Frank Lloyd Wright's Prairie Triumph Returns

Frank Lloyd Wright's Prairie-style houses are some of the most recognizable pieces of residential architecture of the 20th century. Realized mainly in the first decade of the last century, the houses have low-pitched roofs, horizontal windows, brick walls and deep overhangs as signature elements, and they simultaneously stand out from and echo the flat plains around Chicago, where Wright lived at the time.

The Robie House is often considered the Prairie masterpiece (and perhaps the last of his projects in that style, because of that distinction and Wright's desire to head in other directions), but the largest is the Darwin D. Martin House more than 500 miles away in Buffalo, New York.

The house, created and named for a president of the Larkin Company, was completed in 1904, but Wright's involvement with both the family and the company predates the house and goes well beyond it into the 1930s. This ideabook tours what is known as the Martin House Complex, comprising five Wright-designed buildings and a visitor center designed by Toshiko Mori and completed in 2009.

The complex has been undergoing restoration since 1997. Its exterior is now in pristine shape, but the interior restoration is still in progress. Nevertheless the house is well worth a visit.

Darwin D. Martin House at a Glance

Year built: 1904

Architect: Frank Lloyd Wright

Location: Buffalo, NY

Size: 15,000 square feet in the main house; 29,000 square feet in all five buildings of the complex

Visiting info: Docent-led tours are available year-round.

In just about any view of the Martin House, the elements of Wright's prairie Style are evident: the low roofs, the horizontal windows underneath the deep overhangs, the concrete planters and the brick — Roman brick (thin and long), to be precise.

Here we are looking at the southeast corner of the 15,000-square-foot main house — yes, it's that big! This corner anchors the house at the intersection of Summit Avenue and Jewett Parkway; the house is accessed via the latter. Some privacy comes from the covered porch that extends toward us in the foreground.

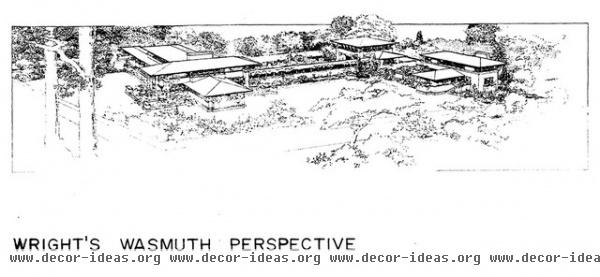

To really understand the whole project, it's best to take in one of Wright's original renderings of it. This view is looking to the northwest — the two streets can be made out in front of the house, as well as the vantage point of the previous photo, which looks at the building on the far left. From the main house on the far left, a pergola extends to a conservatory and carriage house; to the right of those pieces is the Barton House, which will be explained in the next photo.

The complex totals nearly 30,000 square feet on 2 acres. If one were to visit the site in, say, the late 1960s, one would see only the main house and the Barton House; they were the only surviving structures. As part of the restoration efforts, the pergola, conservatory and carriage house were completely reconstructed.

Before the construction of the main house and its appendages, Martin commissioned Wright to design a house for his sister Delta, married to George Barton. The 4,400-square-foot house sits on the northeast corner of the site (shown on the far right of the previous rendering). Its expression is similar to Martin's own house, but its exterior articulation and proportions make the earlier house look taller.

The four buildings that Martin would add adjacent to the Barton House give the whole site an informal symmetry, like a dumbbell running north–south.

The south elevation of the main house accentuates the lowness and horizontal nature of the design, giving it less girth than its square footage would indicate. Like most of Wright's Prairie-style houses, the entrance is hidden; a long path leads from the carport at the left to the main entrance in the middle of the plus-symbol-shape plan, aligned with the pergola beyond (scroll down to see the house's floor plan).

This fish-eye photo of the west side of the house is about the only way to grasp what is going on from the carport back to the carriage house in its entirety. A slot near the planter, just beyond the carport, is a service entrance to the main house. Past that is the pergola, a fairly formal garden, and the carriage house at the back of the site. Out of view to the left is Toshiko Mori's visitor center, which we'll see later.

The reconstructed carriage house may look slightly different in its construction (mainly, the brick has less variation than the extant main house), but overall it's an impressive reconstruction, thanks to the restoration work done on the main and Barton houses.

The accents that Wright made with the concrete planters are accompanied by decorative pieces atop the brick piers at the north end of the pergola.

