On Show: The Ingenuity of Ancient Architecture

I was a magazine travel editor in a previous life, and one of my favorite places to visit was the Caribbean. It wasn't until a couple of years ago that I finally made a point of asking a local, "Why so many gabled roofs?" And I was told, "They help stabilize the structure during high winds from hurricanes and tropical storms." That might seem strange to many of us who live in new builds or in copycat house styles that we chose for no other reason than we liked the way they looked.

But several cultures continue to build homes more purposefully. The houses are built to take advantage of the power of the wind and sun, or to protect against a hostile environment. For example, the Moroccan dar home has a central courtyard that acts as an air shaft, the walls are built thick and the houses are low, to make the searing heat more bearable.

Some cultures need to get creative with local materials, because that's what they have to work with. But that doesn't mean what they build isn't pretty. In fact, some are quite stunning. It is what author Bernard Rudofsky calls "architecture without architects."

A current exhibit at the Vitra Design Museum in Weil Am Rhein, Germany, shows approximately 40 houses from around the world in film, photos and models, illustrating the diversity and ingenuity of what is created from mud, bamboo, straw, cow dung, macerated juices and palm stems.

The exhibit, Learning From Vernacular (through September 29, 2013), also shows new construction in modern cities that was inspired by these traditional techniques. The exhibit itself is housed in one such example, designed by architects Richard Buckminster Fuller and T.C. Howard.

The Buckminster Fuller trademark geodesic dome gained worldwide popularity during the postwar period and is based on a tent cupola. The dome shown here was built in 1975 and put in its current spot at the museum in 2000.

Now on to some examples of architecture built by communities of people, not one guy or gal.

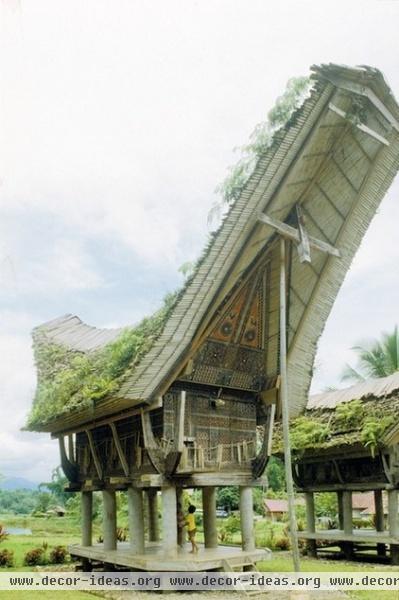

Batak dwelling. The Batak Toba tribe, which lives in Sumatra, Indonesia, once had a ritualistic society; the villages were composed of many of these boat-like houses, each serving a different function. This one rests on pillars of wood that were selected according to the sound they emit. The pillars were slightly elevated to protect them from the damp land, where mainly rice was cultivated.

The steeply pitched thatched saddle roof protected living areas; the eaves were intricately carved with ritualistic symbols; and the entrance was a trapdoor at the top of a stairway.

The space underneath served as a stable. Although many of these traditional homes are abandoned and in disrepair now, they did withstand earthquakes.

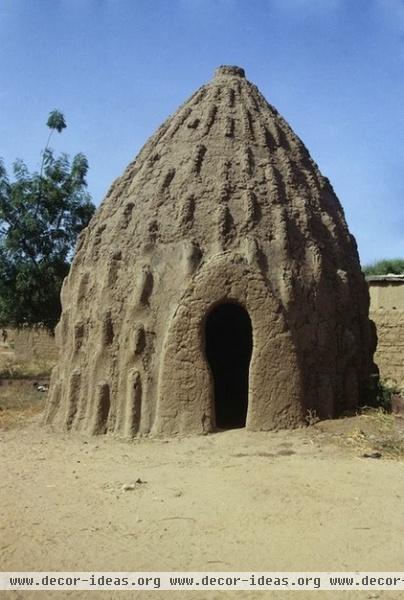

Shell house. Inspired by termite hills, from which they take their shape, the shell houses of the Mousgoum people of Cameroon in West Africa illustrate the possibilities of earth architecture. These beehive-like structures are made of a mixture of dirt, straw and vegetable glue, all of which are dried in the sun.

