Sunlight Used Right: Modern Home Designs That Harness Solar Power

http://decor-ideas.org 11/09/2013 23:50 Decor Ideas

The changing colors of trees in fall signals that soon we'll need to turn on the heat. It makes me realize how valuable the sun can be for heating our houses, saving energy and reducing bills — the flip side of designing a house for living without air conditioning. Designs for passive solar heating work on two principles: maximizing the amount of sunlight that hits a house's interiors in the cold months and storing that heat so it is released inside after the sun goes down. This ideabook looks at a few houses to see ways to design for the benefit of each.

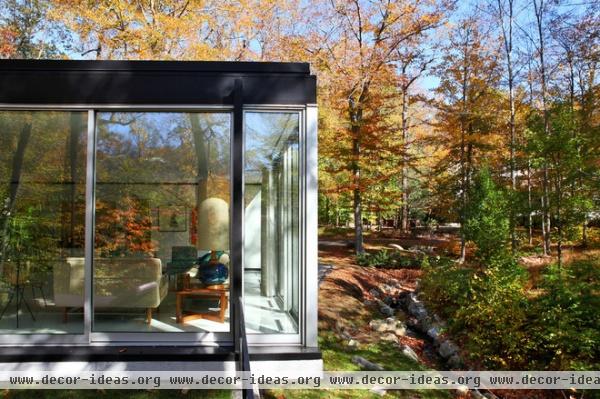

What this ideabook does not promote is fully glazing the exterior walls of a building, no matter how much beauty one may find in such architecture or the views it enables. Depending on window shades and other devices, glass boxes overheat during the day from too much direct sunlight and lose heat at night, due to the large expanses of glass and their low R-values (insulating values) compared to solid walls.

Rather, we'll move from big to small, from the site and house orientation to means of selectively admitting sunlight and trapping that heat.

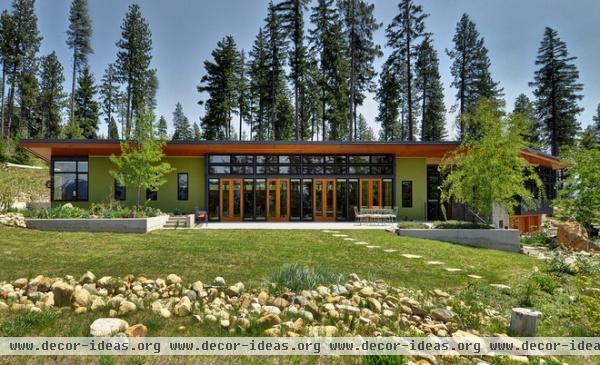

To gain the oh-so-valuable rays of the sun, the ideal plan for a house is a linear one with living spaces oriented to the south (in the northern hemisphere; to the north in the southern hemisphere). It's then good practice to place deciduous trees on the same side, so the sun is filtered in the hot summer months, but with the leaves off the trees in colder months the sun can penetrate to the house's interior.

This house near Seattle, designed by Mohler + Ghillino Architects, opens up toward the sun, but it also takes advantage of fir trees to the north to block cold winds in the winter.

A peek at the north side of the same house also reveals how it is partially bermed into the ground, a good tactic for taking advantage of the relatively constant temperatures of the earth. Minimal openings on the north also mean that internal temperatures — increased by the sun in colder months — are well contained, not lost to the exterior through windows, doors and their joints.

A peek inside the house shows the relationship between the wall of glass and glass doors we saw two photos ago. Sunlight enters the open-plan kitchen-dining-living area. A couple of things worth noting are the roof overhang, barely visible here outside the clerestory windows but more noticeable in the previous photo; the overhang cuts down on heat gain that happens in the summer, while allowing the sun in during the winter. Also, the concrete floors act as a thermal mass that absorbs the heat of the sun, releasing it at night after the sun goes down.