Looking at the pergola from the other side (the Barton House is out of view to the right), we see the exterior of the conservatory. The skylit space, on axis with the pergola, is highlighted by a full-size cast of Nike of Samothrace.

Given the size of the site and the articulation of the buildings, the landscape took on some importance. Walter Burley Griffin worked with Wright on the landscape, making the two work together symbiotically.

One of the most important elements in the complex (and perhaps the main reason for reconstruction) is the pergola. The open-air walkway leads to the conservatory, but along the way it frames views of the landscape on both sides — the more public side on the right and the private (driveway) side on the left.

The rhythm of the space recalls Wright's design for the Larkin Company headquarters, also in Buffalo and completed two years after the Martin House. Originally a soap company, Larkin expanded into other areas and became a mail-order firm. With Wright it experimented with air conditioning in a large, central open space marked by piers reaching to skylights overhead. It was an amazing design that, unfortunately, was demolished in 1950.

As mentioned earlier, architect Toshiko Mori designed a visitor center for the Martin House Complex. Competed in 2009, the building does not try to replicate the design of Wright's house, instead opting for glass walls that open up the whole interior to the house on the east side.

The roof seems to magically float above the glass walls. It is actually an inverted hip roof (sloped on the underside) that is primarily supported on four columns in the middle of the building.

Like Wright's Prairie-style houses, the visitor center has a roof that extends well beyond the walls to provide shelter around the building and shade the glass and interior from the summer sun.

The glass and roof may not mimic Wright's design, but they reference it in a contemporary idiom and set up a frame of reference for the project across the driveway.

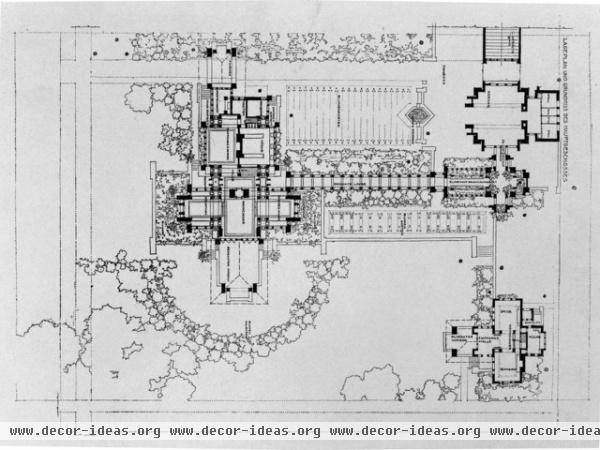

In this early plan of the complex (north is to the right, by the way), we can see the main house on the left, the pergola leading to the conservatory and carriage house, and the Barton House sitting by itself in the lower-right corner.

Also visible is the extent of Griffin's landscaping, much of it gone: the circular planting around the east-facing porch, for example, and the rows alongside the pergola, since simplified to grass.

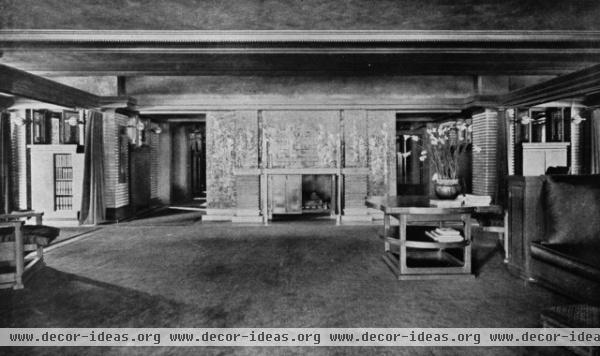

Historical photos of the interior show spaces similar to the Robie House and other Prairie-style houses — namely, low yet open spaces of brick and wood. Wright's penchant for oak has given owners of his buildings a hard time in terms of restoration, given how the wood's open grain collects dirt.

Another view of the living room points to the way Wright was able to hint at the flow of space around even the most solid of walls. Above the couch is an opening into the adjacent space, a curtain at left separates the living room and that space, and the door on the right leads to the large porch seen in the first photo.

The last phase of the Martin House's restoration is under way. It includes an upgrade of its heating, ventilation and air conditioning system; electrical and other services; the interior restoration — wood trim, plaster, paint; and exterior site work.

Original glasswork by Orlando Giannini will be reinstalled, marking the end of the $50 million restoration and bringing the house back to its state of more than a hundred years ago.

More:

What Frank Lloyd Wright's Own House Tell Us

The Birth of Modern Architecture