Roots of Style: Château Architecture Strides Through a Century

According to a recent study by the American Institute of Architects, Biltmore is America's eighth favorite building. This château-style, or châteauesque, mansion is an indelible image of wealth from the Gilded Age. Commissioned by an heir of the Vanderbilt family around 1889, the astonishing 178,000-square-foot house with 250 rooms, situated near Asheville, North Carolina, is the largest private residence ever built in the U.S.

Its notable architect, Richard Morris Hunt, based the design upon French châteaus found in the Loire Valley. These 15th- through 17th-century country estates of the noble and royal classes, were a mix of late-Gothic and Italian Renaissance architecture that resulted in unique French Renaissance creations. Hunt's interpretation incorporates numerous elements of the original French châteaus, with the parts organized into a fantastical and stunning architectural masterpiece.

The original château style developed around 1880, and homes were built in modest numbers, mostly in the northeast, for about 30 years. The style rarely reached other areas of the country in that time. It is likely that other examples were built through the middle of the 20th century, but late-20th-century home building booms produced both extravagant and more modest examples across the country.

Viewing from left to right in this photo of Biltmore, notice the elements that define the style. Most originals had heavy masonry construction, as does Biltmore, and were clad with stone and then topped with a steeply pitched hip roof further heightened with metal cresting.

An elaborately detailed parapet-type dormer breaks the eave line, implying the attic story. Massive and detailed chimneys reach high to clear the steep and busy roof ridges. A flattened arch defines lower-level windows and arcades. The positioning and detail of ascending window forms reveal the location of the stairs.

Gothic stone tracery defines primary openings surrounded by shallow relief carvings. Spires and pinnacles extend the building into a fractal finale.

Let us return to earth and welcome this modest but whimsical French château–style abode. This little gem, not far from San Francisco, surprises with a delightful play of height and ornament that creates its identity. Compare the detailing here to Biltmore and you can understand the inspiration.

Most originals from the late 1800s were asymmetrical, like Biltmore. However, Renaissance influences likely persuaded some architects to balance the homes with symmetry, as on the main section of this house.

Château style preceded French eclectic architecture and can be differentiated through the characteristics found in Biltmore or the Renaissance classical details found in this house.

This handsome symmetrical facade holds a lovely balance of elements. Notice the segmented arched windows of the flanking elevations and the classical delineation with Roman arches in the centered entrance. Classical pilasters, a belt line and a pediment with stone relief further define the carefully detailed composition. Two types of detailed dormers and pinnacles cresting the hip peak cue the original châteauesque flavor.

Less formal than the previous example, though still carefully balanced, this newer house has the steep hip roof, detailed chimneys and cresting detail of the style. Note also that modern examples of the style are normally built of wood-framed construction, in contrast to their ancestors. The stone here is likely a veneer.

Though this house could be considered French eclectic, an attempt has been made to imply a château by the use of pinnacles and stone detailing. A belt line and broken eave also convey a château impression. Note the brick veneer, which can be found on many examples throughout the style's history.

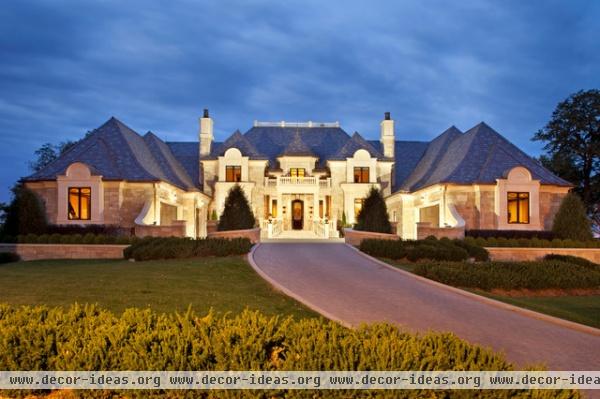

This playful composition clearly takes its inspiration from château style. The symmetrical facade combines many elements normally found in even more elaborate houses.

This formal example has a symmetrical central elevation flanked by minor extensions to the left, and generous but lower elevations to the right. Small but detailed dormers rest in the primary roof, while larger dormers break the eave line on the right. Another larger and highly detailed dormer and two small vent dormers cap the roof over the porte cochere.

Notice how this form achieves the vertical expression important to the style. Pinnacles, detailed vent dormers, quoins, a belt line, window tracery and a wrought iron railing contribute gently, in moderate amounts, to cleverly provide the château identity.

Notice the symmetrical and asymmetrical composition of this handsome home. The main body of the house is balanced exactly, yet the porte cochere and left appendage still complement the design. Note the elevation to the sides of the entrance. Asymmetrical large and small windows rhyme with the other elements.

To appreciate the flexibility of châteauesque architecture, examine this rear elevation of the same home. Generously proportioned windows elegantly open up to the private exterior spaces. This indoor-outdoor effect is not easily attained in most traditional styles.

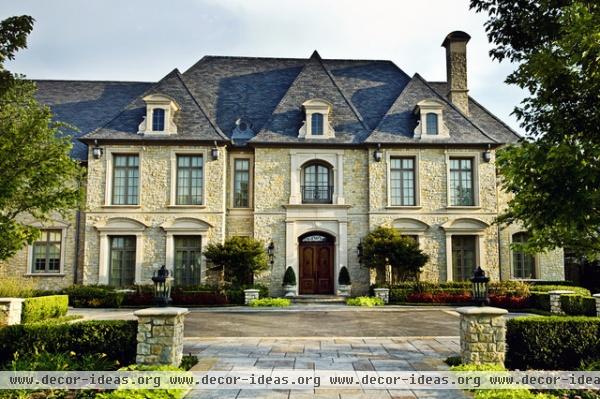

At first glance this classically detailed facade appears symmetrical. On closer inspection, however, you'll see more complex appendages and a narrow interruption to the left of the entrance, adding to the pleasure of its design. Also notice how the roof over the entrance is more steeply pitched.

This generous house relates more clearly to Biltmore in its lengthy facade and varying details. There are shed dormers and hip dormers set into the primary roof form, and hip and arched dormers that break the eave line. The entrance sits within a small inset with a detailed surround.

Original townhouse examples with many of the elements found in Biltmore survive in large Northeastern and Midwestern cities. However, this house maintains the style with slight classical detailing and a vertical emphasis.

This house achieves a country château expression through rough-faced stone and a slightly relaxed asymmetrical composition. The exquisitely detailed entrance follows the common châteauesque theme. Notice the brick chimneys with the implied quoins, a nice contrast to the stone.

Though modern design theory might eschew the imitation of styles such as châteauesque, an affection persists among the public for places with such distinct identities. Do we ever question our reinterpretation of classical architecture with the use of materials available to us, as opposed to those used by the ancients?

As history tends to repeat itself, the current attraction to modernism will likely cycle, and previously established fashions or variations of them will return. There is no right or wrong regarding this matter. Certainly other styles will emerge, but isn't it nice to have such a rich vault of design and so many choices?