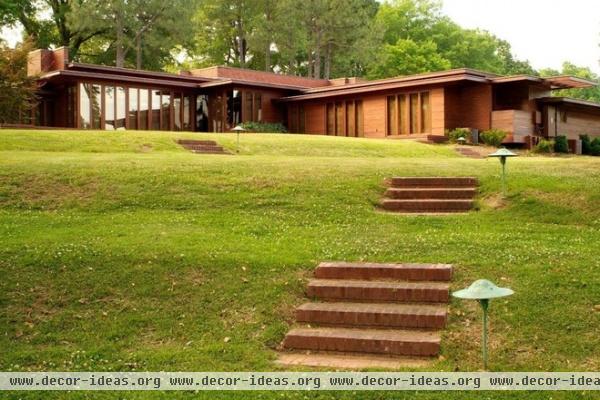

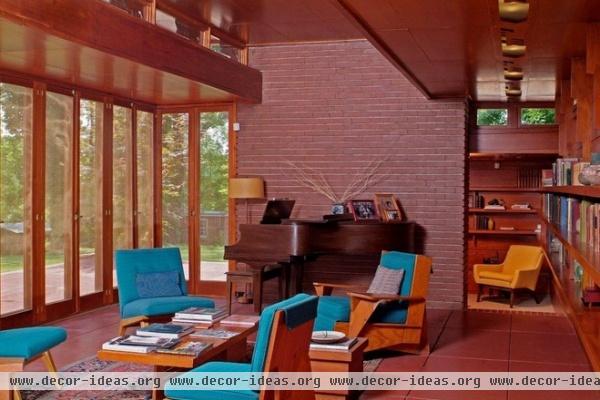

One of the architects who strongly embraced passive solar heating (as well as sensible heating through radiant floors, but that's another story) is Frank Lloyd Wright, especially with the Usonian houses he started in the mid-1930s. Shown here is the restored Rosenbaum House in Alabama, specifically the back of the house, whose large glass walls face south and west.

As mentioned in an ideabook on Anthony Denzer's book The Solar House, architects have been developing ways of harnessing the sun's energy to heat houses without the need for solar panels and other mechanical devices. Wright is but one early proponent of an approach that continues to this day.

Wright's Usonian houses were opened up toward the sun and almost completely closed off on the cold side. The small windows of the latter, combined with the full-height glass doors and screens of the former, allowed for cooling breezes in warm months.

But the glass doors and concrete floors worked together to embrace and absorb the sun during the winter. Having stayed in one of Wright's Usonian houses during a power outage both in the summer and winter, I can say firsthand that his houses respond remarkably well (given help from the occupants) to the heat and cold.

On approach to this residence in Michigan, one can see directly through double-height glass walls on both sides of the linear plan. It's safe to assume that this side faces north, given the small openings that surround the double-height space.

On the south side, the building opens up even more, for both views and sun. Note how the double-height space is set back from the adjacent walls, but the roof maintains its straight line. This allows for more summer shading in this area, while allowing plenty of low winter sun inside.

From inside we can see the way the house receives sunlight into the living room. We can also see some trees in front of the window that help cut down on summer sun but lose their leaves in the winter, therefore not blocking the sun's rays when needed for passive solar heating.

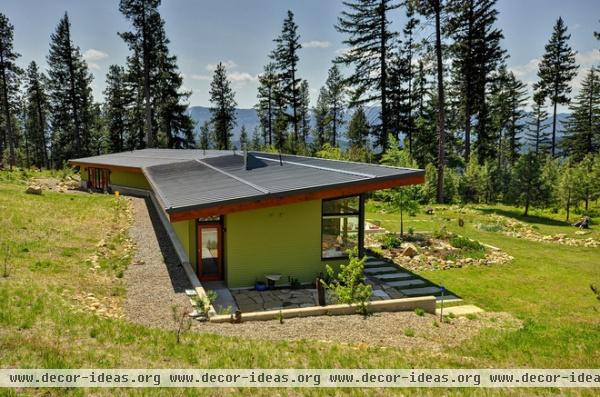

It is worth delving here into Passive Houses, which follow German Passivhaus principles, which are focused on superinsulated and supertight exterior walls to keep the cool or warm interior air inside. (Heat exchangers allow for fresh air without affecting the internal temperature, but that's not something I'll get into here.)

This house in Oregon, designed by Holst Architecture and built by Hammer & Hand, aims to meet Passive House standards. The view shown here is what one might expect with such a goal: predominantly solid walls with small openings. This follows from the assertion that even triple-insulated glass has a lower R-value than solid walls.

But Passive House principles are not absolute, so the design of the windows follows from the site and its myriad considerations: sun, wind, views, trees etc. In the case of this house in Oregon, larger windows facing south are used to bring in much-needed solar energy to the interior. The architect used a second-floor overhanging balcony (among other strategies) to provide some shade from the summer sun.

The triple-layer insulated windows and doors let in plenty of low sunlight in winter, generating lots of heat that is then trapped within the supertight envelope. Ideally, houses following Passive House (and stricter net-zero) guidelines absorb enough heat from the sun and other sources to eliminate the need for mechanical heating.

This last house, in Jackson, Wyoming, was designed by Chicago's Nagle Hartray Architecture and built by Teton Heritage Builders. The south-facing glass is expansive, but it is strategically fit into the timber frame to admit the sun inside but also shade the home in parts.

The glass allows the home's interiors to capture the stunning distant views while gaining some direct sunlight. Shades mounted above the sliding wall sections allow for shading in the summer months; important, given the lack of trees.

Elsewhere louvers are mounted in front of the glass to help shade the interior, while the two-story sections adjacent to the double-height living space also help to block the summer sun.

For more on strategically shading interiors so heat can be gained in the winter rather than the summer, see this ideabook on louvered sunshades.

More:

Life Without Air Conditioning

Look to the Sun for More of Your Lighting

Related Articles Recommended