Design Icons: Rudolph M. Schindler, Evolving Architect-Artist

Rudolph M. Schindler (1887–1953) is typically associated with Los Angeles, which makes sense, considering that most of the Austrian-born architect's output in the middle of the 20th century was in and around the metropolis. His influence on later generations of California architects is typically ascribed to the plasticity of his forms (which he focused on over function and technical aspects) and the relationship of the rooms in his houses to outdoor spaces. But he also contributed a number of ideas about collective dwelling, going beyond the single-family houses that dot the landscape.

R.M. Schindler, as he came to be known, was trained as both an engineer and an architect in Vienna. He worked for only about a year or two before he embarked for the United States to work for a firm in Chicago; he set sail the same month as the outbreak of World War I.

Even though he did not see the move as a permanent one at the time, the war and his employment by Frank Lloyd Wright a few years after the move colluded to keep Schindler in the U.S. His move to Los Angeles and marriage to the socially and politically involved Pauline Gibling at the end of the decade cemented his stay.

Over the course of his career — from his training in Vienna to his apprenticeship in Chicago and decades working in Los Angeles — Schindler moved from an architect-engineer to an architect-artist. Wright hired him due to his engineering knowledge, but in the years after Schindler set out on his own, he was charting a unique path with a distinctive style. Let's take a look at some of Schindler's projects to see the evolution of his formal and aesthetic sense and how he also went beyond that in his architecture.

Related: 10 Must-Know Modern Homes

The project that Schindler is best known for is an eponymous dwelling he built for his family and for friend and engineer Clyde Chace in 1922. The Schindler House now serves at the home of the Vienna-based MAK Center, holding exhibitions of art and architecture. We'll go into more detail on the house in a bit, but first it's worth looking at a project Schindler worked on during his tenure with Frank Lloyd Wright.

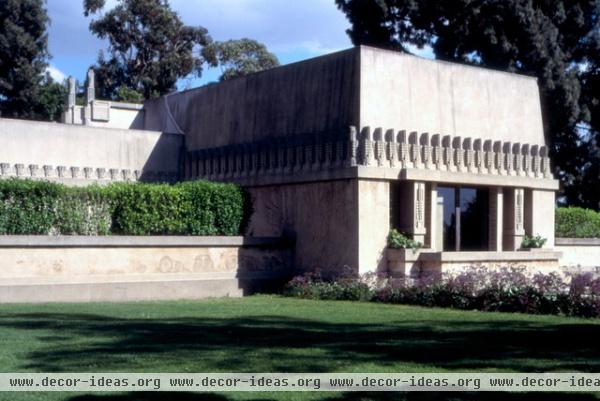

The Hollyhock House, East Hollywood. Wright started designing the Hollyhock House for Aline Barnsdall in 1918; it was completed in 1921, the year Schindler set out on his own. In that three-year period, Wright was spending most of his time in Japan, overseeing the large Imperial Hotel. Therefore Schindler and Wright's son did the drawings and oversaw the construction, respectively. Eventually Schindler took over all aspects of the project, and Barnsdall became a regular client of Schindler's after her house was completed.

As with many of Wright's projects, the cost ballooned as the project went on, and Schindler had to make changes on his own, rather than wait for Wright's approval from Japan. Schindler didn't like the heavy and sculptural nature of the design, and changed some of those aspects. Wright was not happy with the house's outcome, saying: "It had been finally completed with great difficulty ... partly because I had to leave it in amateur hands."

The Hollyhock House has previously been open for public tours, but currently it is closed indefinitely for restorations.

