Design Icons: Le Corbusier, Pioneer of Modern Architecture

Le Corbusier is considered one of the three most influential architects of the 20th century (if not the most influential), usually positioned alongside Frank Lloyd Wright and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. His buildings and urban plans pointed the way for countless architects and even bureaucrats, many taking his ideas in directions (housing projects, for example) that have made his contributions questionable. In a new exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City (Le Corbusier: An Atlas of Modern Landscapes, June 15 to September 23, 2013), curator Jean-Louis Cohen reconsiders Le Corbusier's work in terms of various types of landscapes. While the exhibition can't replace some long-held notions, it does give us a new lens for thinking about the architect and his prolific output.

Born in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, in 1887 as Charles-Edouard Jeanneret — he gave himself the moniker Le Corbusier (The Crow) later — Le Corbusier opened a studio in Paris after traveling to Germany, Greece, Italy and Turkey. From the opening of his studio in 1922 to his death in 1965, Le Corbusier would realize more than 50 buildings and write more than 30 books, also tackling the design of cities.

His influence stems from his architecture, ideas and ambitions, but also important was the evolution of his architecture from International-style modernism in the 1920s and '30s to expressionistic buildings rendered in concrete in later decades. This ideabook looks at his residential projects to paint a picture of one of the 20th century's most influential architects.

If any one house comes to mind upon hearing the name Le Corbusier, it is Villa Savoye, shown here, just outside of Paris and completed in 1931. The house embodies the architect's Five Points for a New Architecture (the supports, the roof gardens, the free design of the ground plan, the horizontal window and the free design of the facade) in a form seemingly without precedent. But how did Le Corbusier arrive at this design? What happened in the three decades leading up to its realization that enabled such a substantial shift from the norm?

Like many architects before and since, Le Corbusier (seen here in Sweden a couple years after the Villa Savoye was built) was influenced by teachers and employers in his early years. These included Charles L'Eplattenier in La Chaux-de-Fonds, August Perret in Paris and Peter Behrens in Berlin.

The last two had a strong influence in particular; Perret for his expressionistic designs in concrete, and Behrens for his poetic functionalism. Of course, Le Corbusier was more than the sum of these parts, but his choice of mentors helped to give him direction.

After a year of self-education in Germany, Le Corbusier returned to La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1912, teaching and designing his first independent commission for, naturally, his parents.

The Villa Jeanneret-Perret (aka Maison Blanche) could hardly be any more different than the Villa Savoye. In fact, Le Corbusier's own monographs and other documents play down the role of this early design, even as it may have played a role in his development.

The neoclassical design departed from the traditional architecture prevalent in the area at the time, but its execution bears some of the simplicity of the modern architecture that would follow in just over a decade.

This large opening (seen in a full-scale interior at MoMA, one of four from the exhibition), in particular, presages the ribbon window of Le Corbusier's Five Points. Small openings prevailed in much of the house, but the liberation of windows from structural exterior walls would have allowed for even large openings.

The Villa Schwob, also located in his boyhood hometown, exhibits an eclectic, Oriental tendency that likewise doesn't strongly point to Le Corbusier's evolution. Still, the liberal use of volumes, surfaces and windows seems to capture an architect trying to find his way. The Fondation Le Corbusier calls it "his most accomplished work before leaving for Paris."

After his move to Paris and the setting up of his practice with cousin and longtime collaborator Pierre Jeanneret, Le Corbusier realized the first of his Purist houses: Villas La Roche-Jeanneret (1923–25); two houses, with a gallery for La Roche.

The distinct break between these houses can be found in the intellectual development that happened from writing (Le Corbusier actually put "homme de lettres," or "man of letters," on his identity card when he became a French citizen in 1930); namely, he wrote for the journal L'Esprit Nouveau and worked out his Five Points.

A two-story curved volume (shown in the previous photo and visible through the glass wall here) houses La Roche's gallery, while other parts of the Five Points can be found in the ribbon windows and the free design of the facade. Later Le Corbusier would call the double villa the first of his Four Compositions (the last was Villa Savoye).

With these compositions the architect carefully tracked his evolution, here noting the way the "inside takes its ease and pushes out to form diverse projections," as he wrote.

