Discover the Intriguing Possibilities of 3-D Printing for Architecture

Using 3-D printing to create something out of nothing seems like magic: Is your bathroom sink's faucet dripping at night? With the push of a button, you could have a brand-new one in minutes. Did that handle break off your silverware drawer again? No problem; just print a new one.

For architects the potential of 3-D printing is especially thrilling; its efficient use of materials, time and labor could be the way of the future. "But I think the focus here should not be whether the technology will make house building cheaper or expensive; it's really the design freedom that the technology enables designers to do," says Sophia Tang, designer at Softkill Design, a London firm that's developed an initial prototype for a 3-D printed house. Softkill is just one of many firms taking advantage of what 3-D printing has to offer and leading the way with innovative and conceptual home designs.

Take a look at these three early concepts for 3-D printed architecture: Could these be the basis of a new kind of house your grandchildren or great-grandchildren may live in?

Janjaap Ruijssenaars, principal at Dutch firm Universe Architecture, planned his latest design first, then decided that 3-D printing was the best way to bring it to life. Printing the first model with a 3-D printer allowed the team to build it from top to bottom (using a 3-D printer's layering technique) without any seams in the design. Naturally, the team wondered if they could print the house in full scale.

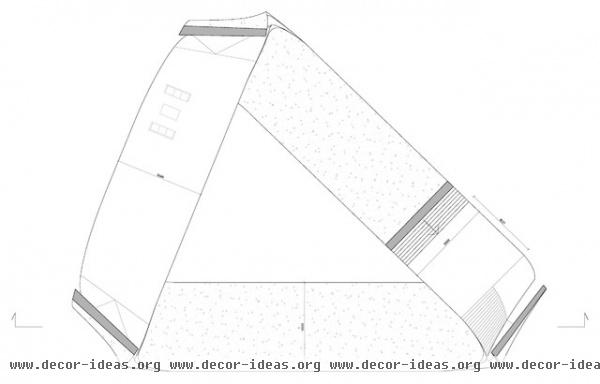

This floor plan shows the house, called the Landscape House, from above. The design started with a simple question: Can a building be like a landscape? For Ruijssenaars, the most important part of a landscape is that it has no beginning or end.

Along with artist Rinus Roelofs, Ruijssenaars designed the house in the shape of an endless Möbius strip. The house is a single loop with steps from one floor to the next, all using the same surface.

Construction of the house is scheduled to start in 2014. Ruijssenaars will print everything in these renderings that's not glass, filling the printed parts with fiber-reinforced concrete and steel for structural stability. The printer will use a mixture of sand and a binding agent to print 20- to 30-foot sections of the house from the ground up.

While this design is far from accessible right now, Ruijssenaars believes it can help link architecture to 3-D printing, eventually leading to a new construction technique.

Softkill Design's wild, spiderweb-like design takes a very different, more conceptual approach to 3-D printing. The idea is represented here, in a 3-D printed model at 1:33 scale. Made entirely out of woven 3-D printed plastic, the prototype would preserve materials and reduce labor time. The construction is based on an algorithm that imitates bone growth and deposits more material along lines of stress, using only what's necessary and efficient.

This initial design is the firm's first prototype of a 3-D house, where they experimented with different ways to combine 3-D printing and architecture.

Clearly, many logistical issues need to be addressed, so Softkill is currently working on a second version of the house that would resolve concerns about function and comfort for real life use.

After a year's worth of research on structural optimization, the Softkill team believes they've come up with a way to design cheaper buildings that use less material without sacrificing structural integrity. "In a way, the house was just a little case study for us, to see if there's any form of design or aesthetic that could be produced purely for 3-D printing," says designer Tang. "We're not interested in replicating what can be done with other existing methods."

The woven structure would almost act like a rainscreen — a separate waterproofing layer acts as the exterior cladding and interior walls to protect the structure from inclement weather. While the design could technically be printed in any material, Softkill would print the house in laser-sintered bioplastic.

Softkill says the house could be printed in 31 sections in three weeks, using the largest 3-D printer in the world. Each piece would be about 26 feet wide and 13 feet long, but lightweight enough to transport via truck. The sections would simply interlock without adhesive, reducing construction time to one day.

Designer Bryan Allen and sculptor Stephanie Smith have combined forces to take an approach similar to Softkill's: creating a brand-new construction material with 3-D printers. The final printed form of the material, pictured here, was inspired by the xylem layer of trees. "The 3-D printing process allowed us to manifest a form that would not have been possible any other way," says Allen.

This rendering shows one application: a pavilion in one of Northern California's redwood forests, to be completed in August 2013.

More: 3-D Printing Takes Furnishings in a New Direction