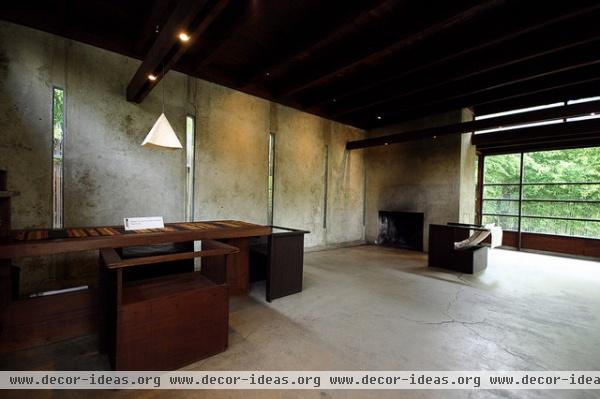

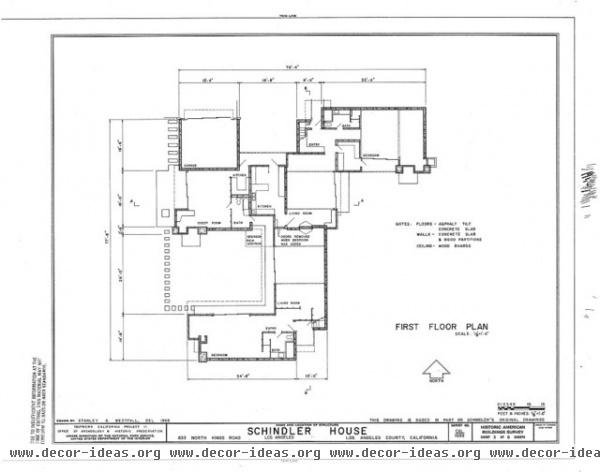

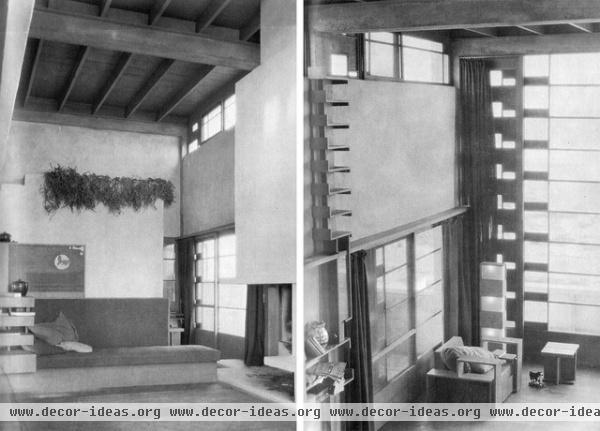

The Schindler House, West Hollywood. The house Schindler built for his family and the Chace family is unique for being a dual dwelling, but also for its construction, its floor plan and the relationship of the rooms to outdoor spaces. This view of Schindler's study (his wife had a study nearby, both overlooking the same patio) shows the technical innovation: Walls are made of tilt-up concrete panels instead of wood framing; the hybrid construction of concrete walls, concrete floors and wood roofing gives the spaces their strong atmosphere. Narrow gaps between the panels serve as windows that maintain privacy; these walls face the neighbors and the outdoor spaces of the Chace family.

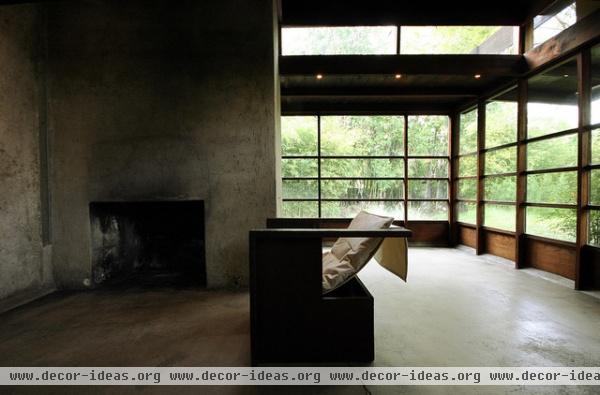

Here is another view of Schindler's library, showing the large windows and eaves overlooking the patio.