The full-scale room from the exhibition that displays Le Corbusier's Purist phase is the Pavilion for the Villa Church in Ville d'Avray (1927–29), in which Le Corbusier renovated a neoclassical house into a very modern one. The exhibition's interior focuses on the way the architect used the window to carefully frame the landscape, transforming it into a two-dimensional picture.

So by the time Le Corbusier received the commission for the Villa Savoye outside Paris, the idea of landscape had been explored but hardly with such a powerful site in an opening in some trees. The architect made the most of the site by lifting the living spaces above the landscape and celebrating the car in the process through a driveway that looped around the building and curved around some glass walls on the ground level.

The combination of raised living spaces and ribbon windows resulted in rooms with panoramic views of the surrounding trees. As with the Villa Church, the landscape is flattened on the glass, like an image that is selectively framed.

Recalling the window at Villa Church even more than the ribbon window is the opening cut into the wall defining part of the roof two floors above the entrance. Here we are above the treetops, and aware of this, Le Corbusier carefully framed a distant view. This was a tactic that he had done repeatedly, but at Villa Savoye, it is the culmination of a promenade architecturale through the house and other views of the landscape.

After the Villa Savoye — the fourth of his Four Compositions and the most celebrated of his houses, even in his day — Le Corbusier spent his time on large commissions, even tackling urban plans to a greater degree than any other architect before or since. In many cases the architecture and urban plans were united in idea and conception.

The Unité d'Habitation (1947–52) in Marseilles, France, is a stand-alone building, but one that embodies Le Corbusier's social goals. The large concrete building houses 337 apartments as well as a hotel and an elevated shopping "street" — both of the latter are still in use today. All of the various types of residential units are flow-through units; interlocking duplexes are arranged such that corridors happen every few floors.

One result of the interlocking duplexes is cross ventilation, otherwise difficult in multifamily housing with double-loaded corridors. It also means that all the units face toward the sea, whether with their living rooms or bedrooms. These generous views are illustrated in the fourth full-scale interior in the MoMA exhibition, pictured here.

The 1950s was a fruitful decade for Le Corbusier (and for many architects after the end of World War II), but much of his architecture bore little resemblance to the Purist buildings of the 1920s for which he is known.

If the earlier period was about the Five Points, this mature period was about the Modular (a proportional system he developed that was based on the human body with one arm upraised) and its application to projects in sometimes obscure ways.

But what really comes across in this project is the overt tactility of the brick, concrete and wood, which would have been anathema in his Purist phase.

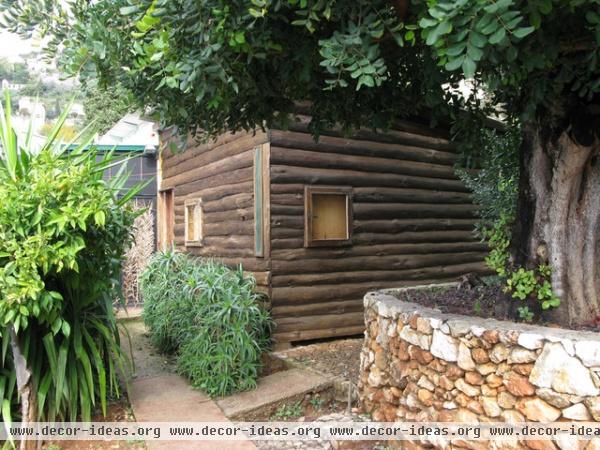

The qualities evident in Maisons Jaoul would find realization in much larger projects in France and beyond, but one of the most interesting projects carried out in the same decade is this cabin Le Corbusier built for his wife in the South of France. The unassuming one-room cabin is only 12 feet square, but as we'll see, it's all about the furniture.

In fact, Le Corbusier treated the furniture as architecture. He said, "The furniture here constitutes the first form by which the object comes into being."

Removing one wall of the Petit Cabanon for the exhibition reveals how the plywood-covered interior was zoned (following the Modular system) to work throughout the day, and how the small windows carefully frame the landscape. The window we see in the exhibition happens to frame the beach where Le Corbusier died in August 1965.

Those visiting the MoMA exhibition are confronted with the cabin and Le Corbusier's death before seeing anything else in the show, but the highly personal design prepares visitors to see the person behind the projects and ideas.

More: 10 Must-Know Modern Homes