Modern Materials: Copper, Architecture's Natural Beauty

http://decor-ideas.org 09/02/2013 05:50 Decor Ideas

Copper is one of the most distinctive, yet rarely used, exterior materials. Its appeal owes to the natural patina that takes hold and transforms it from orange to brown to green over about 10 years. Used most often for roofs, siding and details like gutters and downspouts, copper is actually alloyed with zinc in architectural applications. A different ratio of copper to zinc results in brass, while bronze results from copper being alloyed with aluminum, nickel, or silver. This ideabook focuses on copper and its defining green patina, both for inspiration and with some practical tips for incorporating the material.

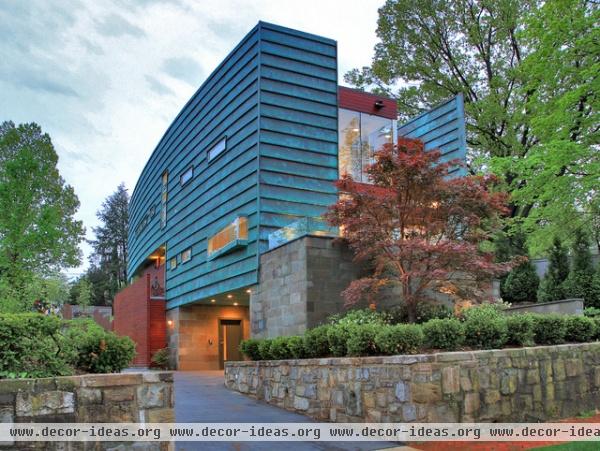

An architect with an obvious preference for copper and its patina is Travis Price, who practices in Washington, D.C. The houses he has designed in the area blend into their wooded surroundings, particularly his own, which even notches around a tree.

The fact that copper is expensive and soft yet strong means that thin sheets are ideal, and they can be shaped easily — a good combination. In another D.C. residence by Price, the gentle curve of the copper wall is not a problem, even with extremely long pieces.

The expense of copper is balanced by the fact that it has the highest recycling rate of any engineered metal. Three-quarters of copper in architectural applications is recycled, matching the rate at which it's extracted. Specifying recycled copper can reduce expense and save on the energy required to mine the material.

Copper is highly resistant to corrosion, which makes it ideal for exterior applications, but it does corrode when it comes in contact with cedar. Therefore installations like the one pictured here require a separation between the wood and the copper.

Similarly, but to a greater degree, copper corrodes other metals, such as steel, lead, aluminum, zinc and cast iron. Therefore mechanical fasteners, when needed, should be plated with copper so as not to be corroded.

As I mentioned, the green patina that forms on the surface of copper takes about 10 years to develop when left to nature. Acids and finishes can expedite the process, but an artificial patina is not an exact match to a natural one, which gives the material a subtly different appearance over time.

This house in West Virginia is similar to the previous examples, but Price turned the panels vertically, to parallel the surrounding trees.

A close-up of the facade reveals the green streaks on the copper panels, but we can also see the vertical standing seams and the way the panels overlap.

Given how copper can corrode other metals, and the fact it can be folded, soldered and welded easily, most applications have a welded rather than mechanical assembly, which also helps deals with the material's great degree of expansion.

Copper's patina can stain adjacent materials, such as stone, stucco, concrete and other light surfaces. Staining would have been a concern in this addition by Price, considering the light-colored stucco of the existing structure, but the dark shingles immediately adjacent to the copper take care of it.

This residence, designed by Wnuk Spurlock Architecture, has two volumes of prepatinated copper positioned astride a middle section that's also in copper but has yet to gain its patina.

This glance of the panels reveals the variation that can be found; what looks consistent from far away is anything but up close.

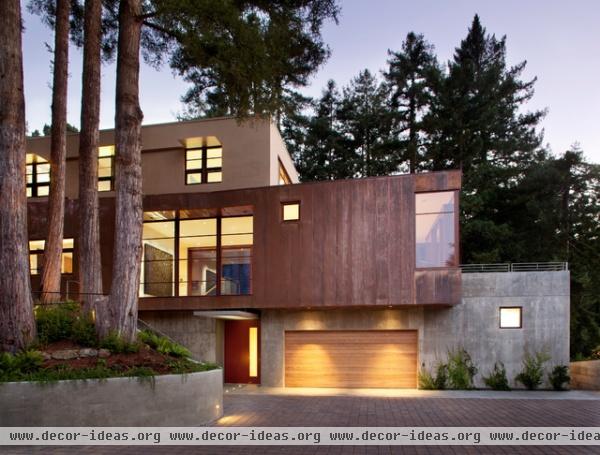

For the sake of comparison, it's good to see copper siding that has not gained its patina. This project, by CCS Architecture, has three stacked volumes, similar in size and shape but each covered in different materials. Over time the middle portion will take on a patina that will increase the house's integration into the site.

The aptly named Copper House in Sydney by Takt | Studio for Architecture exhibits the mix of colors that occurs as the material oxidizes.

Copper's patina is produced by sulfur compounds in the atmosphere, accelerated in industrial and marine environments, as well as areas with high temperatures or humidity.

This last example, by Coates Design Architects Seattle, illustrates how oxidized copper can be a design statement, bringing attention to one area, in this case the entrance. Even though the copper section is much smaller than the wood and concrete, its color grabs the most attention.

Related Articles Recommended