Architect's Toolbox: The Sketches That Spark a Home

With everything that goes into building a house today, it’s tough to imagine where everything starts. How exactly do you communicate your ideas to another person, and how does an architect interpret things like “indoor-outdoor flow, lots of natural light and a connection to the landscape”?

While architects use a variety of high-tech approaches to communicating conceptual designs to clients, including iPad mock-ups, computer-aided drawings (CAD) and 3-D models, the first versions of a design tend to begin with one of the most low-tech art forms around: the pen-and-paper sketch.

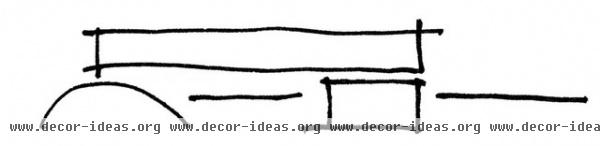

"That big idea, the whole project, has to be distilled into one little drawing. We call [them] ideagrams," says Vancouver architect Sean Pearson. "It’s an absolutely simplistic representation of the idea.”

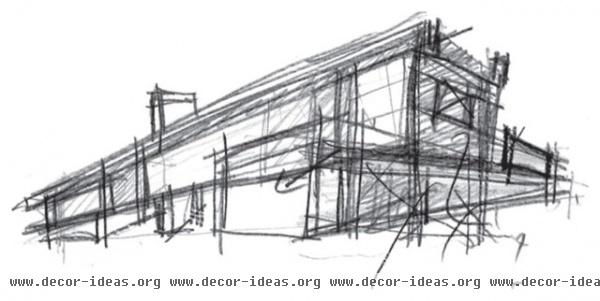

Architect Jim Castanes prefers drawing by hand in the early stages. "I have more control of scale," he says.

For a project on the beach in Seattle, shown here, he walked the property several times before inspiration struck. “All of a sudden, I thought, ‘I don’t want the house to be there and interrupt the movement of the natural beach, symbolically, metaphorically or physically.” He thought the house should float above the beach. The clients wanted something simple, and he couldn't think of anything simpler than a flat, sloping roof and a raised-platform design.

Castanes also pulled inspiration from things along the beach. Kids playing with beach balls and flying kites inspired him to incorporate colors into the exterior of the house. "Beach architecture here is usually all gray or all brown. I didn't want that," he says.

“You’re constantly talking to the client, and they’re telling you things," Castanes says. "You see the land, generate ideas. As an architect, you can wake up at 2 in the morning and think of details of how this fits and that fits. You don't get away from it. You’re constantly walking into a space and analyzing it — a nightclub, a bar — it’s everywhere."

People have to get a lot out of those sketches, so "you have to be focused," he says. "They have to be good enough to show to a client. Sketches are pretty intense. You’re under the gun, under a fee; you can’t screw around. You have to take into account the program, site, fee constraints, time — they’re superimportant.”

Pearson used only 11 lines to convey a concept to his clients on Gulf Island in Vancouver. He wanted to show how the design would consist of a rectangular main living space that appeared to float about the landscape, forming a bridge between a rocky outcrop (the arch) and the lower guest portion of the house (the square).

The 5,600-square-foot house mirrors the original concept drawing; it hovers above the rocky terrain and has glass walls that capture ocean views. "Drawings and models are tools to take abstract things in your mind and start to test them,” Pearson says. “You then simplify those and show them to the client. What people see from architects are the distilled, simplified versions of the design process."

Pearson's client was torn between wanting a traditional log cabin and wanting a modern design. Pearson tried combining these concepts by incorporating enormous wooden beams. Here he worked out how the beams would be configured to form the upper portion of the house.

Because all the materials would have to ship to the site via ferry, Pearson had to design the home around 108-foot-long beams, the longest allowed on a ferry.

Alaskan yellow cedar beams lend log cabin style to the final design. “The job of an architect is very complicated," Pearson says. "You have to be cost conscious; understand structure, materials, design; and combine all that into something you really can build. There’s contracts and legal structures around a project. Then you have to balance the criteria of what a client wants, the site, the regulations — you have to solve that puzzle."

Coming up with the initial sketch, Pearson says, can take a week to three weeks.

Architect Caleb Johnson sees sketches as a way to help sell his idea and let the client know what he or she is getting into — even if that client is his wife. Johnson used his artistic abilities to show his wife the design he intended to build for their new house in Portland, Maine.

"She has to agree with what I’m about to build,” he says. For this project he made a schematic drawing on the computer, then printed that out and used tracing paper to add in more detail. “It’s pure simplicity and getting down to the bare essentials," he says.

Architects: Please show us a favorite preliminary sketch!