And talk about creative use of a tool: The vertical markings were created with forearms to reinforce the exterior of the shell, help water drain and act as a type of scaffolding.

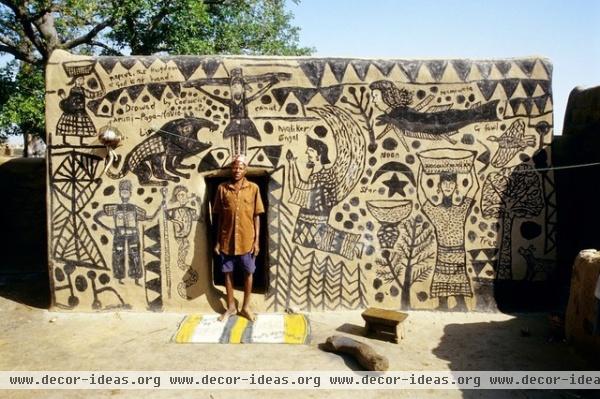

Traditional Kassena house. If only we could cover the facade of our houses in such an expressive, beautiful way. This is the work of the Kassena people of Burkina Faso in West Africa. The building itself is made from sun-dried clay, soil, gravel, maceration liquid and cow manure; the process is similar to that for making pottery. The exteriors, drawn with chalk and colored mud, tell a story through symbols. And since it rains for seven months of the year, the roofs are slightly sloped; it can also be hot during the day and cooler at night, so the entrances are low to the ground, and there are no windows.

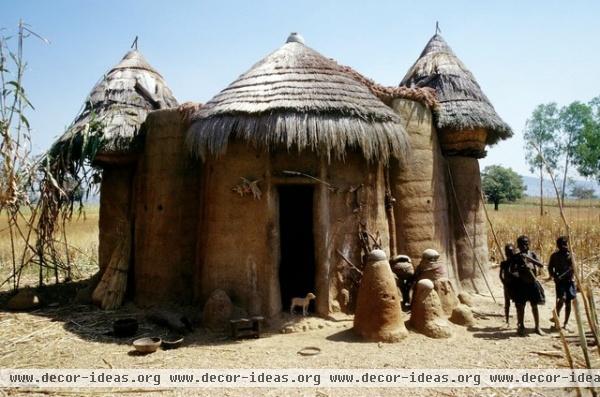

Tata. With only wood, hand-formed brick and straw used to build the tata, it seems fitting that the translation for "Tamberma" — the name of the builders, who live in Togo, West Africa — is "real architects of the earth," according to museum documents. The tatas look like mini fortresses.

Indeed, there was only one door in the tata, so the Tamberma could trap enemies. There were also no windows, as protection against the heat, and there usually five buildings within a tata, each with a different purpose (as you can see from the museum model). Dead ancestors and spirits occupied the first floor, while the family lived on the upper floor.

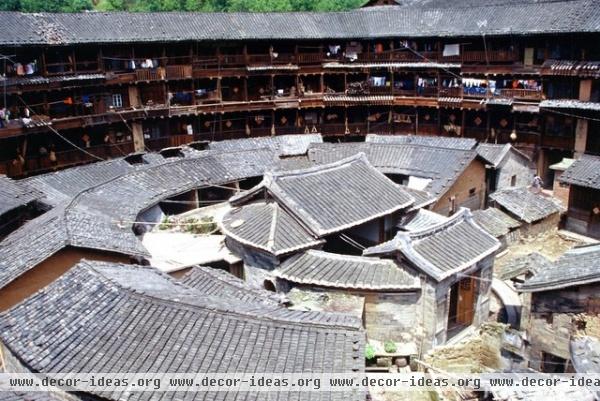

Hakka tulou. The circular hakka tulou mud dwellings in China's Fujian province reflect an egalitarian society with a feng shui sensibility: All families were allocated an identical amount of space, and each dwelling harmonizes with the land. Each of these little kingdoms, as the compounds were called, housed up to 800 people, who chose communal living as a means of defense against bandits. The round shape also protected villagers from the wind.

