Roots of Style: Classical Details Flourish in 21st-Century Architecture

Ancient Greece and Rome obviously provide the origins of classical architecture. What makes the subject relevant today is the high number of buildings and houses throughout Europe and America that have been designed with the aesthetics that developed in ancient times, and the interpretations that followed. While modern design theory relinquishes precedent for inspiration and formulation, there are still basic principles that great architecture relies upon: Symmetry, hierarchy, repetition and proportion are a few. The fact that classical architecture strictly follows these principles makes it an important architectural discipline to appreciate even today.

In the U.S. classical architecture has experienced three significant historical phases, in addition to its use today.

First, from about 1770 through 1830, the early classical revival era evolved with the cultural association of democratic Roman ideals as the U.S. was formed. Through the influence of the classical renaissance in Europe and architects like Thomas Jefferson, it gained followers.

Next came the closely related Greek revival phase, which lasted from around 1825 to 1860. A congruence of a desire to understand the roots of Roman classical architecture, which are of course Greek, and the Greek War of Independence propelled the affection for the prominently columned structures of this style.

Finally, classical architecture resurfaced with extraordinary popularity after the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where it was celebrated. William Ware's subsequent publication of The American Vignola, which dissected the conclusions about classical architecture by 16th-century Italian architect Giacoma Barozzi da Vignola, further advanced its proliferation and people's understanding of it. Other studies, such as that of Andrea Palladio, also propelled the interest in classical design, which sustained great momentum until about 1950.

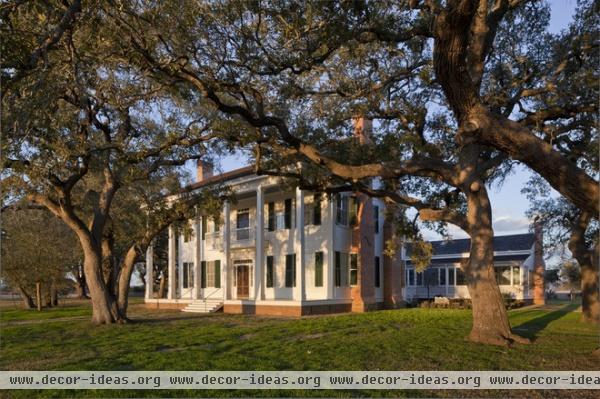

This 1847 Jackson, Mississippi, early classical revival house is somewhat simplified compared to others of the same era. However, the prominent centered pediment, or gable, rests atop two story-high columns topped with Ionic capitals. Its identity is certain.

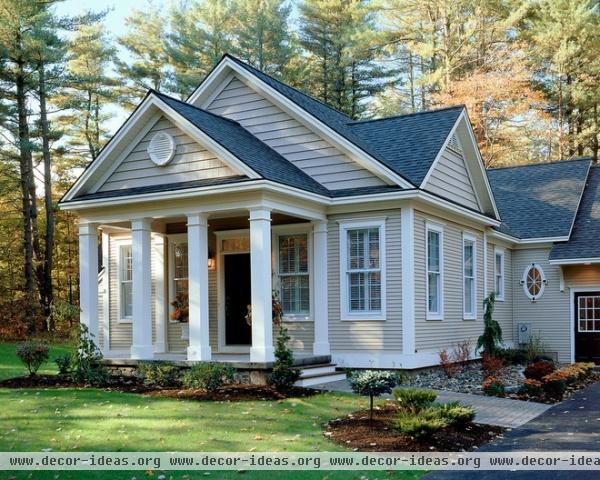

This contemporary Greek revival house makes the same robust statement as its ancestors. Of the five classical orders, its columns most closely resemble the Tuscan order. The flattened columns against the walls and at the corners of the building are called pilasters; they match the detail of the four round columns.

The band of detail above the columns to the lip of the eave line is called an entablature. This is divided in equal parts, from below to above, into the architrave, the frieze and the cornice. Details of the entablature vary from one order to the other, as well as from one architect to another, one carpenter to another and so on.

Doric, Ionic, Corinthian and Composite (Ionic and Corinthian combined) are the other four orders in classical architecture. Doric was the established system in Greece, while the Romans favored Corinthian.

Here an Ionic capital tops the column. The entablature is more correctly detailed in this example than in the previous one.

You can identify the architrave by the three flat bands just above the capital, topped by a band of molding. The next, much larger, flat band above that is the frieze. After that begins the cornice, with a more complex assimilation of shapes and details.

Notice the numerous individual scrolled elements in the cornice. These are called modillions; they lie in the same position as dentils would on other orders. Some orders have neither, some have one or the other, and some even have both modillions and dentils.

How is this all relevant to the abodes of today? Here you can see a simplified interpretation of classical architecture. There are four very simple square columns, and pilasters against the wall, each with a base and a capital. Two flat bands above the capitals imply an architrave and a frieze, while the trimmed fascia gives us the cornice. The gable face provides the basic pediment.

Typical of classical houses from the mid-1800s, a porch runs the full width of the primary elevation on this historic Texas house. This indelible theme defines more than plantation houses that were built in the U.S. South during that period. Banks, university buildings, hotels and scores of government buildings across the U.S., especially those built during the neoclassical period, have classically detailed colonnades with an imposing presence.

See more of this house

Look closely at the details on this South Carolina house. It has the same type of full-width porch. Though the columns are square, they still have an impression of a base and a capital. A minimally detailed entablature defines the eave and fascia.

And especially delightful are the pediment-adorned dormers. Though minimally scaled, their correct proportions make them especially handsome. Notice the detail above the windows under the porch. They are each capped with their own entablature. Finally, pilasters frame the entrance door and sidelights, and the group is also capped with its own entablature.

Very simplified details trim this newer Charleston, South Carolina, house, but the colonnaded front porch still makes the direct connection to the classical revival architecture of the past. Notice the slight asymmetry achieved with a composition of five columns, as opposed to the more common arrangement of four or six. The entrance door stays on axis to its corresponding columns but is off center to the whole elevation.

This new house has a traditional full-width porch. But the columns are supported with stone pedestals similar to those found in Craftsman houses. This view stays true to the symmetrical theme, while the pediment, or gable portion of the roof, gets set behind the porch roof.

What will we do with this classical inheritance in the future?

The elements of classical architecture are all around us. The details found in ancient classical ruins are so extensively ingrained into decorative arts, furnishings and all types of architecture that they will likely remain a significant influence even in a modern world.

It is true that modern design theory wishes to stand on its own merit, and it should. But does that mean that we cannot understand and appreciate what we have inherited from past cultures? Perhaps, as if by metaphor, a balance is possible.