Slow Design: Today's 'Wabi-Sabi' Helps Us Savor the Moment

I've been examining the parallels between modern Western design and wabi-sabi, the ancient Japanese philosophy of finding beauty in things that are imperfect, impermanent and aged. We saw how the philosophy paralleled the Shaker and Arts and Crafts movements, as well as midcentury modern design.

Today wabi-sabi manifests itself in the Slow Design movement, founded in 2006 by Carolyn F. Strauss and Alastair Fuad-Luke to slow down the metabolism of people, resources and flows. Strauss and Fuad-Luke’s Slow Design manifesto urges designers to “satisfy real needs rather than transient fashionable or market-driven needs” by creating moments to savor and enjoy with the human senses.

There's also a push to design spaces for thinking, reacting, dreaming and musing. In other words, the concept embraces designing for people first and commercialization second, and it aims to balance the local with the global, the social with the environmental — all in all, a transformation toward a less materialistic way of living. This basically mirrors the wabi-sabi approach to design. Here are the six principles of Slow Design.

1. Reveal. Uncover spaces and experiences in everyday life that are often missed or forgotten.

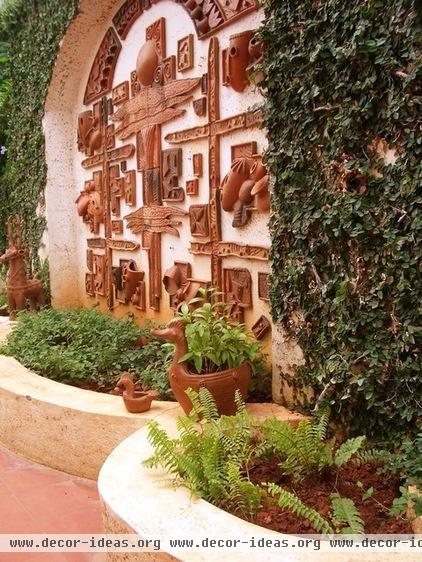

The manifesto urges people to "think beyond perceived functionality, physical attributes and lifespans to consider artifacts' real and potential 'expressions.'" This wall displaying Mexican artifacts is a good example. Working with undervalued materials is another.

2. Expand. Slow design considers the real and potential “expressions” of artifacts and environments beyond their perceived functionalities, physical attributes and life spans.

This principle asks designers to consider aspects beyond shape and aesthetics, paying attention to how we live and interact with spaces and objects. In their paper "Slow Design Principles," Strauss and Fuad-Luke cite Swedish designer Ramiz Maze’s contention that “design is not only about the spatial or physical form of objects, but the form of interactions that take place — and occupy time — in people’s relations with and through [them].”

These stairs, which provide a fun way for a child to learn how to count, show this principle in action. The design expands on more than just its material construction and arrangement.

3. Reflect. Induce contemplation and “reflective consumption.”

“Product designers are questioning not only ecological values, but also perceptual and emotional experiences that the unique materiality of products can deliver,” Strauss and Fuad-Luke state. They encourage designers to emphasize ephemeral beauty that reminds us that everything is transient and short-lived.

Strauss and Fuad-Luke cite Icelander Katrin Svana Eythórsdóttir's biodegradable chandelier, made from highly reflective glucose droplets; it slowly disappears within months, "inviting its owner(s) to savor every moment of its existence," they say.

Waterfalls, like this one in Texas, are another way to take a reflective approach.

4. Engage. Share, cooperate and collaborate in an open-source design process.

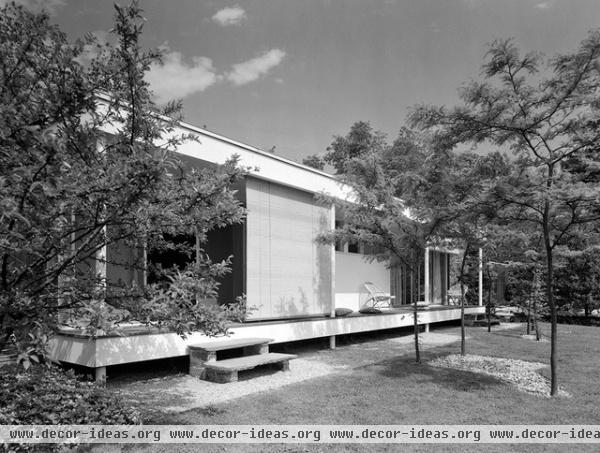

This home, by The Architects Collaborative, was designed following the group's philosophy of camaraderie instead of hierarchy. Led by Walter Gropius, the group of eight architects promoted collaboration over individualism in design to produce the best product.

Today design charettes, in which several participants meet to brainstorm solutions to an architectural problem, are another example of collaboration.

5. Participate. Make everyone an active participant in the design process.

Color consultant Debra Kling (whose work is shown here) is an advocate of this idea, and she always engages her clients in her designs. "Color consulting with my clients is always a very collaborative process," she says.

Clients who participate in designing their homes generally get more satisfying results.

6. Evolve. Look beyond current needs and circumstances to consider how good Slow Design can manifest positive change.

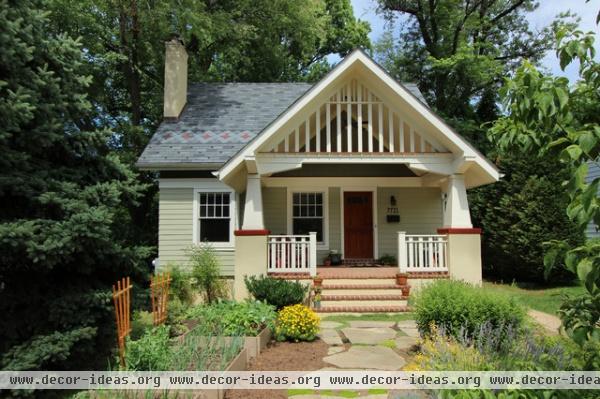

Strauss and Fuad-Luke cite architect and social designer Fritz Haeg’s Edible Estates, in which traditional lawns are replaced with productive domestic edible landscapes; the one here is a good example. Growing food instead of resource-intensive grass not only feeds families but addresses bigger issues of global food production and connects people with their environment and their communities.

On the most basic level, planting a tree, which will provide shade, shelter and possibly food many years later, is evolutionary.