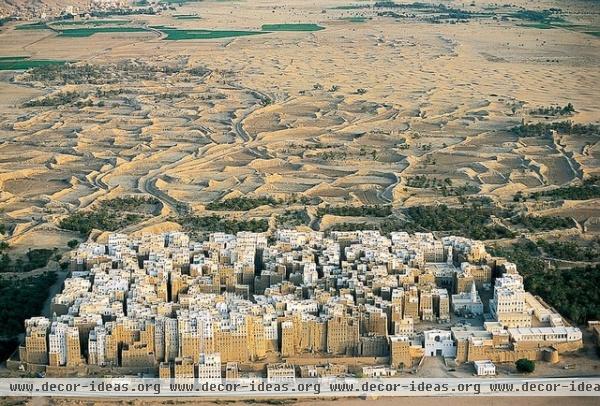

City of Shibam. Built in the 1500s, Shibam, Yemen, has been nicknamed "the Manhattan of the Desert" for the lessons it offers in vertical urban planning, only it's not built from steel but sun-dried mud brick. Floods in the surrounding land were used for irrigation; they also provided mud for building and rich soil for agriculture. A disastrous flood destroyed the first city, built around A.D. 300, but some older buildings remain.

Architecture Today

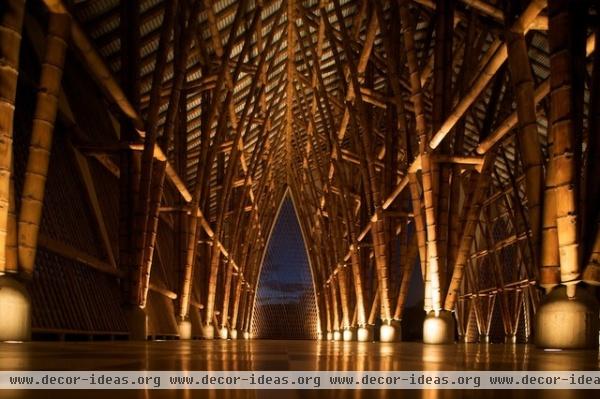

Today some architects are using nature's materials and traditional techniques. Take, for example, the Pereira Cathedral (shown) in Colombia. It resembles the Batak dwelling in Indonesia shown previously. And that isn't a coincidence.

"My architecture is tropical architecture," says Simón Vélez, who built the cathedral in 1999. "In a country where it rains a lot, you have to build roofs with large overhangs, like in Chinese or Indonesian architecture. Learning about Indonesian architecture was a radical development in my life — huge bamboo roofs built without any restraint or reserve." Vélez is widely considered to be a master of bamboo and considers timber grass to be better than steel. The world-renowned architect chooses it for its light footprint, low cost and earthquake resistance.

“I always thought that a roof or a room should not exceed a certain height," he says. "But in Indonesia, poor folk build roofs with their own hands that are 30 or 45 feet high! It’s a cultural statement: to create something momentous, a sort of exhibitionism without showing off.”

Architect Bijoy Jain of Studio Mumbai trained in the United States but was always determined to return to India to create a practice that used local building techniques and materials. Jain notes that the carpenters of the Palmyra House (shown here) were born of seven generations of craftsmen. Surveying the state of architecture, Jain says, “We have lost dignity, given up that position of doing things with a certain discipline.” He adds, “That’s probably why we are fascinated with the old, because of the intrinsic quality of what brought that about.”

For the Palmyra House, the structural framing was built of a local hardwood. The extensive louvres were hand crafted from the outer part of the palmyra trunk (a local palm species). The exterior is detailed with hand-worked copper flashing and standing-seam aluminum roofs; the interior surfaces are finished with teak and India Patent Stone, a refined pigmented plaster. Locally quarried black basalt was used to construct the stone plinths, aqueduct walls and pool plaza.

It's an interesting question: Does a village build a better house than one man or woman? What do you think?

More:

Back to the Future of the House

Vernacular Design: Architecture's Regional Voices