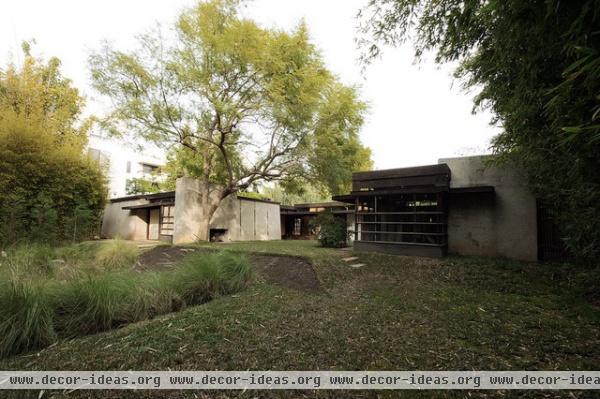

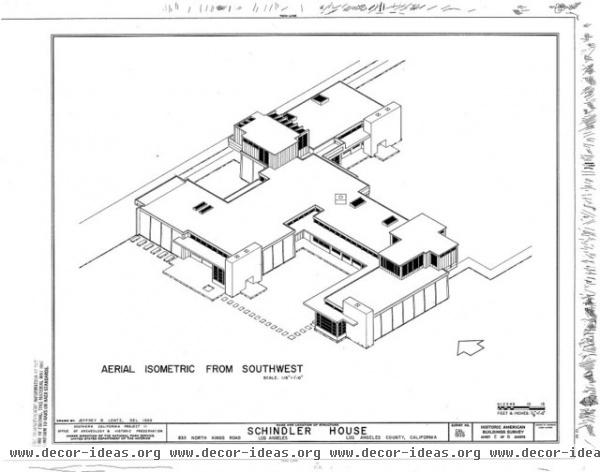

The form of the building responds to the dual-dwelling nature of the project and the creation of outdoor spaces through three L-shaped pieces. The one in the foreground served the Schindlers, the one going away from us was for the Chaces, and the one on the left contained the communal spaces (garage, kitchen, guest room).

The raised portions visible in the previous drawing, occurring at the knuckles of the Schindler and Chace volumes, serve as entrances, as hallways linking the two parts of the Ls, while also housing bathrooms and, above those, sleeping porches. The character of these spaces indicates that Schindler also was influenced by Wright's time spent in Japan.

The plan is unique not only for the way it defines indoor zones and outdoor spaces (seven distinct living spaces outside!), but also because it is completely without bedrooms. Inspired by future client Phillip Lovell's ideas on health and outdoor living, the families slept in the open in "sleeping baskets" that were lofts above the entrances. Schindler was not the only architect to embrace this idea (the Greenes incorporated sleeping porches in their Gamble House), but sleeping lofts in a communal dwelling were unique.

Pueblo Ribera Court project, La Jolla. Schindler's ideas on communal dwelling continued in the Pueblo Ribera Court project in La Jolla, near San Diego. Hired to design a dozen dwellings on some land near the Pacific Ocean, Schindler placed the bungalows in L-shaped pairs, each taking up one leg and looking out to its own patio.

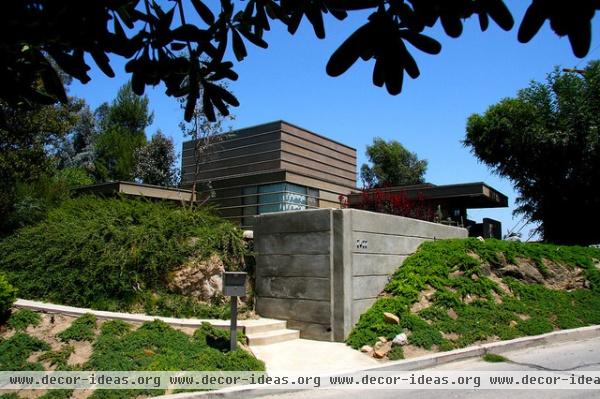

The architect also continued his stubborn focus on concrete over wood construction, designing horizontally banded walls that recalled some of Wright's houses in wood. Reportedly the concrete construction, among other things, did not work well in the salty air (deteriorating concrete and leaks were common), but the dwellings remain to this day.

An endearing aspect of the design — something that allowed the client to put up with the higher cost of concrete and anticipated technical problems — is the rooftop terraces, marked by the wood trellises. Due to Schindler's planning of the bungalows and the slope of the site, each unit has views of the Pacific.

J.E. Howe house, Los Angeles. The house for J.E. Howe in Los Angeles resembles the Pueblo Court project, but concrete enclosures were eschewed in favor of wood (concrete is still to be found in the site walls in the foreground). Even though the plan and volumes of the house point to Schindler's own style, the horizontal battens recall Wright's architecture.

Lovell Beach House, Newport Beach. Another beachfront project, also in concrete, is back in the L.A. metro area, at Newport Beach. The beach house for healthy living advocate Phillip Lovell is examined in detail in a Must-Know Modern Home ideabook, but here the focus is on Schindler's shift from architect-engineer to architect-artist. The impressive concrete frame propping the living spaces above the beach level can be seen as strictly in the realm of engineering, but their sculptural nature points to their form's being as important as their engineering qualities.

