Strange but True Parallels Between Early Western and Old Japanese Style

If you have wabi-sabi inclinations, discovering this Japanese art of finding beauty in imperfection and impermanence feels like coming home. Most of us have been feeling the little-known philosophy’s likeness, whether we've known it or not, for most of our lives. That's because Western design shifted toward a similar wabi-sabi simplicity centuries ago.

No-frills style has permeated all the major Western design movements that still influence contemporary trends. The plain, efficient homes built by the utopian Shakers (the antithesis of the luxurious Georgian houses that were built as the United States got wealthier) and the simple, unsentimental Arts and Crafts designs of William Morris and Gustav Stickley (a reaction to Victorian repression and the Industrial Revolution’s isolation), bear the wabi-sabi mark. As do Frank Lloyd Wright’s unadorned, streamlined Prairie homes — which he called “backgrounds for the life within their walls”— and the Slow Design movement of today that urges designers to satisfy real needs over fashion.

In the next couple of weeks, I’ll take a look at Western design's wabi-sabi-like historic path. Here I'll examine how a simpler style emerged in the mid- to late 18th century and the early 1900s, when industrialization was forcing paradigm shifts that heavily influenced design.

In the mid- to late 18th century, the Shaker aesthetic — showing an ascetic pursuit of simplicity and efficiency that was free of ornament and embellishment — took hold. Westerners were drawn to the style, which was more than just a look; it was actually prescribed in the Shaker holy orders. Beadings, moldings and cornices that are merely for fancy may not be made by believers, goes the edict.

Chester Console Table - $1,228.50 » When Japanese architect Tadao Ando first visited the United States in the 1970s, he wrote home about Shaker furniture. He admired its extreme simplicity and reserve, which he said had a restraining and ordering effect on the surroundings (high praise from a man who designs the surroundings). “Technically, the furniture was rationally made with no waste of any kind,” he wrote. “In the great diversity of modern times, to experience objects representing an extreme simplification of life and form was very refreshing.”

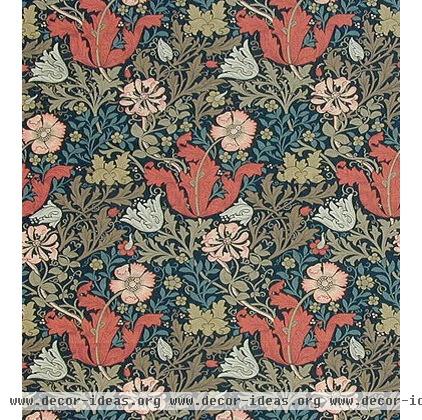

William Morris Compton Wallpaper » In 1889 housekeeping expert Emma Hewitt called excessive, cluttered Victorian decor “the American disease” and urged homemakers to “have beauty only where it is needed and appropriate.” As the telegraph, railroads and steam power accelerated everything and stuffy, brocaded Victorian parlors signaled wealth and status, William Morris began his campaign for a return to handmade quality and the death of inessential decoration. This ideal is at the root of wabi-sabi, too.

Morris — a socialist whose naturally dyed, hand-printed wallpapers (one is shown here) were ironically cherished by the robber barons — railed publicly and prolifically against what he called the “swinish luxury of the rich,” ornamental excess (“gaudy gilt furniture writhing under a sense of its own horror and ugliness,” he said) and the poverty of people who lacked creativity. “Have nothing in your home that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful,” he said — now one of the most often-repeated lines in home decorating.

Morris despised fussy, cluttered Victorian decor, and he was a vocal critic of homes being built during the era. “It is common now to hear people say of such and such a piece of country or suburb: ‘Ah! It was so beautiful a year or so ago, but it has been quite spoilt by the building,’” he wrote. “Forty years back the building would have been looked on as a vast improvement; now we have grown conscious of the hideousness we are creating, and we go on creating it.”

Morris urged his students and disciples to constantly seek beauty in life’s mundane details. “For if a man cannot find the noblest motives for his art in such simple daily things as a woman drawing water from the well or a man leaning with his scythe, he will not find them anywhere at all,” he said. “What you do love are your own men and women, your own flowers and fields, your own hills and mountains, and these are what your art should represent to you.”

Saying that a well-shaped bread loaf and a beautifully laid table were works of art as great as the day’s revered masterpieces, Morris’ successor as the Arts and Crafts leader, W.R. Lethaby, claimed that modern society was “too concerned with notions of genius and great performers to appreciate common things of life designed and executed by common people.”

His and others' appreciation for the beauty in everyday life endures today. I believe this simple, beautiful bowl of blueberries would make Lethaby and wabi-sabi followers smile.

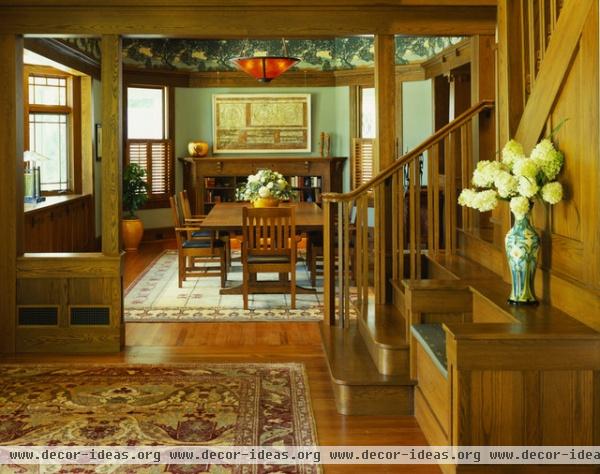

As the leading spokesman for the American Craftsman movement, which evolved from England’s Arts and Crafts movement, Gustav Stickley brought simple, solidly made furniture to the American masses at the end of the 19th century.

Stickley employed “only those forms and materials which make for simplicity, individuality, and dignity of effect,” he said. He and his family lived in a simple log cabin, of which he wrote: “First, there is the bare beauty of the logs themselves with their long lines and firm curves. Then there is the open charm felt of the structural features which are not hidden under plaster and ornament, but are clearly revealed, a charm felt in Japanese architecture.”

As this photo demonstrates, Stickley’s simple, classic furniture remains a staple in homes throughout the world.

Victorian clutter and Arts and Crafts simplicity managed to live side by side for many years, until Frank Lloyd Wright wedged his wabi-sabi-like ideas about organic architecture deep into the American psyche in the early 20th century.

Rooms should be “backgrounds for the life within their walls,” said Wright in explaining the streamlined style, with a noticeable lack of decoration and ornament, of his Prairie homes. Just to make sure no one missed this point (people rarely did), he added emphatically, “And no junk!”

More: 4 Obstacles to Decluttering — and How to Beat Them