Houzz Tour: A Salvaged Airplane Becomes a Soaring Hillside Home

One of the many aircraft boneyards — where airplanes are taken when they're retired from service — can be found in the Mojave Desert, where natural corrosion is reduced by the dry air. It is here where Francie Rehwald and her architect, David Hertz, traveled in 2005 to select a commercial 747 that would be transformed into a house in the hills above Malibu, California.

It was a relatively quick jump for Hertz from the initial sketches envisioning a curved ceiling to the reuse of airplane wings, but the house's realization was a much longer process. Not only did the airplane have to be disassembled and shipped via trucks (necessitating closing parts of highways) and helicopters (to bring the 747 pieces those last few miles), but a number of government agencies had to sign off on the creative reuse of the Pan Am aircraft.

So five years after buying the airplane parts for $50,000, Rehwald can finally call the 747 Wing House home. This tour takes a look at the house from the outside to the inside, revealing how it is a unique bit of recycling in the landscape but also how it commands some amazing views of the same.

Houzz at a Glance

Who lives here: Francie Rehwald

Location: Malibu, California

Size: 4,700 square feet

Hertz says the idea of using a 747 came from the fact that each wing covers about 2,500 square feet. In early studies he positioned various wings on a model of the site, with the intent of maximizing views and reducing the structure needed to support the wings.

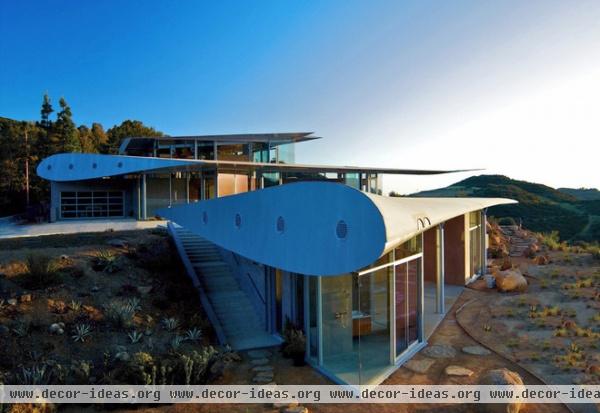

As realized, the wings step down the terrain to allow views from one level over the lower level. This also has the effect of giving visibility to the wings and creating in-between spaces, such as the one pictured here, where Rehwald can feel like she's in flight.

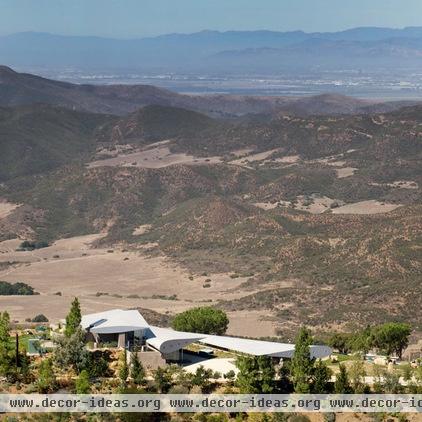

From above the house looks like a scattering of plane parts, most prominently the wings. For this and other reasons, the project had to be registered with the FAA, so pilots do not mistake it as a downed aircraft.

Hertz used as much of the plane they purchased as possible — not just the wings that make up the roof of the main residence and master bedroom. A number of related structures (art studio, guesthouse, animal barn and meditation pavilion) are constructed from other parts of the aircraft.

This view clearly illustrates the way the house steps down the hillside so views can be had from each level. The teardrop section at the end of each roof (where it would have connected to the plane's body) is a great touch, accentuating the thickness of the wings and how they taper to the ends.

This is my favorite view of the house, where the use of the wings is most dramatic. They have an alien presence in the landscape, as if they are resting in Malibu, just as they rested in the Mojave.

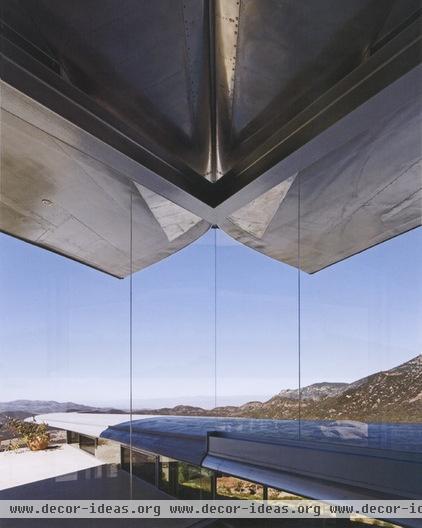

This photo, taken at dusk, accentuates the transparent nature of walls that serve to capture the view. Concrete walls built into the hillside serve as the primary structure for the roof (wings), thereby enabling the exterior to have so much glass.

A slightly closer view reveals that the undersides of the wings are very important. Their smooth, reflective surfaces parallel the ground, such that these planes (no pun intended) and the distant horizon shape one's experience of the house.

From inside it's clear how Hertz used the wings as a means of capturing the amazing view. It's easy to focus on the wings as objects, but their long span and smooth surfaces allow their presence to recede in favor of seeing the earth, sky and horizon.

But of course the fact the house is partially built from a 747 is undeniable. In areas like this, even as the wing form subsides in the twilight, it reasserts itself through the lights that illuminate the terrace.

Much of the interior consists of concrete walls, columns and ceilings where the house is built into the hillside. These surfaces are at the service of the glass and views opposite, but they are the logical places for bathrooms, mechanical space and the like, as well as backdrops for art.

Visible in this photo and the previous one are the clerestory windows that were formed by terracing down the hillside and by propping the wings upon the concrete walls and columns. These high windows bring in additional sunlight from the south, important since most of the full-height glass walls face north.

The master bedroom is one place where the clerestories of the level below actually make up part of exterior wall. This means that one can see down into (and through) the living area below, but also that the wing of the lower level reaches into Rehwald's bedroom. From here she can step out onto her terrace and walk up onto the wing of the floor below. This is something that — as she mentioned in a recent TV interview — pilots were never able to do during their work.

Hertz designed the glass walls to be predominantly free of framing (except where they are operable, as in the previous photo). In the master bedroom, that means the corner disappears to embrace a panoramic view of the near and distant hills.

This last view of the house reinforces the way the three solid surfaces — airplane wing, floor and concrete wall — work together to open up the house toward the prized views. But I'm drawn to the small windows mounted on and in the concrete wall. As Hertz put it, "Like the Native American Indians used every part of the buffalo, it made sense to use as many of the [airplane's] components as possible." The 747 Wing House is full of large and small reminders that reuse is limited only to the creativity of designers and the openness of clients.