Roots of Style: Queen Anne Homes Present Regal Details

Victorian houses hold a special place in the hearts of house lovers across the United States. Tall, proud and intricately adorned facades provide a delightful dance of visuals. But interestingly, Victorian is not actually a style, nor is it an apt description.

Rather, Victorian design defines an era, and American creations are distinctly different than their English cousins. The term “Victorian” arose from the long 19th-century reign of Queen Victoria in Great Britain. Several styles developed in the U.S. during the last decades of her reign, the Queen Anne style being just one.

The term “Queen Anne” comes from the label that 19th-century English architects assigned to their work, but it had nothing to do with Queen Anne herself. Her reign oversaw the Renaissance in Great Britain. The physical root of Queen Anne architecture is medieval and relates to the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras that preceded the Renaissance.

Brick Queen Anne examples primarily populate Eastern and Midwestern cities in the United States. This Chicago house illustrates the marvelously complex layering of details that defines higher-style specimens.

The forward-facing parapet gable alludes to medieval Jacobean or Elizabethan details found in England. A hint of classicism divides the upper-floor window grouping with a very slender capital, column and base.

In contrast, the Victorian era departed from masonry structures as the fashion spread westward. Balloon framing, which is the way we still build most houses, developed in the mid-19th century. The combination of the industrial revolution, an exploding population, the rapidly spreading railroad system and plentiful American forests fueled an extravagant use of those resources. The preceding heavy timber construction restricted plan shapes and forms, but the new framing system allowed much more freely configured buildings.

Victorian Queen Anne houses are found throughout the U.S., but no tour of this style is complete without a trip to San Francisco. The late-19th-century gold rush and plentiful nearby forests provided extraordinary opportunities to build in an exuberant fashion.

This is another American style that has wide variations in detail and form. Later examples are more likely to contain classical elements, such as the Ionic entrance porch columns on this house. Notice the swag details in the frieze above the first floor, too. The rounded bay window can be found on many Queen Annes in San Francisco, and it’s an especially sumptuous form. An oriel window at the center of the main level creates a punctuating focal point in a complex assimilation of details.

Notice the varying shingle patterns in the gable face of this San Francisco house, which at first seems more restrained than the previous example. There are at least nine common shingle patterns to be found in the Queen Anne style. You can see different applications on the neighboring houses in this photo.

Here there are full first and second levels, with a gabled attic floor completing the scheme, similar to the previous two examples. An Ionic pilaster detail frames each window and trims the corners of the bays.

A rounded two-story bay dominates this home’s Queen Anne elevation. Notice the classically detailed entrance porch. This detail foreshadows the onset of the colonial revival style, among others, which ultimately replaced Queen Anne and other Victorian designs by 1910.

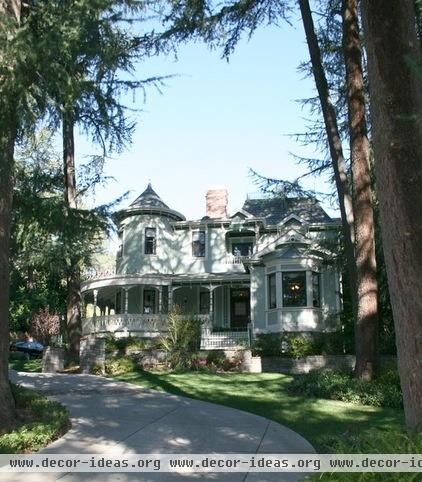

On larger parcels and in more suburban settings, Queen Annes often proudly host prominent tower elements, such as in this San Francisco example. Clear is the medieval form on houses of this type. The invention of wire nails and balloon framing enabled architects and builders to create free forms and irregularly shaped plans. The resulting complex elevations and layouts contribute to the enormous variations of this style.

Once again, comparing this house to the previous example, you can see the influence of classical elements.

Hipped, gabled and towered roof forms can all be used and often in combination. Masonry examples are rare and primarily reside in the U.S. Northeast. Half timbering, similar to Tudor, is also found, though it’s relatively rare. Most Queen Anne examples exhibit the elaborate spindlework or fretwork for which the style is well recognized. Classical elements combine with all of the above elements in later Victorian-era examples.

Wraparound porches are found on many less-urban examples, such as this Boston house. Notice the similarity to the shingle style, which coincided with Queen Anne architecture.

This Los Angeles–area Queen Anne revival blends into its setting. Its fretwork acts as the fractal, as do the branches of the trees. A gentle pastel green and cream color scheme hugs the surrounding landscape with ease. Part of the attraction of these houses is the organic feeling of their medieval forms.

While most of the examples here exhibit elaborate color schemes, this Queen Anne revival is dignified with an all-white body. Everything else is true to theme. The towered form on the right is nicely balanced with a rounded porch on the left lower level. Notice that the architect gave the roof asphalt shingles but provided a copper standing seam to underline the gable form.

This Queen Anne revival joyously incorporates two shapes of towers, spindlework, finials, wraparound porches, fretwork brackets and exposed gable trusses with a handsome contrasting color scheme.

Though the massing is complex, its roof is logically organized with a primary hip form, from which extend the gables, and the towers are at the corners. This organization isn’t obvious, but it cements the scheme.