As in Schindler's own house, sleeping porches are provided in the Lovell Beach House. They were eventually enclosed; compare this photo to one taken earlier.

The plasticity of the house's interior (the articulation and treatment of the surfaces and windows) is another indication of Schindler's shift from engineering to art. The house also plays an important part in this shift, because he finally gave in to the pressure to build with wood framing after this bravado concrete structure.

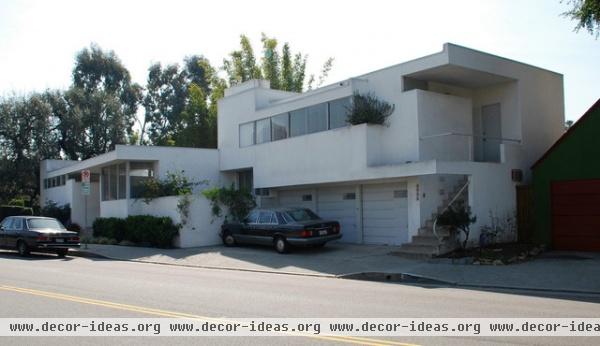

Even though Schindler's Lovell Beach House was not included in the influential 1932 "International Style" show at MoMA (friend Richard Neutra's Lovell Health House was, though), a couple years after the exhibition Schindler created designs in line with the curators' aesthetic definitions of modernism. The light wood framing gave Schindler more freedom with the volumes, and he treated their surfaces with stucco painted white. Yet, like his own house, this one is a multiple dwelling: The main house is to the left of the garage (the front door is just beyond the "no parking" sign), and a rental unit is above the garage.

Bubeshko apartments, Los Angeles. Schindler designed apartment buildings in Los Angeles for A.L. Bubeshko, realized in two phases. The sloping site and the angle at which the road cut across it meant that the apartments were stepped in both plan and section. The former is most pronounced at the garages, where each phase contains three bays. The stepped section gives each apartment a terrace, atop the ceiling of the one below it. Wright's enduring influence can be seen in the strong horizontal rooflines and the decorative caps of the walls by the garages at right.

The Droste house, Hollywood. In his definitive monograph on R.M. Schindler, David Beghard defines the time from the late 1920s to the second world war as the architect's de Stijl period. This relates his work to the Dutch art and architecture style of the same name, but the author asserts that it was a personal style that involved "the use of intersecting rather than singular volumes to establish their forms," he says. The Droste House in Hollywood is a late example of his de Stijl, where the intersection of volumes and planes is especially pronounced.

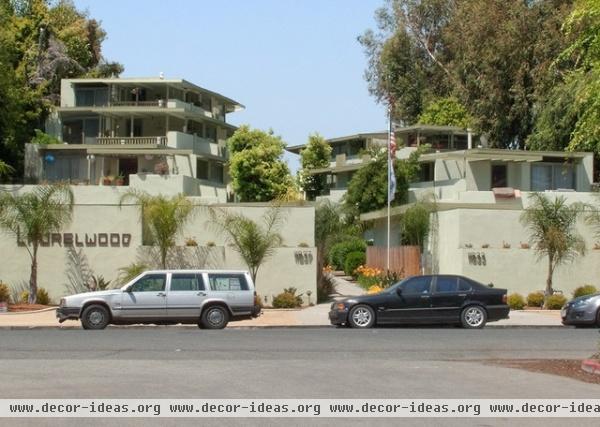

Laurelwood Apartments, Studio City. Schindler's postwar work is not as memorable as what he accomplished previously, particularly in the 1920s, but projects like the Laurelwood Apartments in Los Angeles' Studio City went well beyond the so-called "contractor-investment apartments" being built at the same time. He located auto courts in two volumes at the front of the complex (accessed from drives on the sides), and placed a walkway between the two that led to the long outdoor space between the splayed and mirrored apartment buildings.

Schindler's largest project, it utilized modular construction developed in the war and was designated a historic landmark. It received an exterior restoration in 2011, and more love of the complex can be found in the flag below the American flag, proclaiming "Schindler Design Apartments."

More: 10 Must-Know Modern Homes