6 Trees You'll Fall For

The leaves are changing, the nights are crisp. In much of the world, gardeners are laying down their tools, cleaning up their gardens and perhaps breathing a sigh of relief that another gardening season has come and gone.

But the planting season isn’t over. Fall — particularly until late October in colder areas of the country and until November in the South — is the preferred time to plant many species of trees. Planting conditions are near perfect: The soil is warm, the sun isn’t too hot and there’s usually more rain. The weather that makes people say, “Fall is my favorite time of year,” is ideal for many newly planted trees, too.

Different types of trees prefer different living conditions. Not every tree should be planted in fall, of course. The reason is in the roots: Trees with larger, thicker roots that reach deeper into the soil, such as magnolias and oaks, are better off planted in spring. Trees best planted in fall, such as crabapples, maples, elms and honeylocusts, have fibrous root systems shallow enough to readily reach water and nutrients. This allows them to settle in and put out new root growth before the weather turns frigid.

One of the best trees for small gardens, crabapples (Malus spp.) top out at a manageable 20 feet. They flower gloriously in the spring in shades of light pink, dark pink or white. Fruits follow, and although they must be cooked for humans to find them palatable, birds depend on them to get through the winter. Hardy to zones 5 (to -20°F) to 8 (15°F), crabapples need full sun and well-drained soil.

At the garden center, look for trees that are in containers or that are balled and burlapped. These can be planted in fall. Dormant (bareroot) plants must be planted in spring.

When buying a tree, always check to be sure it's healthy: no dead branches, splits or damage to the trunk. A damaged trunk interrupts the flow of water up and sugars down the tree. A tree may recover, but a damaged trunk can ultimately kill a tree.

Some Great Trees for Fall Planting

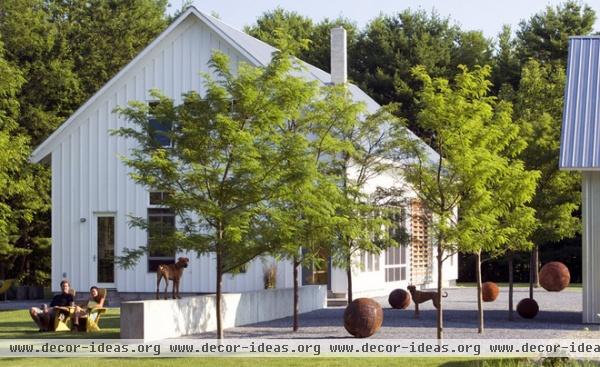

Native to North America, honeylocusts (Gleditsia triacanthos) have fern-like leaves that provide airy shade, so they are a good choice if you want shade but not too much. The species has fierce thorns and grows well over 80 feet tall, but cultivars are thornless and grow to about 40 feet. They need full sun and are hardy in zones 3 (-40°F) to 7 (0°F).

Green hawthorn (Crataegus viridis) is a lovely tree with three seasons of interest: white flowers in spring, red fall foliage, and in winter, red berries that birds adore. Hardiest in zones 5 (-20°F) to 7 (0°F), hawthorns stay under 40 feet. They require full sun and do best in soil that's not too rich or too moist. The cultivar 'Winter King,' shown here, is especially disease-resistant and drought-tolerant.

There are about 35 species of spruce (Picea spp.), cone-bearing evergreens, native to the world’s colder zones. Many are hardy up to a teeth-chattering zone 2 (-50°F), but some tolerate the warmth of zone 8 (10°F), meaning there’s a spruce for almost every garden. Their dense branch structure and sharp needles provide shelter and protection for birds. Many, like the native Colorado blue spruces (Picea pungens) here, grow 50 to 75 feet tall. Spruce trees need full sun and a neutral to slightly acid soil.

Perhaps the ultimate specimen tree, Japanese maples (Acer palmatum) come in an almost bewildering array of shapes, sizes and leaf colors. They are elegantly beautiful in every season, in leaf or bare-branched. Japanese maples are hardy in zones 6 (-10°F) to 8 (10°F) and need both sun and shade. Too much sun and their leaves can burn at the tips.

In the United States, our native elms (Ulmus americana) have been all but wiped out by Dutch elm disease. These huge shade trees, reaching 80 feet and taller, once lined streets across the country. Scientists are attempting to breed native elms with non-natives that are resistant to DED. Some of these non-natives, such as lacebark elm (Ulmus parvifolia), which grows to about 50 feet, are lovely in their own right. Hardy in zones 5 (-20°F) to 8 (10°F), elms require full sun and lots of room to grow.

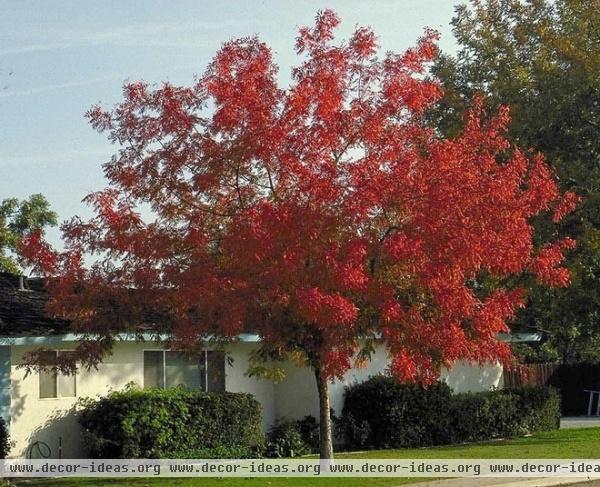

A great tree for the warm zones 7 (0°F) to 9 (20°F), Chinese pistachio (Pistacia chinensis) does not, alas, produce the edible pistachio nuts we all covet. That takes nothing away from this versatile tree. Pollinators visit the flowers, it has brilliant fall foliage, and it produces blue fruits in winter. Maturing at about 35 feet, it requires full sun and well-drained soil, and is drought-tolerant once established. Don't be put off by its gawky and unpromising appearance when young; this tree grows up to be a showstopper.

Remember to site your tree according to its needs for sun or shade, soil pH and moisture requirements. And always check with your local utilities before you start digging to identify underground power, gas and cable lines.

Whether spring or fall, trees are planted the same way: Dig a hole twice as wide as it is deep, set the tree in the hole to the depth of the root flare, backfill with soil, water deeply and mulch.

Don’t fertilize; that encourages top growth that may be killed by frost. You want the tree to concentrate on root growth.

The old advice was to stake every newly planted tree; the new thinking is that the tree grows stronger and straighter without being staked. However, staking is a good idea if your site is especially windy or the tree is in danger of being clipped by a lawn mower. The stakes will keep the blades of the mower from getting too close.

And most important: Trees planted in fall should be watered occasionally throughout the winter, when there's no snow and the ground is slightly thawed. Water trees from the trunk out to the drip line (the distance the branches extend.)

Need another reason to plant a tree (or trees) in autumn? Garden centers are slashing prices on leftover plants. You might discover a bargain that rewards you for years to come.

More Houzz guides to fall gardening